Virgil's Aeneid: Epic Foundations of Roman Ideology and Literary Legacy

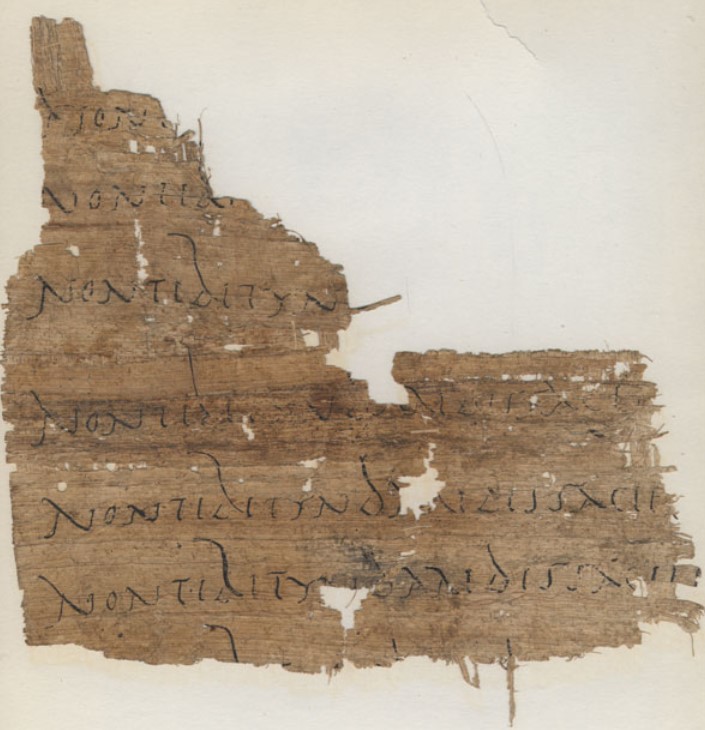

A fragment of a Papyrus from Hawara (near Fayum, Egypt) inv. 24 - Vergil (1st century AD). It has a line of the Aeneid (II, 601) repeated 7 times, probably a writing exercise by one hand, that translates: 'Non tibi Tyndaridis facies invisa Lacaenae' (It is not the hated face of Spartan Helen... = Helen of Troy). It is displayed at the British Museum, London.

Virgil's Aeneid (from Latin Aenēis -eĭdos) is universally recognized as one of the cornerstones of Latin literature and a seminal work in the Western literary canon. Written during the transition from the Roman Republic to the Empire under Augustus, it is in dactylic hexameter.

Hexameter is a line of verse containing six feet, usually dactyls (′ ˘ ˘). Dactylic hexameter is the oldest known form of Greek poetry and is the preeminent metre of narrative and didactic poetry in Greek and Latin. Its position is comparable to that of iambic pentameter in English versification.

The Aeneid is an epic poem, which narrates in 12 books the trials and triumphs of Aeneas, the son of Venus, in the aftermath of the Trojan War.

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (65-8 BCE, aged 57), Publius Vergilius Maro (70-19 BCE, aged 51) and Lucius Varius Rufus (70-19 BCE, aged 51) at the house of Gaius Cilnius Maecenas (at right, 68-8 BCE, aged 60), by Charles Jalabert - Late 19th Century

The poet Publius Vergilius Maro (70-19 BCE, aged 51), usually called Virgil or Vergil in English, spent the last ten years of his life (29-19 BCE) working on the Aeneid, but never managed to give it a final polish. As a result, the text contains some inconsistencies, gaps, minor contradictions, and 53 unfinished verses which have intrigued scholars for centuries. Some view them as a testament to Virgil's perfectionism, while others believe they offer a unique glimpse into the poet’s creative process, revealing how the epic was evolving even as he neared his death.

According to the Vita (life) by the Roman grammarian and teacher of rhetoric Aelius Donatus (315-380 CE, aged 65), Virgil had originally written the work in prose, later giving it a poetic form without much order or continuity. This detail hints at the immense effort involved in crafting the epic, whose structure emerged slowly over time.

In 19 BCE, Virgil decided to travel to Greece and Asia, intending to spend three years completing the poem. His journey reflects the significance the poet placed on classical education. Both regions were centers of learning and culture, particularly in rhetoric and philosophy.

He asked his friend Varius Rufus to burn the Aeneid if he did not return. Rufus refused. When Virgil returned to Italy that September, gravely ill, he arrived in Brindisi and, sensing his impending death, requested the manuscript to burn it himself. Yet, no one dared to fulfill his wish.

Despite being incomplete, the Aeneid had already gained fame. The Latin elegiac poet Sextus Propertius (c. 50/45 - c. 15 BCE, aged c. 35) had publicly announced its existence, and writers like Titus Livius (59 BCE - 17 CE, aged 42), Horace, and Albius Tibullus (54-19 BCE, aged 35) had drawn inspiration from its themes. Virgil’s creation was thus known to his contemporaries, despite his desire for it to remain unfinished.

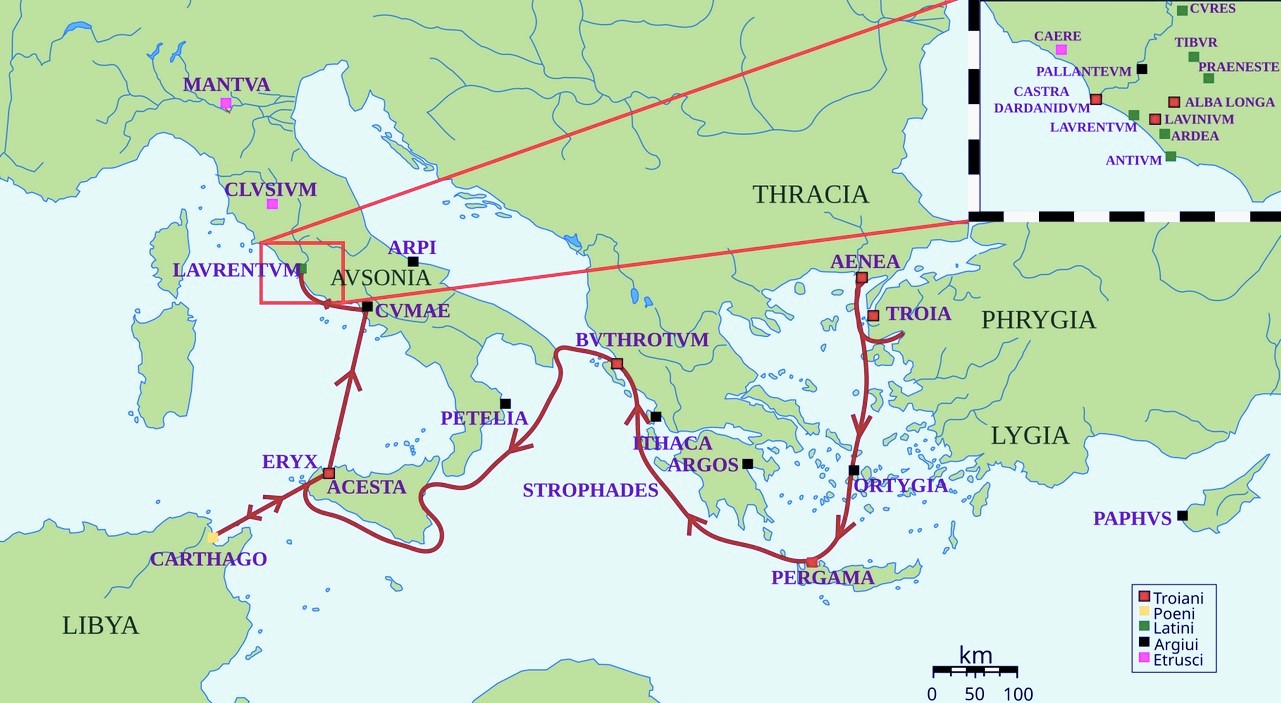

Map of Aeneas' fictional journey

Following the sack of Troy, Aeneas embarks on a perilous journey that leads him to Italy, where, according to Roman mythology, he would establish the lineage that would ultimately birth the Roman people.

Composed by Virgil, the Aeneid draws heavily from earlier literary traditions, most notably from the works of Homer, Lucretius, Ennius, and Apollonius of Rhodes.

Virgil’s reverence for Homer is woven throughout the fabric of his poem. The opening line, "I sing of arms and a man," deliberately echoes the epic tone of the Iliad and Odyssey, setting the stage for Aeneas’s odyssey-like wanderings and his Iliad-style battles.

The first half of the Aeneid mirrors the structure of the Odyssey, earning it the informal title of the "Virgilian Odyssey," while the latter half parallels the war-driven narrative of the Iliad. Yet Virgil’s homage to Homer is far from imitation. By placing Aeneas in scenarios that recall those of Odysseus or Achilles, Virgil invites readers to compare his hero to these legendary figures, often emphasizing Aeneas’s unique qualities - especially his sense of duty, or pietas, which sets him apart as the quintessential Roman hero.

The Aeneid is not only a heroic tale but also a profound reflection on Roman values and identity. Aeneas is the embodiment of pietas - a Roman virtue denoting duty to the gods, one’s family, and the state - making him a model of the ideal Roman citizen. His unwavering commitment to his divine mission, even at great personal cost, would have resonated deeply with Virgil's contemporaries during the transitional period of Augustus’s rule.

Aeneas and Dido (Mars and Venus); National Archaeological Museum of Naples (inv. 112282); fresco from Pompeii, House of the Citharist (I, 4, 5), third style (10 BC - 45 AD).

An etiological myth is a myth trying to explain the origin of a name or a rite or a tradition, whose origin was lost memory or it was intended to ennoble it by reconnecting to illustrious characters or events of antiquity. The Aeneid incorporates key etiological myths, such as the tragic story of Dido, which serves to explain the historic enmity between Rome and Carthage.

The episode involving Dido, queen of Carthage, is one of the most emotionally charged and memorable moments in the poem. After being shipwrecked on the shores of her city, Aeneas and his crew are welcomed with open arms by the gracious queen. With Venus’s intervention, Dido falls passionately in love with Aeneas and dreams of him staying in Carthage to rule beside her. But Aeneas is reminded of his fate in Italy, and, despite his own feelings, he departs, leaving Dido devastated. In her grief, Dido constructs a pyre from Aeneas’s belongings and takes her own life, cursing his descendants and foretelling the rise of Hannibal, Rome’s greatest adversary. When Aeneas later encounters her shade in the Underworld, Dido’s silence and refusal to acknowledge him adds a poignant layer to her tragic story.

Dido’s character is an intricate blend of mythological archetypes. Initially, she is a regal and hospitable figure, akin to characters like Alcinous and Arete, but as her narrative unfolds, she takes on traits more reminiscent of Medea, with her eventual turn to magic and curses. While modern audiences often sympathize with Dido’s plight, Virgil's Roman readers may have associated her with Cleopatra, casting her in the light of a foreign queen who threatens Roman ideals, much like the Egyptian ruler’s infamous alliance with Mark Antony during Rome’s civil wars.

Scholarly interpretations of the Aeneid have long been divided, particularly regarding its political message.

- Written during the transition from the Roman Republic to the Empire under Augustus, the poem has often been read as a celebration of the new regime. Virgil appears to herald Augustus as the harbinger of a golden age, linking him to the divine lineage of Aeneas and portraying the emperor’s rule as the fulfillment of Rome’s manifest destiny.

- However, some critics detect a more complex or even critical undercurrent in the epic. The brutal conflict in Italy, which occupies the latter half of the poem, has been interpreted as an allusion to civil strife, particularly the Battle of Perusia (41 BCE), an event Augustus would likely have preferred to erase from memory. Furthermore, Aeneas’s decision to kill Turnus in the poem’s final moments, despite Turnus’s plea for mercy, has been viewed by some as a veiled critique of the merciless tactics Augustus employed in consolidating power.

Nonetheless, this anti-Augustan reading is contested by many scholars, who argue that the poem’s allusions to Homeric epics are more significant than any contemporary political parallels. According to this view, Aeneas’s actions - especially his slaying of Turnus - reflect the moral values of the ancient world, rather than a specific judgment on Augustus’s rule. - Others suggest that Virgil intentionally left his stance ambiguous, crafting a narrative that could be interpreted in multiple ways, allowing readers to draw their own conclusions about the emperor and his regime.

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (c.35-96, aged 61), the famed Roman rhetorician, ranked Virgil nearly alongside Homer, arguing that Virgil faced an even more challenging task in writing his epic. Later poets, like Publius Papinius Statius (c.45 - c.96, aged 51), revered the Aeneid as the zenith of Latin epic poetry, acknowledging that surpassing Virgil’s achievement was nearly impossible. Yet Virgil himself was famously dissatisfied with his work. On his deathbed, he allegedly requested that the Aeneid be burned, though Augustus intervened to ensure its preservation.

Today, Virgil’s Aeneid continues to be regarded as one of the most significant works of world literature, a masterful blend of Roman ideology and timeless human themes. The poem’s enduring legacy, much like the empire it helped to mythologize, remains a towering influence across the centuries.

Last update: September 30, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

References:

- Hawara, Biahmu, and Arsinoe : with thirty plates by Petrie, W. M. Flinders (William Matthew Flinders), Sir, 1853-1942; Griffith, F. Ll. (Francis Llewellyn), 1862-1934; Sayce, A. H. (Archibald Henry), 1845-1933; Newberry, Percy E. (Percy Edward), 1869-1949 , London 1889, pp. 36.

DONATE

DONATE