Abella, An Ancient Gateway and Its Enduring Legacy in Roman and Pre-Roman Italy

Abella, now known as Avella, was an ancient settlement strategically located along a natural route connecting the coastal regions of Campania to the Irpinia inland. This location provided a pivotal position for trade, communication, and defense. The etymology of "Avella" is uncertain and steeped in local lore and geographic features. According to the Roman historian Justin, the city’s Chalcidian settlers called it abel, meaning "grassy field suitable for grazing," a name that reflects the area’s fertile plains, shaped by volcanic soil. Another theory suggests that the name originates from the Latin avello, meaning "to uproot with force," referencing the strong local winds known to unearth trees and even uncover buildings.

Abella’s history, however, remains partially hidden. Centuries of pillaging and destruction forced its residents to flee into the nearby mountains for extended periods, making archeological evidence scarce and limiting what can be definitively known about the city’s past.

The abel (grassy field suitable for grazing) territory around Abella

Prehistoric Roots and Early Settlement

Human presence in Abella traces back to the Upper Paleolithic period, with the first settled community believed to have arisen in the Apennine phase. Artefacts from the transition between the Copper and Bronze Ages (circa 2000 BCE) have been discovered, alongside Iron Age relics (7th–6th centuries BCE), which include intricately decorated black-glazed pottery and metallic vessels. These finds came primarily from burial grounds near the Clanio River.

Vases dating from the 8th century BCE

Avella was originally a settlement of the Osco people (in Greek Oskoi), an ancient Italic population of pre-Roman Campania; later it underwent domination, first by the Etruscan population, then by the Samnitesc one.

Around 700 BCE, the Greek colonization of Campania’s coast marked a new chapter in Abella’s history, as the city became a central point for exchange among Greek, Etruscan settled in Capua, and Italic cultures. According to Servius, the city was mythically founded by King Muranus, who named it Moera, though both the founder and the name remain largely legend.

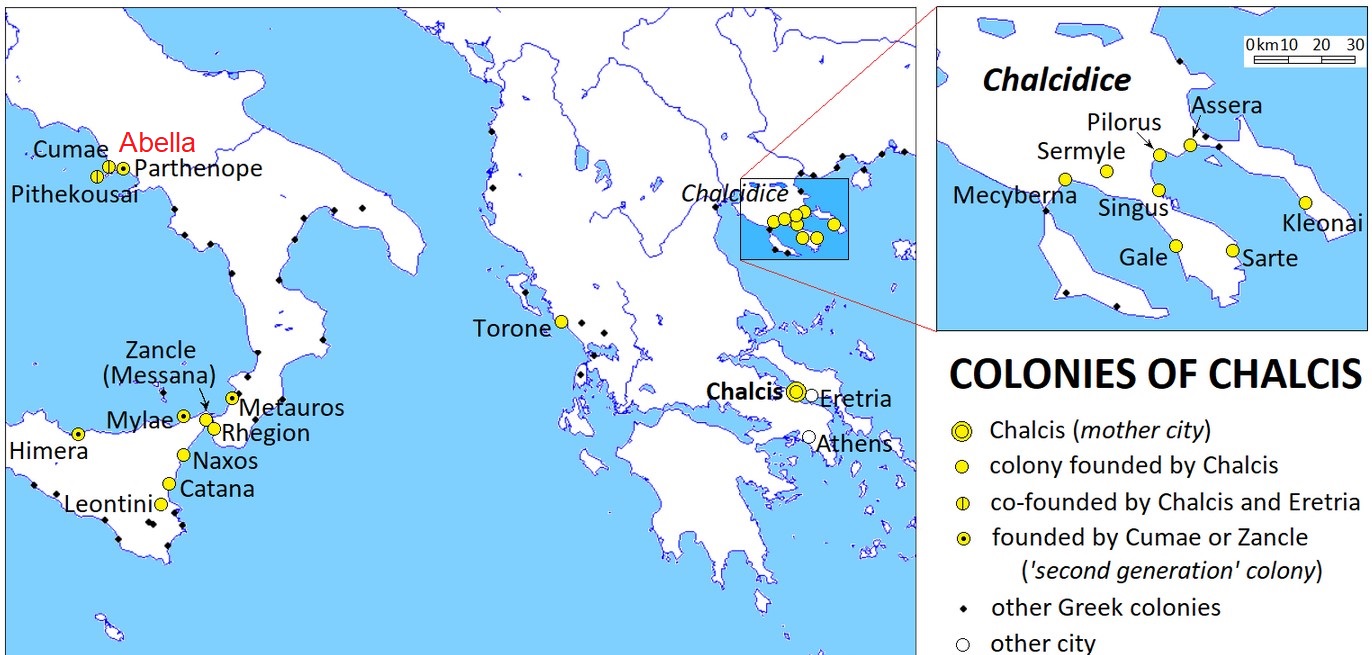

Colonies of Chalcis

Another account attributes Abella’s founding to Greek colonists from Chalcis, though archeological evidence for this remains limited.

The Chalcidian were Ionian people who colonized the homonymous Greek peninsula, especially in the 7th century BCE, and areas of the Mediterranean Sea. Between the 8th and 7th centuries BCE in peninsular and insular Italy alone, 8 cities were founded including Kyme (Cuma), and some of them became important polis of Magna Graecia. In Italy, they forged strong commercial and cultural ties with the Etruscans, who used as their alphabet that Chaldean of Cuma, from which that Latin derives. In fact, the Etruscans did not have their own writing form, at least until they had contact with the Greek settlers in Italy: they began to use a version of the Euboic-Chaldean Greek alphabet, precisely that of the Cumans and Ischian.

The city of Abella predates Rome’s founding in 753 BCE, having already been described as a populous and war-ready city by that time.

Early Greek and Etruscan Influence

Evidence from the early 7th century BCE indicates Abella’s increasing trade and cultural exchange with nearby regions. Artefacts from this period include a geometric-style oinochoe from Cuma, a decorative askos from Daunia (present-day Foggia), and vases from Caudium, Suessula, and Pithekoussai (Ischia). These objects reflect the city’s integration into a broader network of Italic and Mediterranean civilizations.

The later Orientalizing period (circa 650–545 BCE) saw an expansion of burial grounds on both sides of the city, though the city’s residential areas remain largely unexplored. Finds from these tombs demonstrate the diverse cultural influences shaping Abella, as they include artifacts from Greek, Italic, and Oriental origins.

Campania Felix and Abella

The Roman Era and Abella’s Civic Identity

In 399 BCE, Abella allied itself with Rome, becoming a civitas foederata that retained its internal governance through an oligarchic senate allied to Rome. Positioned within Campania Felix, an agriculturally rich region, Abella was less influential than neighboring Nola but remained a significant medium-sized Campanian center.

Historically under Samnite rule, Abella followed Nola’s political trajectory, receiving an oligarchic constitution from Roman general Marcus Claudius Marcellus in 216 BCE.

Abella's architectural legacy includes substantial buildings such as a theater, an amphitheater, an aqueduct, and a basilica. East and west of the city, tombs spanning from the Iron Age to the Roman period were discovered, attesting to the city’s longevity and continual use as a burial site.

Roman tombs of Avella. Monumental necropolis of locality Casale

East and west of the city are tombs dating from the Iron Age to the Roman period. The necropolis developed between the late Hellenistic and the first imperial age along an extra-urban road axis that, leaving the ancient city of Abella, led west towards the plain of Campania.

A statue base with a relief of Abella’s Roman amphitheater , the Antonine era - Avella’s Ducal Palace square

A depiction of Abella’s Roman amphitheater, whose ruins remain today, appears on a statue base from the Antonine era and is now displayed in Avella’s Ducal Palace square.

Abella’s Roman amphitheater constructed in opus reticulatum (stonework)

The amphitheater was constructed in opus reticulatum (stonework) where the houses of the Samnitesc period were destroyed during the war between Marius and Sulla (1st century BCE), that is immediately after the transformation of Abella into a Roman colony.

Built at the eastern end of the Decumanus Maximus, it was supported partly by the walls of the ancient city, partly by a natural slope and partly by large vaulted buildings. Its most obvious atypical feature was the fact that it had no underground and tunnels, as opposed to, for example, the Colosseum or the nearest Flavian amphitheatre at Pozzuoli. It can be considered, without doubt, one of the oldest in Campania and very similar in size to that of Pompeii.

Among the most important findings in the urban area are reported:

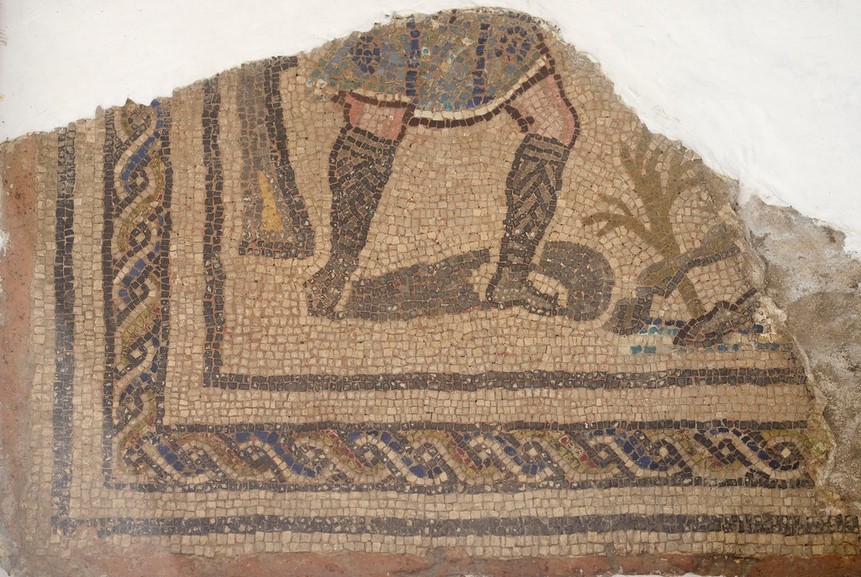

- The mosaic depicting the killing of Laius by Oedipus, found near the current Corso Vittorio Emanuele, now preserved and visible at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

- An emblema (or polychrome figurative mosaic) dating 3rd-4th century BCE. It was a highly refined genre of mosaic popular in the Roman world. These “framed mosaics” were crafted with exceptionally small tiles, making them intricate and valuable pieces. Not only were these mosaics treasured for the minute size of the tiles, but also for the wide range of colors and subtle stone shades that made up the image.

These emblemata were luxury items, often original creations or reproductions of famous paintings, and their relatively small size made them easy to transport. In fact, it is said that Caesar himself enjoyed decorating his tent with these mosaics during his military campaigns.

In antiquity, mosaics were typically made using the direct method, where each tile was placed directly into a layer of plaster over a pre-drawn guide. However, due to the meticulous craftsmanship and complexity of the emblemata, they were often assembled in a workshop on a wooden panel. Once completed, the mosaic was set into the floor, and this separate preparation process made it possible to transport them as well.

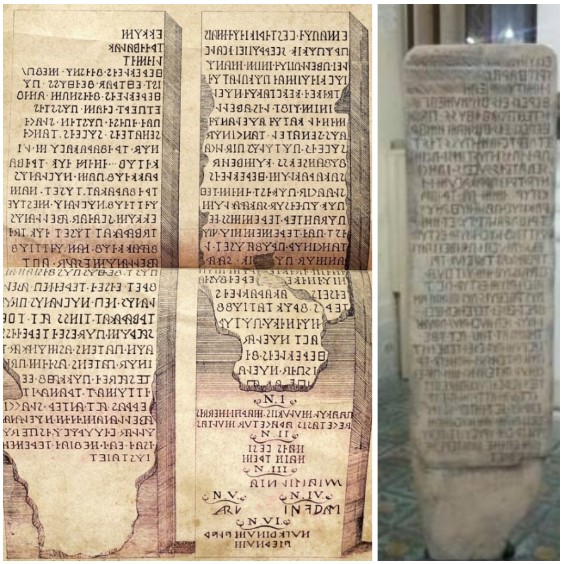

The emblema fragment on display, likely originating from Avella and part of the Zigarelli collection, is thought to depict a hunting scene. This fragment exemplifies the sophistication and artistry associated with Roman emblemata and serves as a testament to their role in luxury decoration and their cultural portability across the Roman Empire. - An Oscan epigraph, found in the area of the Santissimo, which documents the intensification of public construction, in the second half of the II century BCE. by the magistrate Maio Vestirikio: it is the same character that appears mentioned in another epigraphic document, the Cippus Abellanus.

- The Cippus Abellanus, a stone tablet dating probably 120-110 BCE, is a tombstone found in 1685 among the ruins of the Castle of Avella and kept at the Episcopal Seminary of Nola. It is a large block of sandstone bearing, engraved, the text written in Oscan language of a treaty concluded between two meddix (Samnites magistrates) of Nola and Avella on the common use of the areas surrounding the Temple of Hercules, placed at the border between the two cities. It is considered an important document for the study of Oscan.

m)a) ís.vestiri. m)a) i.

sta.prupuk.sv

er.kv.te) rem.

Maio Vest(i)ricio, (son of) Mai(o) (,)

Is (... or?) (,) prupuk(id) (,) sverrone

(,) quaestor (the police commissioner), made the confinement (scil., placed the cippes).

Cippus Abellanus

Avella, Paenzano. Figurines of Hercules

During the Social War (91–89 BCE), when Italian cities sought civil rights, Abella remained steadfastly loyal to Rome. This loyalty was rewarded with the status of Municipium under Emperor Vespasian, and his lands were distributed to the veterans. The Municipium granted the city certain privileges, although political rights remained limited and military and economic obligations high.

By 73 BCE, Abella had become a Roman colony, as evidenced by the territorial centuriation (land division) expanding from nearby Nola. The Samnites who still occupied Nola retaliated against this allegiance to Rome, ravaging Abella and its territory after Sulla’s withdrawal from Campania in 87 BCE.

The Samnites (or Sabelli) were an ancient Italic population inhabiting the Sannio and adjacent regions in southern Italy between the 7th-6th century BCE and the 1st century CE.

![Fresco of a Samnite tomb [Weege Tomb 30] found in Nola showing the return of Samnite warriors from battle - National Archaeological Museum of Naples (MANN)](../news/216.jpg)

Fresco of a Samnite tomb [Weege Tomb 30] found in Nola showing the return of Samnite warriors from battle - National Archaeological Museum of Naples (MANN)

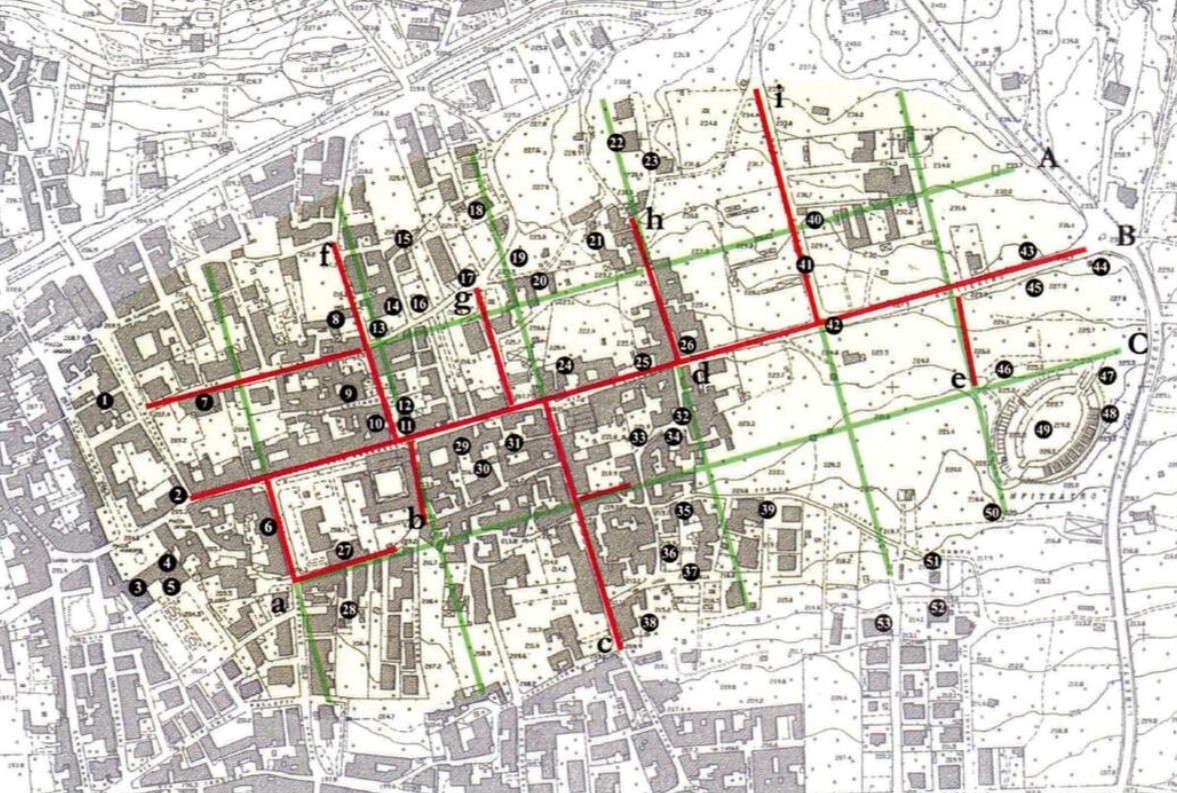

In the Roman era, Abella underwent its first formal urban planning. The city of that time had a rather rounded shape, was enclosed by walls and equipped with six gates. The eastern part of these walls has survived near the amphitheatre. Inside, the urban area was divided into four sectors by the intersection of two orthogonal roads while the neighborhoods, so identified, were in turn divided according to the typical eponymous chess board, articulated in cardines (hinges), in north-south direction, and decumani, in east-west. The old route, thus outlined, remained readable in time as it continued to constitute the road scheme around which the rest of the country was structured, excluding medieval age. In particular, the current Corso Vittorio Emanuele, oriented east-west, corresponds to what was the ancient Decumanus Maximus.

Map of ancient and modern Abella and Decumanus Maximus

Cultural Legacy and Literary Mentions

Abella’s fertile lands inspired admiration from ancient authors. Virgil famously dubbed it Malifera Abella ("Abella, land of apples"), referencing its abundant fruit and agricultural productivity. In the Aeneid, Virgil also noted Abella’s alliance with Turnus against Aeneas, highlighting the city’s historical significance. Other writers, including Silius Italicus, Strabo, and Livy, celebrated its produce, especially hazelnuts, which contributed to Abella’s renown.

Abella's Castle

Decline and Barbarian Invasions

Following the fall of the Roman Empire, Abella faced devastation during the Visigothic invasion led by Alaric, followed by attacks from the Vandals under Genseric and the Alans. These repeated invasions forced the population into the surrounding mountains, leading to Abella’s gradual decline. The Longobards of Benevento took control in the 6th century, resisting Saracen invasions in 883–884 and subduing Byzantine forces in 887. The city suffered further under Hungarian raids in 937, leaving Abella largely abandoned.

Only with the arrival of the Normans did Abella’s population resettle, sparking a new era of stability and development.

Last update: October 26, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE