The Acanthus in Art and Architecture: Evolution and Symbolism Across Cultures

The acanthus plant derives its name from the Greek word akanthos (from ak- meaning "sharp, pointed, piercing" and anthos meaning "flower"). It is a plant with large, spiny leaves.

This type of shrub entered the art world as a striking decorative element. Two rows of acanthus leaves adorn the capitals of columns as a defining motif of the Corinthian style. Its inclusion in the capital, and therefore the invention of the Corinthian order, is attributed by Vitruvius (IV, 1, 10) to Callimachus. Around 415 BCE, he reportedly saw a basket shaped like an inverted cone, randomly covered with such leaves, on the grave of a young girl in Corinth. This vision inspired the essential elements of his invention. Beginning in the 5th century BCE, the acanthus became a primary decorative element in Corinthian capitals.

Through simple stylistic comparisons, we can deduce that the bell shape of the Corinthian capital likely passed into Greek art from Egyptian art of the Third Period. In terms of decoration, while Egyptian motifs primarily imitated and stylized reeds and lotus flowers, Greek art featured a richer variety, influenced by religion, taste, or whim. It is thus likely that Callimachus was indeed the first to apply acanthus leaves as ornamentation on capitals.

In architecture, there are six distinct types of acanthus decoration:

Greek Acanthus – Recognizable by its resemblance to holly or thistle, or, conversely, its overly soft, rounded serrations. An example is the Monument of Lysicrates in Athens.

Acanthus leaf and remains of the capital of a Composite column in Ephesus (in modern-day coastal Turkey). A composite capital can be seen as an Ionic capital set atop a Corinthian capital, with the Ionic volutes at the corners—possibly reduced in size and importance—placed above two tiers of stylized acanthus leaves. The leaves may be rendered quite stiff, schematic, and dry, or they may be intricately carved, naturalistic, and spiky.

Monument of Lysicrates in Athens (334-333 BCE): The capitals and the roof’s grand crest supporting the tripod are richly decorated with acanthus leaves, carved with sharper serrations than those of the spiny acanthus.

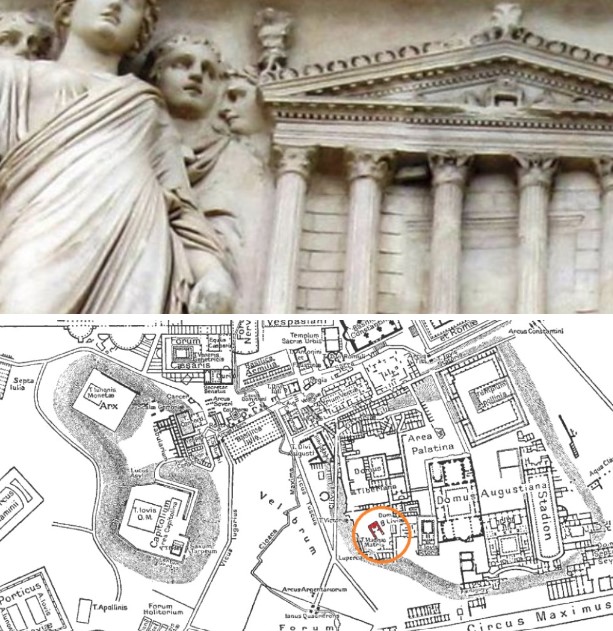

Roman Acanthus – Characterized by rounded leaves. An example is the Temple of the Mother of the Gods on the Palatine Hill in Rome.

Temple of the Mother of the Gods on the Palatine Hill. An ancient Roman relief from the time of Claudius, now preserved at Villa Medici in Rome, portrays a Corinthian and hexastyle temple with a tall staircase. In Roman style, especially toward the end of the Republic and during the Golden Age of the Empire, the acanthus and Corinthian capitals saw widespread application. Here, the acanthus is treated differently than in Greek architecture: more rounded at the edges and tips, it sometimes resembles oak leaves but is always rendered with smooth and expansive forms. By the end of the Roman Empire, acanthus leaves grew more complex, with curled edges, delicate serrations, and geometric outlines while maintaining a soft execution, as seen in friezes carved during the reign of the last emperors. Strongly stylized versions of the spiny acanthus appear in local interpretations in Eastern Roman colonies, such as in Palmyra, Asia Minor, and the Golden Gate in Jerusalem.

Byzantine Acanthus – The spiny leaves become geometric and symmetrical. Examples include the capitals in the upper gallery of San Vitale in Ravenna.

Capital in the upper gallery of San Vitale, Ravenna: The leaves form arches between each other or appear in low relief, so much so that they seem more engraved than sculpted.

Arab Acanthus – Rare, as it is almost always replaced by distinctive Muslim ornamentation (arabesques). A few rare examples can be found in Cordoba and Damascus.

Romanesque-Lombard Acanthus – Used only toward the end of the period, when the chalice-shaped capital with leaves reappears. The strong relief of the edges, veins, and bands decorated with nail-head motifs evoke metallurgical techniques.

Gothic Acanthus – A delicate imitation of the spiny acanthus, often resembling holly or thistle with sharp points and prominent veins. An example can be found in the Cathedral of Siena (1259-1298). Gothic art, however, often favors a varied imitation of local flora and fauna, treated with great mastery.

Decorations imitating acanthus leaves in the Cathedral of Siena.

Renaissance Acanthus – Beginning in the early 15th century, the acanthus leaf becomes the fundamental element in all types of ornamentation.

The pervasive use of the acanthus leaf, both in Italy and abroad, is due not only to the plant's beauty but also to its flexible nature, allowing it to adapt easily to various decorations without losing harmony in form.

Last update: November 4, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: