Acacius of Constantinople, the bishop who defied the power of the papacy

Acacius of Constantinople, an influential Byzantine bishop of the 5th century, held the position of Patriarch of Constantinople from 471 until his death in 489. Known primarily for initiating the Acacian Schism, Acacius played a significant role in shaping the theological and political landscape of the Eastern Church. His career reflects both his ambition and his ability to maneuver within the complex dynamics of the Byzantine Empire, particularly in his efforts to assert Constantinople’s autonomy from Rome.

A faithful reconstruction of Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire

Historical records first refer to Acacius as an orphanotrophos, a title that designated him as a caretaker of orphans within the Church of Constantinople. This position granted him considerable standing within the Church hierarchy, and he became known for his refined manners, generosity, eloquence, and theological knowledge.

His virtues led to his election as Patriarch following the death of Gennadius in 471. For the first few years of his episcopate, there were no notable conflicts or significant events. However, the ascension of Emperor Basiliscus in 475 would soon bring Acacius to the forefront of an intense religious controversy.

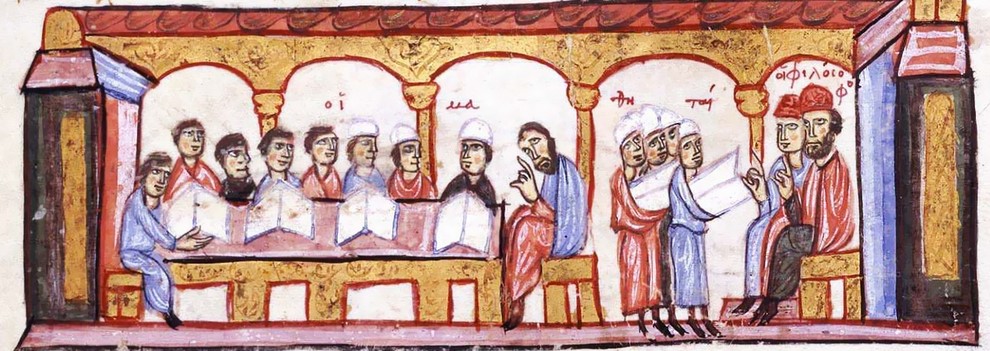

Pandidakterion was a school founded in 425 by Emperor Theodosius II in the Capitolium of Constantinople with 31 chairs: 10 each for Greek and Latin grammar; two for law; one for philosophy; and eight chairs for rhetoric, with five taught in Greek and three in Latin. - Illumination from Skylitzes codex, 13th-14th centuries. Image No. 0024558 Credit: The Granger Collection, NYC

In 475, Basiliscus became the Eastern Roman Emperor after a revolt forced Emperor Zeno to flee Constantinople. Basiliscus, although initially successful, was a ruler prone to nepotism, which alienated the clergy, populace, and military. Seeking support from the Monophysite faction, Basiliscus promoted the doctrine of Monophysitism, which asserted that Christ had a single, divine nature rather than two distinct natures, one human and one divine. Monophysitism, drawing from Greek (monos for "one" and physis for "nature"), argued that Christ’s human nature was absorbed by his divine nature, a view conflicting with established orthodoxy.

On April 9, 475, Basiliscus issued an encyclical (Enkyklikon) calling on all bishops to reject the Council of Chalcedon, held in 451 to settle disputes regarding the nature of Christ. While many Eastern bishops endorsed the decree, Acacius initially showed favor towards it. However, upon receiving a letter of warning from Pope Simplicius, Acacius re-evaluated his stance and decided to oppose the Monophysite decree actively. This reversal won Acacius widespread support among the monastic communities and the people of Constantinople. Pope Simplicius, who had been concerned about the encyclical’s implications, praised Acacius for his commitment to orthodoxy.

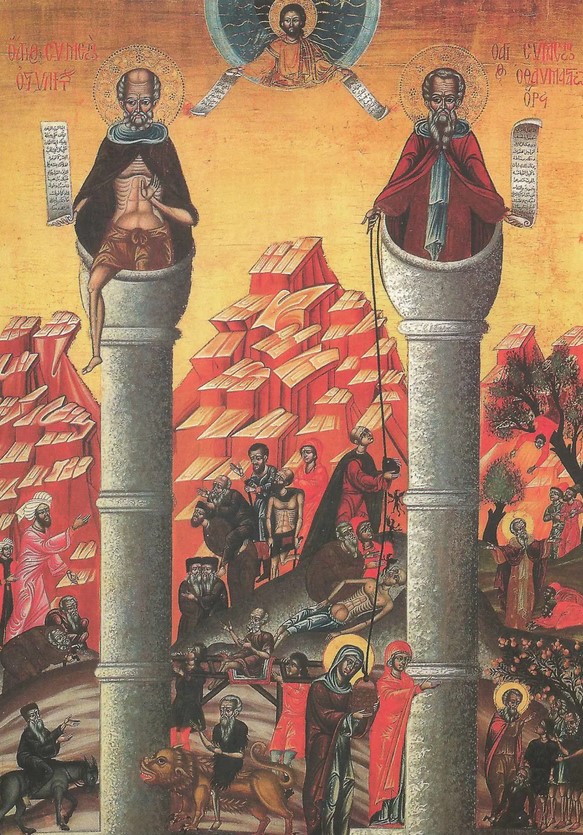

Icon of Simeon Stylites the Elder with Simeon Stylites the Younger. Simeon the Elder appears to be shown at the left stepping down from his pillar in obedience to the monastic elders; the image may also reference a point in his life when, due to an ulcerous leg, he was forced to stand atop his pillar on one leg only. At right is represented Simeon Stylites the Younger (also known as 'St. Simeon of the Admirable Mountain').

Acacius’s refusal to denounce the Council of Chalcedon — whose decrees had reinforced Constantinople’s patriarchal status equal to that of Rome — placed him in direct opposition to Basiliscus. With the support of Constantinople’s citizens and the monastic communities, Acacius symbolically draped the icons of the Hagia Sophia in black and openly accused Basiliscus of heresy. He also enlisted the support of Daniel the Stylite, a highly respected ascetic who lived atop a pillar and held great influence over the people. Daniel came down to lead public processions against Basiliscus, admonishing him and warning him of eternal punishment if he did not retract his decree.

The people rallied around Daniel and Acacius, compelling Basiliscus to withdraw the encyclical. However, this capitulation came too late to save Basiliscus’s rule. In August 476, Zeno returned to Constantinople, besieged the city, and was restored to the throne with the Senate's support. Basiliscus, abandoned and desperate, sought refuge in the cathedral but was betrayed by Acacius and captured. Despite Zeno’s promise of safety, Basiliscus and his family were exiled to Cappadocia, where they were confined to a cistern and left to starve.

Gold tremissis of emperor Zeno (474-491).

With Zeno back on the throne, Acacius briefly found common cause with both the emperor and the Pope in upholding Chalcedonian doctrine. However, in 482, tensions resurfaced when the Monophysite faction in Alexandria attempted to install Peter Mongus as patriarch, supplanting John Talaia. This crisis provided Acacius an opportunity to assert Constantinople's dominance over the Eastern Churches, a move that ultimately challenged Rome's authority.

Acacius advised Zeno to support Peter Mongus, a move that Pope Simplicius condemned. Despite Rome’s objections, Acacius positioned himself as a unifier of the Eastern churches. His key strategy was the drafting of a document called the Henotikon (Union), intended to reconcile the conflicting factions in Egypt.

The Henotikon sought to obscure divisive theological specifics, describing Christ as the “only-begotten Son of God, one and not two,” with no explicit mention of his two natures. This vague formulation was accepted by Peter Mongus but rejected by John Talaia, who appealed to Rome, where Pope Simplicius advocated for his cause.

Portait of Pope Felix III in the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls, Rome

The theological tensions intensified under Pope Felix III, who, in 483, sent Bishops Vitalis and Misenus as envoys to summon Acacius to answer for his defiance of papal authority. Acacius, however, outmaneuvered the envoys, publicly discrediting them, and upon their return to Rome, they faced censure from a synod. In retaliation, Pope Felix III excommunicated Acacius, accusing him of grievous offenses against the Holy Spirit and the papacy.

The excommunication decree was delivered by a messenger named Tutus, who confronted Acacius personally. Acacius refused to acknowledge the document, marking the beginning of the Acacian Schism in 484. In an act of defiance, Acacius struck Pope Felix’s name from the sacred diptychs, which were lists commemorating Church leaders in the liturgy. Even John Talaia, who had opposed the Henotikon, eventually resigned to become the Bishop of Nola, effectively ending his resistance to Acacius’s authority.

With Zeno’s support, Acacius sought to impose the Henotikon across the East, often through persecution of monastic communities resistant to its provisions. By establishing Constantinople’s ecclesiastical primacy, Acacius was, in effect, the leader of Eastern Christianity until his death in 489.

The Acacian Schism signified a profound division between the Church of Constantinople and the Church of Rome. It outlived Acacius by three decades, concluding only in 519 through the efforts of Emperor Justin and Pope Hormisdas. Their reconciliation involved the Patriarch of Constantinople, John II, formally acknowledging the Chalcedonian Creed, thus healing the rift and restoring communion between the Eastern and Western Churches.

Last update: November 3, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE