The Tradition of Acclamation, From Ancient Rome to the Middle Ages

Originally, an acclamation (acclamatio in Latin; aktologhia in Ancient Greek) was an expression of a desire or a prayer for divine intervention. Among the Romans, it came to denote any verbal manifestation of joy, approval, or good wishes, often expressed through clamor and even unruly noise. Acclamations could be collective or individual, taking place in public gatherings or private events.

Farfa Abbey, Rieti, Italy. Reconstruction of the early Christian sarcophagus (4th century CE) with niches with Traditio Legis, that is the "Delivery of the Law" by Christ to the apostle Peter, in the presence of Paul acclamating. Christ is in the center of the relief, bearded and standing on the paradise mountain; while Paul is in the niche that follows His right, he is facing the Master who with his right hand (lost) makes the gesture of acclamatio while with his left holds a scroll.

Acclamations in Roman Life

Acclamations were integral to many aspects of Roman public life:

- Marriage Ceremonies: Exclamations such as Talassio! or Io Hymen Hymenaee!

- Public Entertainment: Celebrating a successful performance or game.

- Oratory Success: Applauding speakers with cries of Bene et praeclare!

- Imperial Appearances: Welcoming political leaders or celebrating the accession of an emperor with cheers like felicissima! felicissime!

- Proclamations of New Emperors: Popular cries like omnes, omnes! or placet universis!

- Triumphal Processions: Chanting Io triumphe! for victorious generals.

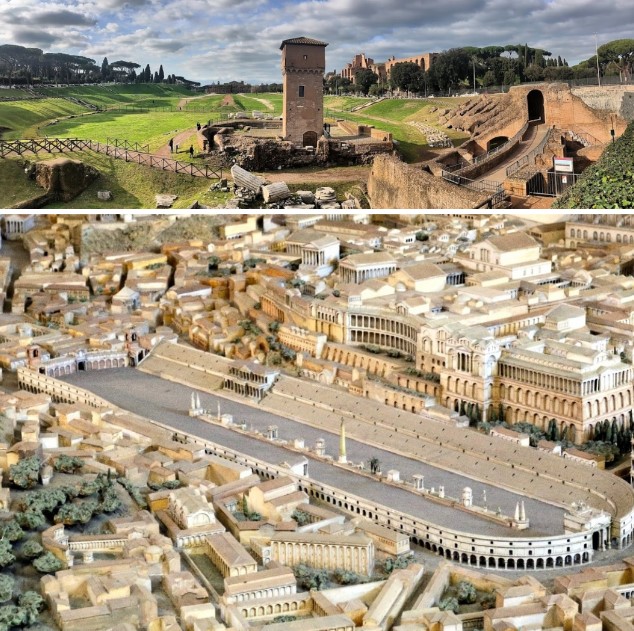

The Circus Maximus is the largest building for public entertainment in antiquity and one of the largest of all time (600 metres long by 140 metres wide) and is related by a legend to the very origins of the city: the Rape of the Sabine Women took place here.

The people often used the Circus Maximus as a venue for acclamations. Roman historian Pliny described it as “the seat of the people,” where citizens gathered to express approval or dissent. Tacitus noted that the crowd felt at home in the circus and theaters, using these spaces to voice their opinions directly to the emperor.

'The Death of Tigellinus' by Cornelius Tacitus, The History, I, 72.

Tacitus recounts the infamous death of Ofonius Tigellinus (c. 10 – 69 CE), a prefect of the Roman imperial bodyguard, known as the Praetorian Guard, under Emperor Nero. As a friend of Nero he quickly gained a reputation around Rome for cruelty and callousness. During the second half of the 60s, however, the emperor became increasingly unpopular with the people and the army, leading to several rebellions which ultimately led to his downfall and suicide in 68. When Nero's demise appeared imminent, Tigellinus deserted him and shifted his allegiance to the new emperor Galba. Unfortunately for Tigellinus, Galba was replaced by Otho barely six months after his accession. Otho ordered the execution of Tigellinus, upon which he committed suicide.

During the reign of Galba Tigellinus had been screened by the influence of Vinius, who alleged that he had saved his daughter. And doubtless he had preserved her life, not indeed out of mercy, when he had murdered so many, but to secure for himself a refuge for the future. For all the greatest villains, distrusting the present, and dreading change, look for private friendship to shelter them from public detestation, caring not to be free from guilt, but only to ensure their turn in impunity. This enraged the people more than ever, the recent unpopularity of Vinius being superadded to their old hatred against Tigellinus. They rushed from every part of the city into the palace and forum, and bursting into the circus and theatre, where the mob enjoy a special license, broke out into seditious clamours. At length Tigellinus, having received at the springs of Sinuessa a message that his last hour was come, amid the embraces and caresses of his mistresses and other unseemly delays, cut his throat with a razor, and aggravated the disgrace of an infamous life by a tardy and ignominious death.

Roman acclamations are represented in coins and bas-reliefs, often showing figures alongside a sovereign in deferential poses, raising their right hands. This tradition extended from Rome to Byzantium, influencing ceremonies at Constantinople’s Hippodrome and even Christian liturgical practices.

Christian and Medieval Acclamations

By Christian Phrases like Hosanna, Benedictus, Amen, Alleluia, etc., during the early Christian era and Middle Ages, acclamatio evolved to signify joy, sorrow, or election in ecclesiastical contexts. For instanceit was used to select bishops and popes, such as Pope Fabian in the 3rd century, or in hymns like Te Deum, etc.

During the Byzantine Empire, imperial acclamations became more elaborate, reflecting Eastern ceremonial influences. Despite this, some retained Roman simplicity, such as Tu bene vincas! or Sanctus Deus, Sanctus immortalis, miserere nobis; multos annos imperatoribus during the Council of Chalcedon.

A 5th-century depiction of acclamation appears on the wooden door of the Basilica of Santa Sabina in Rome. It features Christ presenting the Law to Peter, with Paul depicted in a pose of acclamation.

Wooden door of the basilica of Santa Sabina in Rome. A figuration of acclamatio from 425-450 CE is in a panel of the wooden door of the basilica of Santa Sabina in Rome, where it depicts the presentation of a sovereign to the people. The doorposts of this portal are made from frames of Roman age; its 18 panels carved in relief (but once, the original ones were in all 28) depict Scenes of the Old and New Testament.

In the Germanic tradition, acclamations approved laws and royal appointments. For example, Charlemagne’s coronation in Saint Peter’s Basilica elicited thunderous cheers, as described in the Liber Pontificalis. The crowd proclaimed:

To Charles... Augustus, crowned by God, great and peaceful emperor of the Romans, life and victory!

This demonstrated the continuity of Roman imperial ideals in the new empire.

Last update: November 17, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE