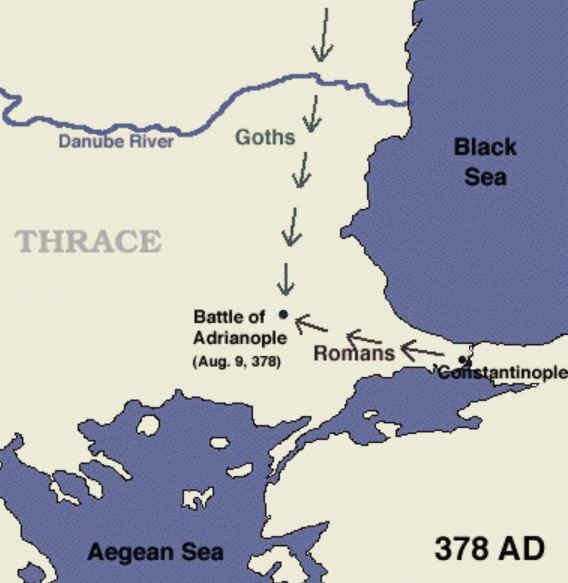

The Battle of Adrianople in 378 was the beginning of the end for the Roman empire.

The Roman empire grew weaker, and the barbarians were on the rise. Rome was no longer in its prime, yet it still could muster a tremendous force. The western empire at the time was ruled by Gratian, while in the east was ruled by his uncle Valens.

On August 9, 378 CE, one of the most decisive and tragic defeats in Roman history unfolded near the town of Adrianople (Hadrianopolis, modern-day Edirne, Turkey). The exact location where the Goths were camped and where the Battle of Adrianople took place has never been definitively identified. But, according to Syrian historian Ammianus Marcellinus (c.330 - c. 395), there was a Turkish village called Muratli it might be that location. That village is nestled among low hills that, at the time, were likely partially cultivated with vineyards and olive groves. There is a water source — a spring — making it an ideal spot for a camp and easy to defend by positioning a barricade of wagons on the surrounding heights.

Muratlı is a municipality and district of Tekirdağ Province, Turkey

The Eastern Roman army, led by Emperor Valens, launched an ill-fated attack on a Gothic force comprising both Visigoths and Ostrogoths. The Roman army was routed, and Valens himself perished on the battlefield. This catastrophic loss is often seen as a pivotal moment that accelerated the eventual decline of the Roman Empire in the 5th century.

Background to the conflict

The events leading up to the Battle of Adrianople were set in motion by the movement of the Huns, a nomadic people originally from Mongolia.

Ammianus Marcellinus described the Huns as men apparently primitive pastoralists who knew nothing of agriculture. They had no settled homes and no kings; each group was led by primates. As warriors, the Huns inspired almost unparalleled fear throughout Europe. They were amazingly accurate mounted archers, and their complete command of horsemanship, their ferocious charges and unpredictable retreats, and the speed of their strategical movements brought them overwhelming victories.

The Huns Empire (376-441)

By the 370s CE, the Huns, displaced from their homeland by Chinese forces, had begun migrating westward into Eastern Europe. Between 372 and 376, their relentless pressure forced the Goths — initially residing near the Volga, Don, and Dnieper Rivers — further west toward the Danube River and into the territory of the Eastern Roman Empire.

In a bid to secure protection from the advancing Huns, the Goths sought asylum within the Roman Empire. Emperor Valens, seeing an opportunity to bolster his military ranks, allowed the Goths to settle in the empire under the condition that they would serve in the Roman army. The Romans also promised to provide the Goths with essential supplies. However, corruption and greed among Roman officials led to significant mistreatment of the Gothic refugees. Instead of fulfilling their agreements, many Roman officials either sold supplies that were supposed to be free or withheld them altogether, leaving the Goths in dire straits.

Tensions escalated in 377 when a conference between the Visigoth leaders and Roman authorities turned violent. The Romans attempted to ambush and capture the Visigoth leadership, but some managed to escape. These leaders rallied their forces, joining with the Ostrogoths to launch raids across Roman settlements in the region of Thrace.

The Battle of Adrianople (378 CE)

The Lead-Up to the Battle

Throughout the summer of 378, Roman forces regained some control, rounding up Gothic fighters and attempting to suppress the growing unrest. By July and August, the Gothic forces were largely cornered near Adrianople. Valens had been expecting reinforcements from the Western Roman Emperor Gratian, who was marching to assist. However, rather than waiting for Gratian's arrival, Valens, perhaps eager for a quick victory, decided to attack the Goths without support.

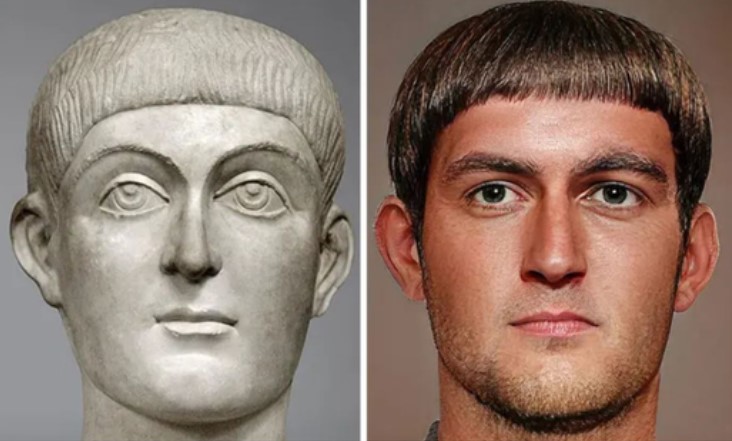

Marble bust possibly representing Valens or Honorius - Capitoline Museums, Rome

On August 9, Valens led his troops from Adrianople to confront the Gothic wagon camp. The attack began prematurely, with Valens ordering a cavalry charge before his infantry had fully deployed. Unbeknownst to the Romans, the Gothic cavalry, which had been raiding nearby, had returned just in time to counter the Roman assault. They swiftly engaged the Roman cavalry, driving it from the battlefield. With their cavalry defeated, the Roman infantry was left exposed. The combined strength of the Gothic infantry and cavalry then encircled and decimated the Roman forces. The battle was a disaster for the Romans, with two-thirds of their army—including Emperor Valens—slain.

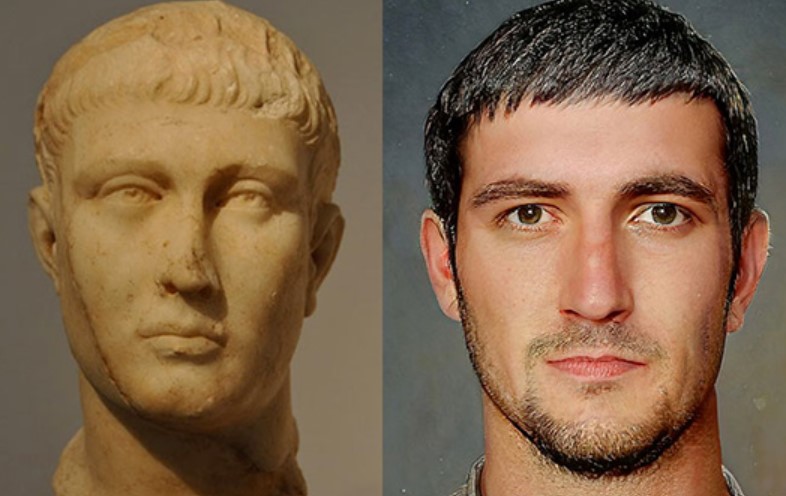

Bust of Theodisus I. Founded in Aphrodisias - Aydın, Turkey

Aftermath and consequences

The loss at Adrianople dealt a crushing blow to the Eastern Roman Empire, but it was more than just a military defeat. The battle revealed the vulnerability of the Roman army and the empire’s declining ability to control its borders. It took the new Eastern Roman Emperor, Theodosius I, until 383 to reestablish some semblance of stability. Theodosius managed to drive many of the Goths back across the Danube River, while others were permitted to remain in Roman territory under more formalized agreements, even being granted Roman citizenship.

While this temporary peace provided the Eastern Roman Empire with much-needed relief, it also sowed the seeds for future conflicts. The integration of Goths into Roman society and the military offered short-term solutions but also created a growing faction within the empire that was not fully Romanized and often maintained divided loyalties.

The consequences of Adrianople rippled through the decades. In 401, the Gothic leader Alaric, who had previously served in the Roman army, led a mixed Gothic-Roman force in an invasion of Italy. Although this invasion was initially repelled in 402, the peace that followed was fragile. By 409, Alaric had invaded Italy again, and on August 24, 410, his forces famously captured and sacked Rome. This event marked a significant turning point in the decline of the Western Roman Empire.

The Battle of Adrianople was not merely a military defeat, but it marked the beginning of a transformative era in Roman history, one in which external pressures and internal weaknesses converged to bring about the eventual fall of the Western Roman Empire.

The great sarcophagus of Ludovisi (3rd century) shows a victory of the Roman soldiers over the barbarians. Roman National Museum nazionale in Altemps Palace, Rome

The alternative View of the Battle of Adrianople

The battle of Adrianople is undisputedly a turning point in history, because of the scale of Rome's defeat. However, it is worth pointing out that not everyone subscribes to the above description of the battle. The above interpretation is largely based on the writings of Sir Charles Oman, a famous 19th century military historian.

There are those who don't necessarily accept his conclusion that the rise of heavy cavalry brought about a change in military history and helped overthrow the Roman military machine.

Some explain the Roman defeat at Adrianople simply as follows: the Roman army was no longer the deadly machine it had been, discipline and morale were no longer as good, Valens' leadership was bad. The surprising return of the Gothic cavalry was too much to cope with for the Roman army, which was already fully deployed in battle, and hence it collapsed.

It was not any effect of heavy Gothic cavalry which changed the battle in the barbarians' favour. Far more it was a breakdown of the Roman army under the surprise arrival of additional Gothic forces (i.e. the cavalry). Once the Roman battle order was disrupted and the Roman cavalry had fled it was largely down to the two infantry forces to battle it out among each other. A struggle which the Goths won.

The historic dimension of Adrianople in this view of events restricts itself solely to the scale of the defeat and the impact this had on Rome. Oman's view that this was due to the rise of heavy cavalry and therefore represented a key moment in military history is not accepted in this theory.

Last update: September 30, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: