The Historical Origins of Abdera: A Journey from Phoenician Settlements to Modern Times

The names of towns and cities often derive from either a local geographical feature or the name of a notable individual, such as a founder or a landowner. For example, the ancient Greek city of Abdera, located in Thrace, is named after Abderus, a companion of the mythological hero Heracles (Hercules) who was killed by the horses of Diomedes. Interestingly, the name Abdera was also shared by two other cities in antiquity, one located in North Africa and the other on the Mediterranean coast of Spain.

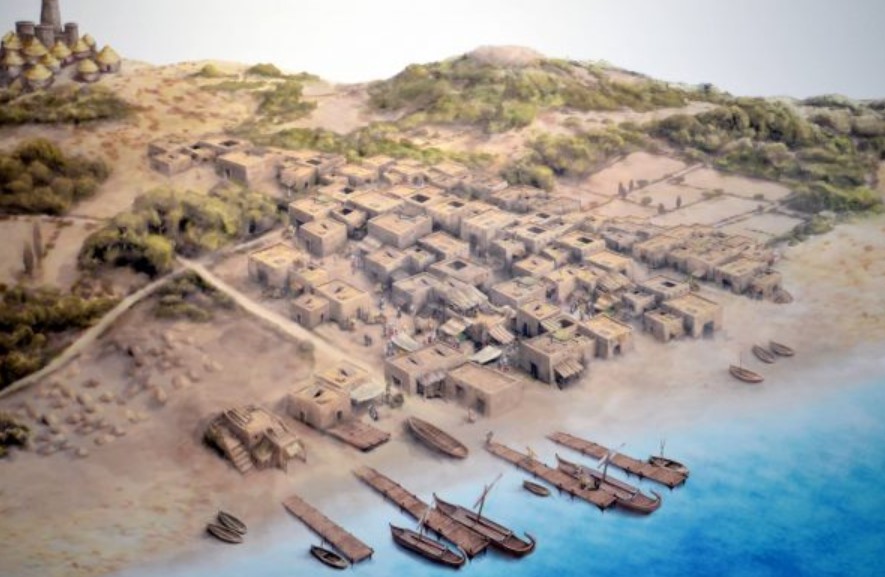

Graphical reconstruction of a Phoenician colony

Archaeological excavations confirm that the Phoenicians, a seafaring and trading civilization from the eastern Mediterranean, settled in southern Spain around 800 BCE. This settlement occurred shortly after the traditional founding of Carthage, the greatest Phoenician colony, located in what is now Tunisia. The Phoenicians' expansion westward, driven by their pursuit of new commodities and minerals, particularly precious metals, led to their interest in the mineral wealth of southern Spain.

Location of Abdera in Spain

Phoenician trade was facilitated by familial companies of shipowners and manufacturers, who were based in key Phoenician cities such as Tyre and Byblos, and they positioned their representatives abroad to manage trading operations.

After the fall of Tyre in 573 BCE and the subsequent subjugation of Phoenicia, many Phoenician colonies lost their prosperity. However, some colonies, including Abdera (or Abdrt in the Phoenician language), managed to survive and even flourish. This success was largely due to the commercial system established by Carthage, which governed much of the central and western Mediterranean. Archaeological digs have revealed the remains of a Phoenician settlement dating back to the 4th century BCE on the Montecristo hill, which overlooks the estuary of a river near modern-day Adra in the province of Almeria.

Prominent ancient authors such as Strabo, Pliny the Elder, Agrippa, and Avienus wrote about Abdera. They recorded that it was founded by Phoenician sailors during the second half of the 8th century BCE on a hill in what is now Adra, between Malaca (modern-day Malaga) and Carthago Nova (modern-day Cartagena).

Bronze coin (2nd century BCE) with Tetrastyle temple with crayfish within the central columns / Two tunny fish swimming left, Punic legend BDRT between them.

The Phoenician name Abdrt has been found on ancient coins, which also depicted tunas, while the Greeks referred to the city as Abdera. The city grew considerably due to its main economic activities, including fishing and the production of salted fish, which were vital to its prosperity.

By the first half of the 4th century BCE, Abdera had become a key trading outpost for Carthage. Following a period of decline, the Romans took control of the Iberian Peninsula in 206 BCE. Under Emperor Tiberius, Abdera was elevated to the status of a Roman colony, becoming one of the most important cities in the Roman province of Hispania Baetica. Even Roman coins from Abdera continued to feature tunas, symbolizing the city’s enduring connection to the fishing industry.

Bronze coin with head of Tiberius on the obverse and the temple of Melquarth/Hercules with two columns shaped like tuna fish on the reverse. Legend reads ABDERA in Latin and 'BDRT in Punic - TI CAESAR DIVI AVG F AVGVSTVS

The prominence of tuna on the city's coinage highlights the central role that the fish played in Abdera’s economy. Strabo, writing in the 1st century BCE, noted that the Phoenicians were expert fishermen who sailed beyond the Pillars of Hercules (modern-day Strait of Gibraltar) in search of tuna stocks. These fish were then processed in Cádiz, another important Phoenician settlement, where coins depicting tuna have also been discovered.

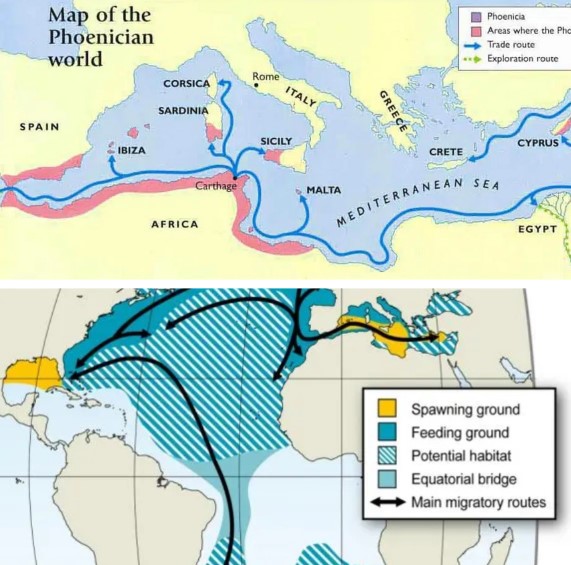

Above, map of the phoenician trade routes, and below, migratory routes (black arrows) of bluefin to spawning sites (yellow zones). In blue zones the tunas go looking for food and stop feeding during spawning

The Phoenicians were well aware of these migratory routes and followed the tuna across the seas, using the fish as a guide for their maritime expansion. This westward journey eventually led them to cross the Pillars of Hercules, effectively linking the Mediterranean and Atlantic regions into a unified cultural and economic continuum.

Strabo's account offers valuable insight into the existence of a thriving tuna fishing and trading industry. The Phoenicians employed specialized fishing techniques to catch large quantities of tuna, and they had developed methods for preserving the fish in salt, which allowed them to trade it over long distances. Some scholars suggest that the Phoenicians may have even developed early forms of the tonnara, an elaborate system of nets used to trap tuna, which continued to be used in Mediterranean fisheries for centuries.

The trap (tonnara) is a complex arrangement of nets used specifically for catching bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus), a species that can grow up to three meters in length and weigh up to 400 kilograms. The Phoenician technique of slaughter (mattanza) — , an ancient Phoenician method of trapping and killing tuna — was a key component of this ancient fishing tradition. Aristophanes, writing in the 5th century BCE, describes how a lookout would position themselves on the highest coastal ridge to spot incoming tuna schools, which would then be guided into the nets by the sea currents.

In the classical world, the nutritional and even therapeutic qualities of tuna were widely recognized. Tuna was one of the most valuable natural resources for Mediterranean populations, and the fish’s economic importance was second only to its role as a dietary staple. The bluefin tuna, in particular, was highly prized for its rich, flavorful meat. It was often referred to as the "sea pig" due to its large size and abundance. For centuries, this species provided food, jobs, and income for fishermen, shipbuilders, and those involved in the processing of tuna meat throughout the Mediterranean basin, which the Romans called Mare Nostrum —“our sea.”

A submerged mosaic in Baia: the "Fish Mosaic" (3rd century CE), whose best preserved portion shows in the foreground a tuna and perhaps an eagle during a slaughter - Archaeological Park of Baia Sommersa, Bacoli, Naples

The decline of Abdera (Adra) began with the barbarian invasions that swept through Andalusia. Documents from the Council of Seville indicate that Abdera had a bishop in the 6th century, suggesting that the city was still of considerable importance at that time. However, it frequently faced attacks from Berber pirates who plagued the Mediterranean. To defend itself, the city had to build walls and towers, which were repeatedly modified and strengthened over time. Abdera eventually came under Arab rule and became part of the Emirate of Almeria. In the 11th century, faced with relentless attacks from Berber pirates, the population retreated from the coast and settled further inland.

Abdera’s fortunes shifted again when it came under the control of the Kingdom of Castile. In 1505, Joanna of Castile ordered the construction of towers to protect the city from both Berber piracy and the local Moorish population, which had settled in the nearby Alpujarra region. From the 16th century onwards, and particularly in the 17th century, Abdera’s economy revived thanks to the introduction of sugar cane cultivation. This led to the city becoming a key port for sugar exports to Genoa and other Mediterranean cities, spurring population growth.

In 1839, the city walls were demolished to allow for urban expansion, although some remains of these fortifications can still be seen today. Even in the modern era, the economy of Adra (the current name for Abdera) remains tied to its ancient roots. The town’s modest port supports a fishing industry, and there are several small to medium-sized industrial settlements in the area. Tourism also contributes to the local economy, as does agriculture in the surrounding plains, where exotic fruits like pineapples and avocados are grown.

Last update: October 23, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE