Absentia in Ancient Rome: The Legal, Political, and Social Implications of Governing in Absence

Absentia, a Latin term meaning "in absence," was commonly used in Roman law, government, and administrative contexts to indicate a person's absence from a location where they were typically expected.

This concept played a significant role in shaping policies and procedures in the Roman Republic and Empire, especially in cases where high-ranking officials or military leaders needed to maintain authority or govern without being physically present. Additionally, the principle of absentia affected religious and social customs.

Men in clothes, perhaps senators (detail). Relief, marble, III CE, Sarcophagus from Acilia (Rome) - National Museum of Rome, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome.

Absentia in Roman Law and Governance

In the Roman Republic, the concept of absentia was flexible and allowed for unique political maneuvers. One example occurred in 217 BCE when a senatus consultum allowed certain absent individuals, typically those engaged in military duties, to be elected to public office despite their absence. However, a change occurred in 62 BCE, requiring that candidates appear in person, reinforcing the importance of physical presence in the electoral process. This legal standard was briefly relaxed in 52 BCE with Pompey's enactment of the lex de magistratibus, allowing Julius Caesar to run for consul in absentia, enabling him to pursue political power without returning to Rome.

The Younger Pliny Reproved, colorized copperplate print by Thomas Burke (1749–1815) after Angelica Kauffman. The Latin writer Plinius the Younger (c.62 - c. 114 CE), son of L. Cecilio Cilone and of Plinia, sister of Pliny the Elder, was legatus pro praetore in Bitinia in 111 and 112.n

Military Representation: The Role of the Legatus Pro Praetore

The Roman military and administrative systems relied on deputies who governed on behalf of absent leaders, a practice exemplified by the legatus pro praetore or legatus. These appointed officials represented the authority of a Roman consul when the latter was absent, typically during wartime or in distant provinces. For instance, Julius Caesar had multiple legati and a quaestor overseeing his legions. The legatus not only commanded military units but also held diplomatic responsibilities, which were crucial for conveying messages and negotiating between armies or leaders. This arrangement ensured continuity in governance and decision-making despite the physical absence of the primary leader.

Case Study

Flamines, Ara Pacis, west side 2 in Rome, Italy.

In ancient Roman religion, the flamen Dialis was the high priest of Jupiter. The term Dialis is related to Diespiter, an Old Latin form of the name Jupiter. There were 15 flamines, of whom three were flamines maiores, serving the three gods of the Archaic Triad. According to tradition the flamines were forbidden to touch metal, ride a horse, or see a corpse. The Flamen Dialis was officially ranked second in the ranking of the highest Roman priests (ordo sacerdotum), behind only the rex sacrorum and before other flamines maiores (Flamen Martialis, Flamen Quirinalis) and pontifex maximus. The office of Flamen Dialis, and the offices of the other flamines maiores, were traditionally said to have been created by Numa Pompilius, second king of Rome, although Numa himself performed many of the rites of the Flamen Dialis.

The Tragic Story of Flamen Dialis L. Cornelius Merula

A vivid case of absentia's implications in Roman political and religious life is the story of Flamen Dialis Lucius Cornelius Merula. During the turbulent years of conflict between the factions of Marius and Sulla, Merula was appointed consul in 87 BCE in the absence of Cinna, then in exile. However, upon Cinna's return, Merula faced accusations of murder, and rather than awaiting the inevitable condemnation, he committed suicide in the Temple of Jupiter. This case illustrates the risks and religious conflicts that arose when individuals tried to navigate both political duties and sacred obligations, especially in times of civil strife. The flaminatus, or priestly office, remained unfilled for seventy years, signifying the deep impact of Merula’s tragic fate on religious practices.

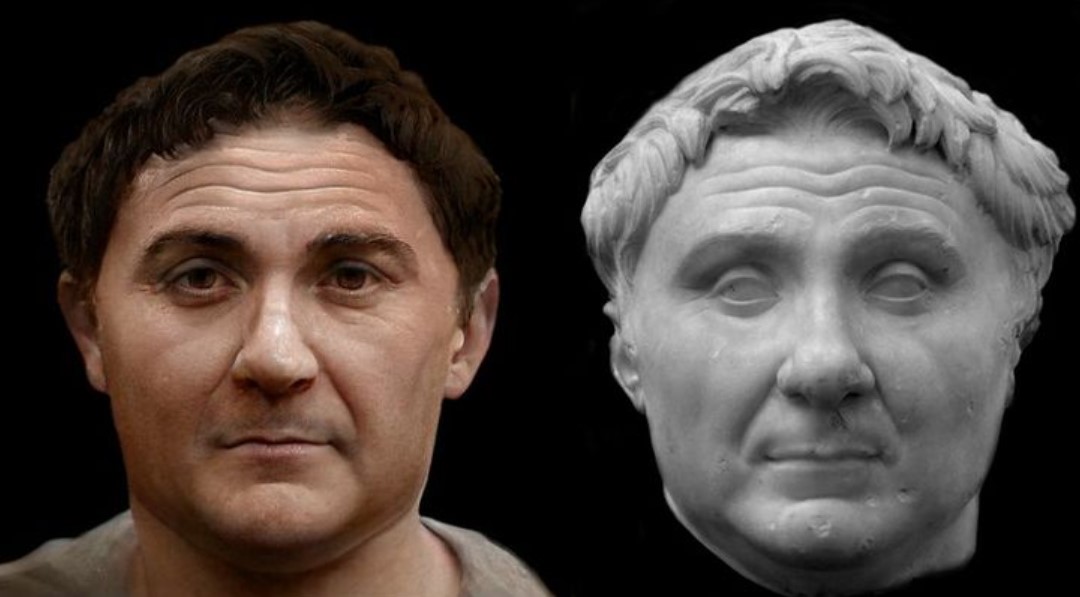

Pompey, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (106-48 BCE)

Pompey’s Governance of Spain from Rome

Absentia also affected Roman provincial governance, as seen with Pompey’s administration of Spain. Though Rome was far from Spain, Pompey managed the province without leaving Rome, using a network of deputies and trusted individuals. This practice illustrated the flexibility and political reach that absentia afforded high-ranking Romans, allowing them to control distant territories without physically relocating. The Triumvirate formed by Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus in 59 BCE was a pivotal arrangement, as it allowed the three leaders to expand their influence across regions, circumventing traditional political limitations.

The renewal of the Triumvirate's power-sharing agreement at Lucca in 56 BCE further solidified Pompey's and Crassus' ambitions. Caesar was granted an extended proconsulship in Gaul, while Crassus took control over Syria. Despite this arrangement’s effectiveness in consolidating power, it showcased the increasing corruption in the Roman Republic, where a few elite figures could dominate the state, exploiting absentia for political gain.

Antonia Minor - National Archaeological Museum, Venice

The Influential Role of Antonia Minor and the Tabula Siarensis

Antonia Minor (36 BCE - 37 CE), a prominent figure in early imperial Rome, embodies the societal dimension of absentia. Daughter of Mark Antony and Octavia (Augustus' sister), Antonia married Drusus, a high-ranking political figure. Her loyalty to Augustus’ policies and her decision to remain single after Drusus’ death solidified her status as a univira (a woman married only once), which underscored her moral and social standing. Antonia's family connections linked her closely with the Julio-Claudian dynasty, influencing imperial politics even in her absence from the public sphere.

Her son, Germanicus, reached high political ranks under Tiberius, but his mysterious death during a mission in the East left a controversial legacy. Roman society mourned Germanicus, and Antonia’s involvement in the ensuing commemorative events was confirmed by the Tabula Siarensis, a bronze inscription found in Spain. This document reveals that the Senate officially invited Antonia to participate in her son’s posthumous honors, underscoring the role of absent figures in Roman commemorative practices. Tacitus, however, suggests that Antonia's role was minimized, reflecting political biases in historical accounts and the complexities of Roman mourning rituals.

Last update: November 1, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE