Acerrae, Oscan city of Campania

Acerra (in Latin Acerrae) is one of the oldest cities in Campania, located west of Nola and about 14 kilometers northeast of Naples. Its history is indeed very ancient, and the origins of its name are debated.

The first settlements are prehistoric, made possible by the rich and dense vegetation, abundant wildlife, and numerous waterways.

In Campania, between the late 10th and early 9th century BCE, groups of Etruscans arrived, while in the second half of the 8th century BCE, Greeks came to the area. They founded flourishing cities or colonies or, more simply, expanded existing settlements.

Acerra and Acheruntia

In the 6th century BCE, Etrusco-Campanian centers such as Capua, Nola, and Pompeii were transformed into proper cities, while others remained small agricultural settlements scattered across the fertile countryside, thanks to the volcanic soil. Among these was the territory of Acerra, whose earliest evidence dates back to the late 6th and early 5th centuries BCE. There was no actual city yet; rather, according to recent archaeological research, it was likely inhabited by the Ausones.

The Ausones were an ancient Italic population settled in the Campanian region during the Iron Age. Their origins are uncertain: some ancient writers, such as Antiochus of Syracuse or Aristotle, considered them an Oscan people, while others, like Polybius, identified them as Latins, more precisely a Latin-Faliscan group based on linguistic considerations.

Some statues of the Osci depicting the goddess Mater Matuta - Archaeological Museum of Campania in Capua.

By the late 5th century BCE, the rich Campanian plain, crossed by the Volturno and Clanis (Clanio) rivers, was occupied by the Campani people, an Italic population belonging to the Oscan group, who displaced the Etruscans from Capua and the Greeks from Cumae, and called the present-day Acerra Akeru (in the Oscan language, meaning "elevated place"). Acerra became part of the Oscan or Etruscan dodecapolis headed by Capua.

The Oscans were an Indo-European-speaking population of Samnite origin from pre-Roman ancient Campania. They came from the Lucanian territories where the river Acheron (modern-day Brandano) flowed. This river was considered the river of the underworld, marking the entrance to the realm of the dead, the boundary that all souls of the deceased had to cross, inevitably and irreversibly, on Charon’s boat. This symbolic ferry crossing represented the transition to the afterlife: an even older and widely spread image in preceding mythologies, particularly in the Egyptian Nekyia.

It is assumed that the city was inhabited by Oscans originating precisely from the Lucanian territories where the Acheron River flowed, near the current Acerenza (Acheruntia). The Latin poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus (65–8 BCE) wrote: "Quicunque celsae nidum Acherontiae" (Book III). He mentioned it as Acheruntia, later Acerenza, meaning "very high place," where eagles loved to nest.

Acerrae could also have another etymological interpretation. Indeed, it might derive from cerrus ("Turkey oak"), referring to the tree of the Fagaceae family (Quercus cerris). The prefix "a-" could be a privative alpha, indicating that before the city's foundation, the territory was covered by Turkey oak forests, which were gradually removed as the city was built.

In ancient times, there was a habit of naming places based on their physical characteristics: thus, Nocera derived its name from nucerium ("walnut grove"), Pomaro from pomarium ("apple orchard"), or Melito from maletus ("apple orchard").

Livy recounts that in 332 BCE, after the First Samnite War and the Latin War, the people of Acerrae were the first among the Roman provinces to be granted civitas sine suffragio. This meant Roman civil citizenship rights without voting rights, a privilege Rome granted to cities that had demonstrated loyalty during particularly difficult times, such as the threat posed by the Samnites at that time.

The Samnites were an ancient Italic people settled in the central-southern area of the Peninsula. They formed a confederation of peoples, the Samnite League, and were closely related to the Oscans.

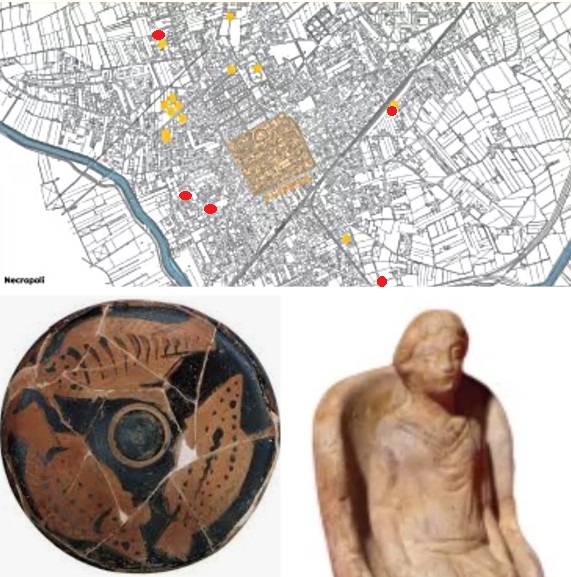

After this episode, archaeological evidence becomes more substantial, demonstrating how Acerrae underwent a complete transformation between the late 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, assuming an urban dimension. The urban layout was based on an orthogonal street grid, surrounded by fortifications, with several necropolis clusters distributed around the perimeter of the ancient city. These burial areas were used for about a century.

Map of the city of Acerra and its necropolises from the Hellenistic period (yellow) and Imperial period (red); a plate with fish motifs from the Hellenistic necropolis of Acerra, second half of the 4th century BCE; and a figurine on a throne from the Roman necropolis.

During the Second Punic War (218–201 BCE), the city remained loyal to Rome but was conquered and partially destroyed by Hannibal, who besieged it in 216 BCE.

[ca. 216 BCE] At first the Carthaginian tried to persuade the men of Acerrae to make a voluntary surrender, but when he found that their loyalty remained unshaken he made preparations for a siege and an assault (Livy, History of Rome, 23.17 - ca. 19 BCE)

Hannibal, seeking allies against Rome, punished the people of Acerrae with a siege when he failed to persuade them to support him. During the night, the inhabitants of Acerrae took advantage of gaps left unguarded and the darkness to seek refuge in the city.

[ca. 210 BCE] The people of Nuceria and Acerrae having complained that they had nowhere to live, as Acerrae was partly destroyed by fire and Nuceria completely demolished, Fulvius sent them to Rome to appear before the senate (Livy, History of Rome, 27.3 - ca. 19 BCE)

The city of Acerrae, meanwhile, was destroyed. Hannibal demolished and burned the buildings before abandoning the site. After the Carthaginians left Campania in 211 BCE, the inhabitants of Acerrae returned to their land. The city was rebuilt by the Romans, becoming an important municipium with greater autonomy and Roman citizenship rights.

[ca. 216 BCE] Marcellus was equally anxious to assist the besieged garrison, but he was detained by the Vulturnus being in flood, and also by the entreaties of the people of Nola and Acerrae who feared the Campanians in case the Romans withdrew their protection (Livy, History of Rome, 23.19 - ca. 19 BCE)

View of Acerra with Mount Vesuvius in the background and footprints in the ash left by a person fleeing the eruption of the Avellino Pumices.

But it wasn’t only wars that devastated the city. The Latin poet Publius Vergilius Maro (70–19 BCE) mentions it in the second book of the Georgics (v. 225): he described it as “… Vesuvius, and the Clanian flood, Acerrae’s desolation and her bane.” The frequent flooding of the nearby Clanis River, coupled with eruptions from nearby Mount Vesuvius, gradually made the area dangerous, forcing the population to abandon the site.

We do not have records of all the eruptions, of course, but we do know their effects. For example, the eruption of 1813 resulted in ashfall, while the eruption 4,000 years ago, even more devastating than the one that destroyed Pompeii, known as the "Avellino Pumice eruption" (2000–1800 BCE), caused a rupture in the occupation of the Campanian plain. Entire villages were buried under ash and pumice, and the inhabitants of the area fled in search of safer places. Archaeological excavations have uncovered numerous settlements from the Early Bronze Age (2300–1800 BCE) buried beneath the Avellino Pumice.

After the eruption, life resumed only around 1400–1300 BCE, when previously abandoned sites north of the Clanis River were reoccupied, and Bronze Age necropolises, such as the one in the Gaudello area, were reused.

The Social War, 90 BCE. AR Denarius. Mint moving with Gaius Papius Mutilus. Head of Bacchus facing right, adorned with an ivy wreath; MUTIL EMBRATUR in Oscan on the right / A bull goring a wolf below; C PAAPI in Oscan in the exergue.

Rebuilt after the Second Punic War, Roman-period Acerrae retained the quadrilateral layout of its center. Recent archaeological surveys conducted in the Maddalena district have identified sections of a city wall dating back to approximately the 4th century BCE.

For many years, Acerrae seemed to experience the quiet life of a city that had become “Roman” in every sense. Its language and institutions reflected the new culture.

The Social War (90 BCE), which bloodied many parts of Italy and spread to Campania, where the Roman yoke was bitterly resented, particularly in Capua, also involved Acerrae. During the war, however, the city was the site of a significant battle in which the Roman consul Sextus Caesar was victorious against the Italic army led by Gaius Papius Mutilus.

Gaius Papius Mutilus (in Oscan: Gaavis Paapiís Mutíl), a member of the Samnite Pentri tribe, was a Samnite leader and general, as well as Embratur (an Oscan title for the supreme leader of the Samnites responsible for commanding their army). He led the Samnite military forces during the Italic revolt against the Romans in 90–91 BCE. At the start of the conflict, he operated successfully against the Romans in Campania. Using a stratagem, he captured Nola, incorporating its local garrison into his army. The Roman officers who refused to defect were left to starve, and the praetor Lucius Postumius was killed. Mutilus thus managed to bring several other cities under his control, either by conquering them militarily or persuading them to surrender without bloodshed. Mutilus also laid siege to Acerrae.

The Roman consul Lucius Julius Caesar (c. 135–87 BCE), grandfather of the future triumvir Mark Antony (83–30 BCE), was sent to relieve Acerrae, which was under siege by Mutilus. The Roman politician of the Republic era could rely on a strong contingent of Numidian cavalry. However, Mutilus cunningly displayed Prince Oxinte (the son of the Numidian king Jugurtha, who had been exiled by the Romans to the city of Venusia) dressed in regal attire in an attempt to induce the Numidian forces to defect. Despite this, the Samnite attack on the Roman camp failed; after suffering heavy losses, the Italic forces were forced to retreat. This episode marked the first serious defeat of the Italics in the Social War.

The Cathedral of Acerra (Duomo di Acerra), likely built on the remains of an ancient Roman temple dedicated to Hercules; sources attest it was already a cathedral by 1058.

In 22 BCE, during the reign of Augustus, Acerrae was awarded as a reward to Roman veterans, becoming a military colony and losing all its independence. As a colony, Acerrae lost the last vestiges of its native culture, and later, as a Prefecture, it had to renounce its own laws and the power of its magistrates. It was governed by a Prefect according to laws imposed by Rome. When it became a Municipium, it obtained voting rights in Roman assemblies, allowing citizens of Acerrae to hold magistracies in Rome itself.

In Acerrae at that time, the cults of the Egyptian gods Isis and Serapis were widespread, and a temple was likely dedicated to them, as reported by epigraphic sources. These sources also attest to the presence of a temple dedicated to Hercules (over which the current cathedral now stands)

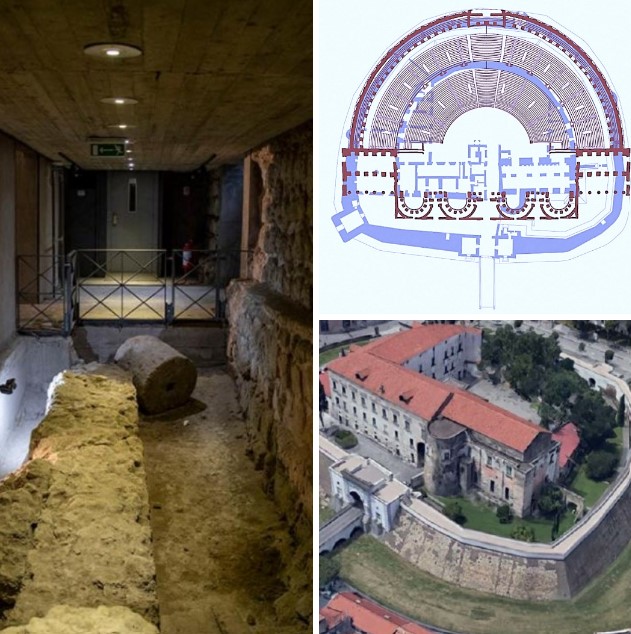

The Castle of the Counts (Castello dei Conti), which incorporates the remains of one of the few known monuments of ancient Acerra: the Roman theater.

An amphitheater, probably located beneath the Castle of the Counts due to its particular layout, was identified, in the wing of the old stables, structures related to the scene of a theater dating to the 1st–2nd century CE.

Remembered by ancient historians as a small town, Acerrae continued to exist until the 3rd–4th century CE.

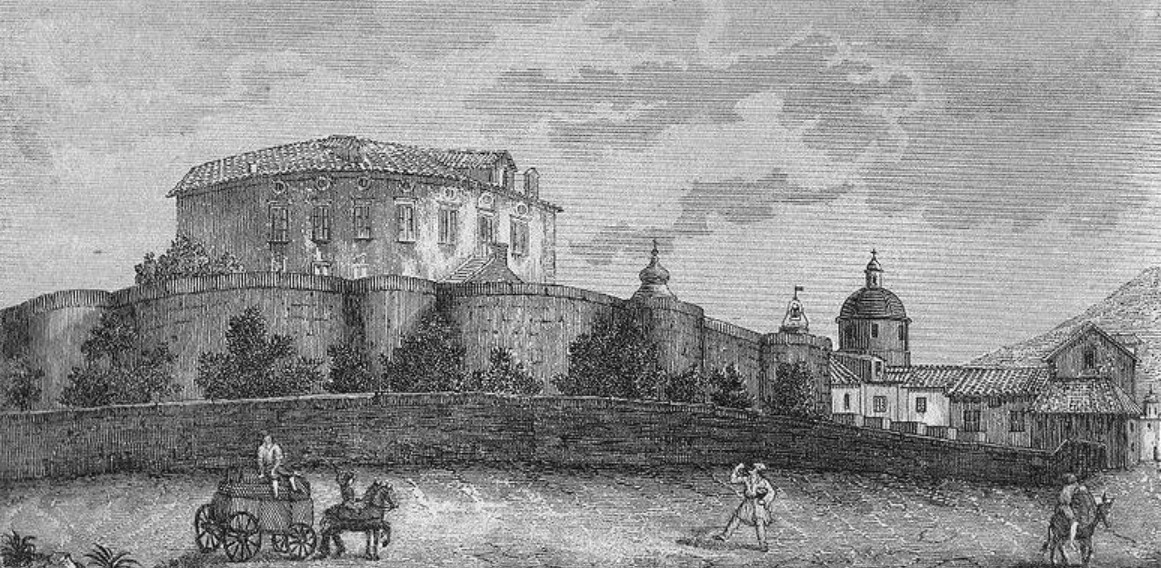

Acerra: The Baronial Castle in the 19th century.

In the medieval period, from the 6th to the 10th century CE, the center participated with varying fortunes in the struggles between the Byzantines of the Duchy of Naples and the Lombards of the Principality of Capua.

In 494 CE, the city was annexed to Naples and much later came under Lombard rule. The Lombards built a castle there in 826, which was destroyed by the Duke of Naples, Bono. It suffered devastation and pillaging by the Saracens (circa 881) and came under Norman control at the end of the 9th century.

Meanwhile, the castle was rebuilt, as indicated by decorative elements uncovered during recent renovation and restoration works. Counts of this era included Goffredo, Ruggiero, Roberto, and Riccardo of Medania.

The daughter of Roberto was Queen Sibilia, an Acerran who married Tancred, King of Naples.

In the Swabian era, one notable feudal lord was Thomas Aquinas, linked to Emperor Frederick II.

As the list of rulers during the Angevin and Aragonese phases would be long, notable mentions include the counts from the Origlia and del Balzo Orsini families, as well as Count Frederick of Aragon, the future King of the Two Sicilies.

Later, the De Cardenas family took control, starting in 1496. The first family member was Ferdinand, while Maria Giuseppe was the last, ill-fated countess, who died in 1812, two years after feudalism was abolished in Acerra.

Last update: November 28, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE