Accensi

The people of Pompeii enjoyed inscribing insults on wall plaster, creating mocking wordplays. Some phrases likely stemmed from comedic theater, but their vulgarity appears to parody the traditional wisdom such aphorisms were meant to convey. A notable example is found on a basilica wall, playing on the dual meaning of the Latin word accensum (meaning both "auxiliary soldier" and "set on fire"). Someone engraved: “Accensum qui pedicat (!) urit mentulam,” or “he who fucks someone, on fire burns his dick” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, Book IV, 1882).

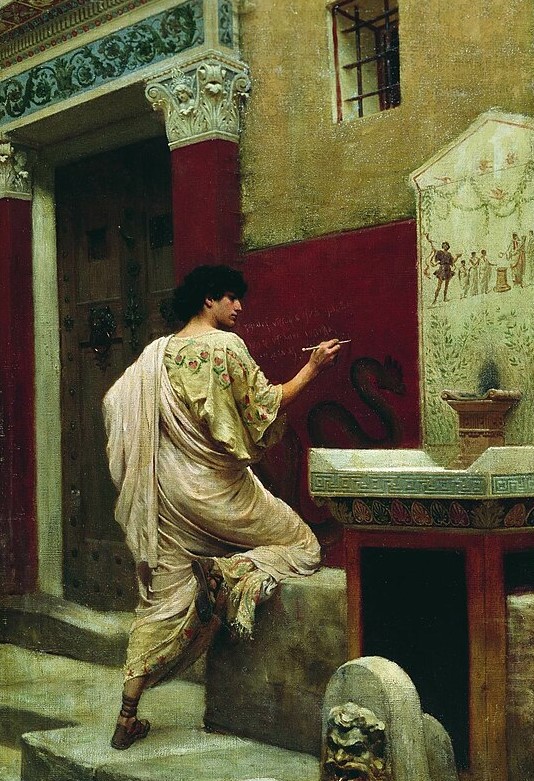

A man carves on a wall (1885), by Stefan Bakałowicz (1857–1947)

The term accensus (literally, "added to the census") first appeared in the works of Cato and Plautus. It designated a citizen without sufficient wealth to belong to the formal classes, hence “added” to the census. Historically, accensi were subordinate assistants assigned to higher-ranking individuals. Over time, their functions evolved.

Originating in Rome’s regal era, they constituted a distinct class of Roman citizens, part of the fifth class in Servius Tullius's early military organization (6th century BCE). These were non-combat military personnel (inermes), valued for their utility, as Livy notes, in the Latin War (340 BCE).

The accensi, Cato writes, were attendants; the word may be from censio 'opinion,' that is, from arbitrium 'decision,' for the accensus is present to do the arbitrium of him whose attendant he is. (Varro, On the Latin Language, 7.58 - ca. 50 BCE)

Alongside the triarii (veteran soldiers forming the last line of defense), the young and inexperienced rorarii, and the accensi served as the final rank, wielding little power and often acting as auxiliary support with slings and stones. When not in combat, they carried messages between officers or retrieved the wounded and buried the dead.

[ca. 325 BCE] The first vexillum was followed by the triarii, veterans of proved courage; the second by the rorarii, or ‘skirmishers,’ younger men and less distinguished; the third by the accensi, who were least to be depended upon, and were therefore placed in the rearmost line (Livy, History of Rome, 8.8.6 - ca. 19 BCE)

Later, accensi became unarmed support soldiers (inermes) accompanying the army. Known as light reserve infantry (accensi ad scripticii, later velites), they filled gaps in maniples and occasionally served as aides to officers.

A detail of Altar or Base of the Vicomagistri. The age of Tiberius (14-37 CE) - Rome, Vatican Museums, Gregorian Profane Museum. The figures could be accensi velati: ministers who, capite velato, are dressed in tunics, but bare feet, carrying in their hands the statuette of the Genius Augusti (figure on left) and those of Lares (central figures)

By the late Republic and early Imperial periods, accensi transitioned to civil public officials under magistrates, often chosen from freedmen. Two categories emerged in Imperial Rome:

- fixed-term accensi: serving for limited terms alongside magistrates, they held roles based on their patron's tenure. Typically freedmen, they gained private rewards, sometimes even equestrian status, from their patrons.

- no fixed-term accensi (or accensi velati): they enjoyed more prestigious, enduring careers.

During early Republic, they were organized as a centuria divided into decuriae. They gathered in arms in the Field of Martius divided into centurions hierarchically defined by the census. Their name comes from the Latin word velati that can be interpreted as 'those who wear (only) the robe and do not carry weapons' to differentiate themselves from the accensi inermes — they symbolized non-combatant status.

By the Imperial era, they see an institutional evolution devoid of any connection with the armed forces, and become holders of only religious duties: a competence, however, that should have already had originally, perhaps in castris. In fact, they become ministers of the official Roman religious cult, under the control of the pontiffs, with function of apparitores ad sacra, attached to the person of the supreme magistrates of the Urbe. They were charged with ensuring that the procedures and liturgical formalities of gestures and minutes were observed during the performance of certain sacra publica celebrated by consuls (e.g. the feriae Latinae). The sacra were ceremonies of a religious character such as the state cult (sacra publica populi Romani).

Consequently the meaning of their name also evolves: velati can be interpreted as 'those who have the habit of performing their sacred role velato capite, that is with head covered by a cloak, according to priestly custom.Prominent in public life, accensi were familiar figures in Roman theater, as in Plautus' plays. They wielded minor powers and benefited personally from their patrons. In the provinces, accensi gained higher status, and those attending emperors or magistrates became prominent due to their elevated rank.

Last update: November 14, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE