African religious traditions, a complex and diverse puzzle

African religious traditions showcase an impressive variety of beliefs, from the polytheism of ancient Egypt and Carthage to the ancestor worship prevalent across sub-Saharan Africa, and finally, to the sweeping changes brought by the spread of Islam. Each tradition reflects a deep connection between the spiritual and the material world, shaping the cultures and societies of Africa throughout history.

The ancient religious traditions of Africa, though varied and often regionally specific, provide a rich puzzle of beliefs, rituals, and cultural practices. Unfortunately, much of the contemporary written material has not survived, especially for sub-Saharan regions. However, we do have significant records from the ancient Egyptians, as well as descriptions by early travelers like Herodotus, who documented the religions and folklore of North Africa.

The Egyptian Pantheon: Gods, Kings, and Divine Rule

The religion of ancient Egypt is one of the most well-known African religious systems. Central to their belief was the idea that the pharaohs were not just rulers but descendants of gods, serving as their divine representatives on Earth. The Egyptian pantheon included many deities, each with distinct forms and powers, often represented in human-animal hybrids. Famous gods like Horus, the falcon-headed god of kingship, and Isis, the goddess of motherhood and magic, were central to the belief system.

Akhenaton and Nefertiti, Painted limestone. Paris, Louvre Museum

During the 18th Dynasty, Pharaoh Akhenaten (14th century BCE) attempted to radically shift Egyptian religious beliefs toward monotheism. He introduced the worship of the sun disc Aten as the one true god.

Aten is depicted as a solar disk whose rays end in hands, to show its creative and providential function. A limestone relief depicting the pharaoh Akhenaten, the queen Nefertiti and two princesses worshipping the Aten. 18th Dynasty, ca. 1353-1336 BCE, now housed at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

This move disrupted the established priesthood of Amun-Ra and led to significant social upheaval. To remedy this problem, Akhenaten relocated the capital to Tel el-Amarna and built temples dedicated to Aten. However, after his death — under mysterious circumstances — traditional religious practices were restored, with the old gods reclaiming their place. This restoration persisted until Egypt’s conquest by the Ptolemies in the fourth century BCE, which brought with it the influence of Greek deities, followed later by Roman gods when Egypt became part of the Roman Empire.

Akhenaten's experiment with monotheism is often seen as one of history's earliest attempts at religious reform. His focus on Aten was radical and short-lived, but it prefigures later monotheistic religions like Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Egyptian religious influence in Nubia, Meroë, and beyond

Egypt's religious ideas, especially concerning divine kingship and the worship of multiple deities, spread beyond its borders. In Nubia, particularly in Meroë (modern-day Sudan), there is archaeological evidence that the local population adopted many Egyptian gods. This influence likely extended to the Kingdom of Kush and beyond, with the city-state of Axum (modern-day Ethiopia) reflecting a mix of indigenous African and South Arabian religious practices.

In Axum, the adoption of South Arabian deities suggests early religious syncretism, blending local African beliefs with those brought over by traders and settlers from across the Red Sea. This points to the fluid nature of religious identity in ancient Africa, where external influences often merged with local traditions to create unique belief systems.

Statue of Molech, pagan Deity of Child Sacrifice, displayed at Colosseum, Rome

Carthage: the influence of Phoenician beliefs

In Carthage, which was founded by Phoenician colonists, many of the religious beliefs were carried over from the Phoenician homeland. The most notorious deity worshipped in Carthage was Molech, associated with fire and sometimes with human sacrifice. According to Roman sources, Molech demanded the sacrifice of children, and some historians believe that Hannibal's brother may have been sacrificed as a child to this deity.

A terracotta funerary urn containing the charred remains of an infant. The tophet of Carthage is a cemetery for infants in the ruins of the North African city of Carthage, now located in a suburb of Tunis. It was once located on the edge of ancient Carthage. The cemetery was used for over 600 years, between 730 BCE and 146 BCE, when was destroyed by the Romans.

The word tophet comes from the Hebrew topheth derived from "drum" or "place of burning," an open area for sacrifice. Archaeologists have uncovered numerous tophets (burial grounds) in the eastern Mediterranean region. The Tophet of Carthage, excavated between 1920 and 1970, shows burials of young infants, interred in small vaults with beads and amulets, and sometimes the bones of small animals. Low thrones or stones marked the early graves. These findings fueled debates about whether Carthaginian rituals involved large-scale child sacrifices or whether the graves were simply for children who died young from disease. The Carthage tophet has no adult graves, and many of the grave stelae are marked with dedications to Baal and Tanit, the patron deities of Carthage. Some researchers argue that these could be due to high infant mortality rather than ritual sacrifice. Carthaginian religion, like Egyptian religion, was dynamic and continued to evolve, particularly under Roman influence, when Roman gods and practices began to take hold.

Esie soapstone figures. In the sleepy Igbomina town of Esie, in Irepodun LGA Kwara State lays the first museum in Nigeria. The museum was established in 1945 to house one of the greatest treasures ever bequeathed to mankind, Esie Stone Images (Ere Esie). The Esie figures, over 800 stone carvings found in southwestern Nigeria, remain a mystery. Their purpose and origin are not fully understood, but they are thought to represent ancestors, gods, or notable individuals, highlighting the importance of sculpture in religious expression.

Sub-Saharan Africa: Ancestor Worship and the Spiritual World

In sub-Saharan Africa, much of what we know about early religious traditions comes from archaeological finds and oral traditions. In Nok (modern-day Nigeria), for example, carved terracotta figures suggest that the people may have revered deities or ancestor spirits. These stone statues bear resemblance to Mediterranean Mother Earth figures, though the more likely dominant belief system revolved around ancestor worship.

Ancestor veneration was central to many African societies. It was believed that the spirits of the dead continued to play an active role in the lives of the living, providing guidance, protection, and sometimes punishment. This practice is reflected in the Esie soapstone figures from southwest Nigeria and the brass heads from Ife, which may represent deified ancestors or important community leaders. Similarly, in Jenné-jeno, bones of deceased relatives were often buried within homes, suggesting a deep connection between the living and the dead.

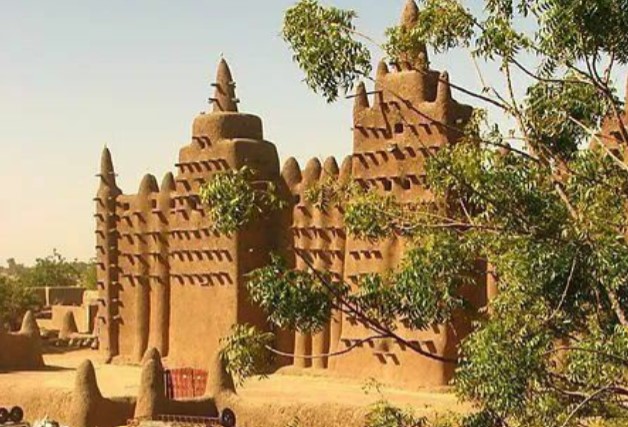

Islam’s influence on African architecture: the spread of Islam led to the construction of mudbrick mosques across West Africa, including the famous Great Mosque of Djenné in Mali. These structures combine Islamic principles with local building techniques, illustrating the syncretism of religious and cultural influences in Africa. Constructed by the community in 1906 on the remains of a pre-existing mosque, it is the largest historical mud mosque in the sub-Saharan region and is considered by many to be the greatest achievement of the Sudano-Sahelian architectural style. In 1988 the site was included in UNESCO’s World Heritage List, together with the entire Old City.

The Great Mosque of Djenné in Mali has been preserved till now thanks to the yearly community effort of maintenance coordinated by the barey-ton, the local corporation of traditional masons, holding technical capacities in earthen architecture but also considered to have magical powers.

The impact of Islam: a new religious paradigm

By the time Islam began spreading across North Africa in the 7th century CE, it brought significant changes to the religious landscape of Africa. Islam introduced monotheism to regions that had previously practiced polytheism or ancestor worship. In many areas, Islam blended with local traditions, giving rise to unique expressions of the faith. For example, while many Saharan and West African societies adopted Islamic customs, some continued to incorporate elements of their ancestral beliefs, especially in rituals related to life, death, and the afterlife.

Mosques became focal points of Islamic worship, and cemeteries were often established in mosque grounds or on city outskirts. The graves of holy men became revered as places of pilgrimage, much like ancestor veneration in earlier African traditions. While Islam transformed religious practices across Africa, in some regions, it coexisted with pre-Islamic customs, creating a hybrid spiritual tradition that remains in some places today.

Last update: September 30, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: