The Abacus, History, Uses, and Evolution in Ancient Civilizations

The term Abacus (from Greek abax; in Latin abacus; literally, table, tablet) refers to different types of objects; particularly, it refers to an instrument for performing calculations, originally widespread among the ancient Mediterranean peoples and in India. It consisted of a tablet sprinkled with dust (its name derives from the Semitic word abq, meaning sand dust) on which geometric figures were drawn, and simple numerical problems were solved.

Dust abacuses were indispensable in ancient civilizations due to the lack of a suitable number system for calculations. They were the first tool used for calculations as early as the 21st century BC in China and the Fertile Crescent, and were later used by the Phoenicians, Hebrews, Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans.

A man who performs calculations with the abacus: detail of a marble bas-relief (1st century CE - Rome, Capitoline Museums); and a reconstruction of a Roman Abacus, made by the RGZ Museum in Mainz, 1977 The original is bronze and is held by the Bibliothèque nationale de France, in Paris.

In the same geographical areas, a type of column abacus later became popular. It was made up of a rectangular board with grooves parallel to its shorter side, indicating progressively from right to left the units, tens, hundreds, up to a million. Small stones (or tokens, pebbles, buttons, rings, perforated balls, etc.) called calculi in Latin were placed in these grooves, such that each different arrangement of the stones corresponded to a number. According to Herodotus, the Egyptians used the abacus by moving the stones from right to left, while the Greeks moved them in the opposite direction. Different types of abacuses were used by the Romans. The instrument was improved by dividing the rectangle into two sections with a cut parallel to its longer side: the stones placed in the lower section always represented the units of the considered order of magnitude, while those in the upper, narrower section represented five units each.

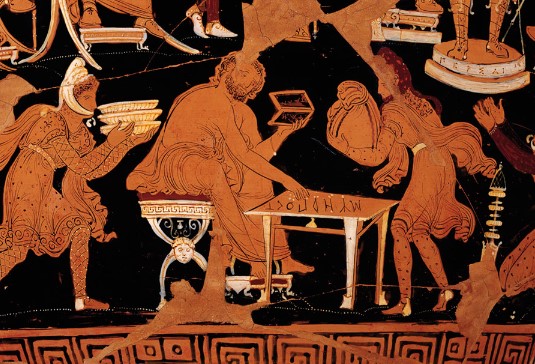

A detail of the treasurer depicted on the so-called Vase of Darius (4th century BC), who uses a token abacus - Naples, National Archaeological Museum

The token abacus consists mainly of a rectangular board that has, on one of its faces, a series of parallel grooves. Tokens are placed in these grooves according to precise conventions to represent numbers. The tokens are small disc-shaped objects with digits on their faces. Gerbert of Aurillac's abacus (later known as Pope Sylvester II) with 27 columns and a thousand tokens marked with natural numbers from 1 to 9 (lacking the symbol for zero, which was replaced by an empty space) became famous in the 11th century for enabling faster mathematical operations. The token abacus is no longer used today. The token abacus is also a type of counting board.

Statue of Leonardo Fibonacci (1170-1235) at the Monumental Cemetery, Pisa

Although still widespread in the Middle Ages, they gradually fell out of use as the Indo-Arabic decimal numeral system and the main calculation methods were introduced in the Latin West, thanks also to Fibonacci's "Liber Abaci" (1202).

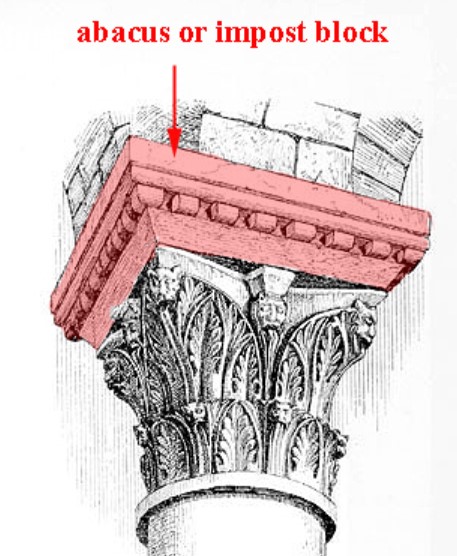

Abacus or impost block

The term abacus also referred to the upper part of the capital, consisting of a kind of square slab, varying in size in different architectural orders. It could have the shape of a cube or tablet, placed between the capital and the entablature, serving the dual purpose of expanding or reinforcing the surface area of the latter and protecting its decorated part. Among the Egyptians, it sometimes took the form of a tablet in the proto-Doric columns of the Djoser temple in Saqqara and a projecting cube in those of the Hatshepsut temple at Deir el-Bahari, although typically it was narrower than the capital (temples of Amenhotep III in Luxor, Ramses II in Karnak, Edfu, Kom Ombo). In Persian architecture, it was generally a cube placed between the two animal protomes of the capital, like the one at Susa in the Louvre. In Mycenaean architecture, it seems that an abacus tops the column at the Lion Gate in Mycenae, although it appears to be more akin to a piece of the architrave.

Funerary relief found in the necropolis of Isola Sacra (ancient Ostia, Rome). It was perhaps placed at the end of a locus and is supposed to depict a scene of work with mosaics at work, in memory of the profession of the deceased - Museo della Centrale Montemartini in Rome

In Latin writings (Vitruvius, Pliny), the term abacus also refers to the small marble or glass paste tile used to create mosaics and the mosaic designs themselves; in these meanings, the diminutive abaculus is also used.

Banquet scene with two couples of lovers and abaci, imperial age. Fresco from the House of the Lovers in Pompeii.

Among the Romans, abacus also referred to a table used like a chessboard, and to the one on which everyday dining vessels were placed; later, it was used for displaying valuable items, gold, and silverware.

Last update: October 18, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE