Aesop's Fables: Moral Lessons Across the Ages

Aesop (c. 620–564 BCE, aged 44) was a legendary Greek fabulist and storyteller. About 400 of his stories have been preserved and now collectively known as Aesop's Fables. They were gathered across the centuries and in many languages in a storytelling tradition that continues to this day.

His fables were popularized and enhanced by Fedros (c. 20/15 BCE - 50 CE, aged c. 70) among the Romans, they served school uses, as then by the collection of Flavius Avianus (c. 4th-5th century CE).

Aesopus was also widely popular in the medieval and humanistic world, with various reductions, moralistic redesigns and adaptations.

Le Labyrinthe de Versailles. A painting shows entrance of the Versailles' labyrinth, with the statues of Cupid (left) and Aesop (right).

The labyrinth was a hedge maze in the Gardens of Versailles with groups of fountains and sculptures depicting Aesop's Fables. Water jets spurting from the animals mouths were conceived to give the impression of speech between the creatures. Each fountain was accompanied by a plaque on which the fable was printed, with verse written. It was from these plaques that Louis XIV's son learned to read. Citing repair and maintenance costs, Louis XVI ordered the labyrinth destroyed in 1778. In its place, an arboretum of exotic trees was planted as an English-styled garden.

His existence remains unclear. No writings by him survive. Some details of his life can be found in ancient sources, including:

- Aristotélēs (384-322 BCE, aged 62) indicated that Aesop was born around 620 BCE in the Greek colony of Mesembria.

- Hēródotos (c. 484 – c. 425 BCE, aged 61) told that Aesop was a slave in Samos; that his slave masters were first a man named Xanthus, and then a man named Iadmon; that he must eventually have been freed, since he argued as an advocate for a wealthy Samian; and that he met his end in the city of Delphi.

- Ploútarchos (c. 46 - c. 119 CE, aged c. 73) informed us that Aesop came to Delphi on a diplomatic mission from King Croesus of Lydia, that he insulted the Delphians, that he was sentenced to death on a trumped-up charge of temple theft, that met with Periander of Corinth, where Plutarch has him dining with the Seven Sages of Greece and sitting beside his friend Solon, whom he had met in Sardis, and then the Delphians, which suffered pestilence and famine, thrown Aesop from a cliff.

The archeological site in Midas City (Phrygia, Midas Şehri), midway between Eskişehir and Afyon, 8th-6th century BCE.

We know that Aesop was born in Phrygia, a historical region of central-western Anatolia, and lived as a slave in Samos in the 6th century BCE. He was already popular in Athens in the 5th century, and soon became a legendary figure.

The Greek sophist and rhetorician Himerius (c. 315 – c. 386 CE, aged 71) says that Aesop

was laughed at and made fun of, not because of some of his tales but on account of his looks and the sound of his voice.

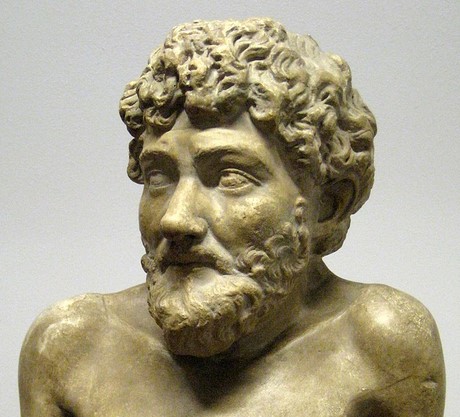

Plaster cast of a Hellenistic statue thought to depict Aesop; 4th century BCE, original in the Art Collection of the Villa Albani, Rome.

Aesop is described as a gobbler, a stammer, a strikingly ugly slave who by his cleverness acquires freedom and becomes an adviser to kings and city-states. He should travel to the East, to Babylon, to Egypt, then to Greece, especially to Delphi. The trips in Africa would explain the presence of camels, elephants and apes in the fables.

The motive behind his execution remains unclear. Despite this, his impact on literature, education, and culture is undeniable.

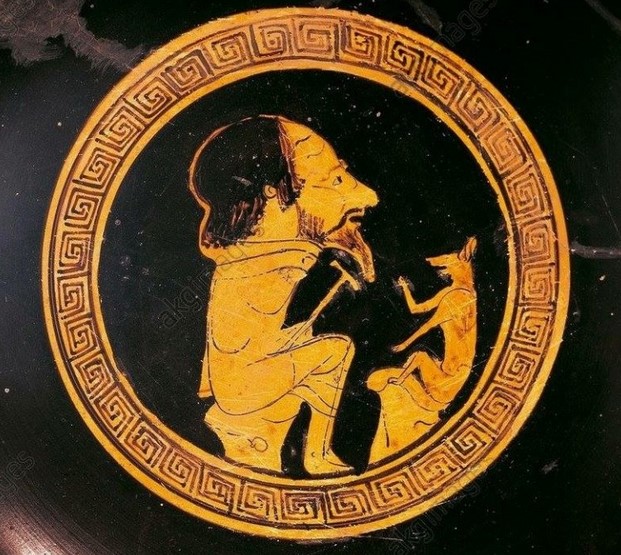

Image presumed to depict Aesop and fox, Greek red-figure kylix, c. 450 BCE.by a painter in Bologna 417 - ARV 916.183

Fairy tales are short and dry in style, and at the end they always have a brief moral. The characters in most fables are animals with human traits — talking, reasoning, and behaving according to exaggerated versions of our own instincts and flaws. There are also men or gods, while few are those fables with plants.

Curiously, these fables were often darker than their seemingly playful surface. The bluntness of the moral at the end of each story sometimes reflects a cynical view of human nature. For example, in The Scorpion and the Frog, the fable highlights an inescapable truth: some creatures — or by extension, people — are bound by their inherent nature, even if it leads to their own destruction. Such stories hold a mirror up to human tendencies, showing that despite reason and foresight, instinct and character often prevail.

Among Aesop’s most famous fables are:

- The Fox and the Grapes, from which the term "sour grapes" is derived. In this tale, the fox, unable to reach a cluster of grapes, convinces himself they are probably sour and not worth the effort — a timeless lesson in self-deception and rationalizing failure.

- The Tortoise and the Hare, a fable that has inspired countless adaptations, including Disney’s animated version. Its moral, “slow and steady wins the race,” emphasizes perseverance over arrogance and haste, a lesson with universal appeal.

- The Ant and the Grasshopper, where the grasshopper suffers through a cold winter due to his lack of preparation, while the ant thrives because of his hard work. This story, often interpreted as a warning about the consequences of idleness, emphasizes the value of foresight and diligence.

- The Scorpion and the Frog, offers one of the most vivid and timeless lessons in human nature. In this classic tale, a scorpion finds himself needing to cross a river but is unable to swim. Spotting a nearby frog, he politely asks for a ride on the frog's back. The frog, understandably cautious, hesitates. "What if you sting me?" he asks. The scorpion, seemingly reasonable, dismisses this fear with an argument that appears logical: "If I were to sting you, we would both drown. It wouldn’t make any sense for me to do that."

This fable conveys profound truths about instinct and character. No matter how compelling the reasoning or the circumstances, some creatures — and by extension, people — are governed by deep-rooted traits or instincts, often to their own detriment and that of others. The scorpion represents those who act destructively, even when it is against their own interests, illustrating that certain behaviors are hardwired and unchangeable.

This story has parallels in various cultures, with slight variations. In some versions, it's a turtle or a snake that plays the part of the scorpion, but the moral remains the same: the inevitability of certain behaviors.

Aesop’s enduring legacy can be seen not only in literature but also in art, theatre, and even modern cartoons. His fables, though centuries old, have been retold in every medium imaginable — proof of their timelessness and universal appeal. Despite the scant details about Aesop's life, his wisdom endures, continually shaping our understanding of morality and human nature through the stories we tell and the lessons we pass down from generation to generation.

Last update: September 30, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE