The rise and fall of the Akkadian Empire

In the central and northern areas of lower Mesopotamia, the Akkadians, a Semitic-speaking people, established a significant urban civilization. Prominent cities like Kish, Eshnunna, Sippar, Akkad (founded by Sargon), and later Babylon became the heart of this society. The Akkadians likely originated from the west, possibly migrating from the Syrian-Arabian steppes as pastoral tribes. Unlike mass migrations, their movement was more of a slow and steady infiltration into the region in small tribal and family units.

The Akkadian Empire, the first known empire in Mesopotamia, was established in the city of Akkad and flourished from the late 24th century BCE to the early 22nd century BCE. The Sumerian dominance over the region lasted for about a century before a new conqueror, Sargon the Great (2334-2279 BCE), took power. According to the Legend, which draws upon his illegitimate birth, Sargon was placed in a reed basket in the Euphrates before he was drawn out by a man named Aqqi and raised as a gardener. After this humble beginning Sargon establishes himself as the king of the first Mesopotamian empire.

Map of the Near East showing the extent of the Akkadian Empire and the general area in which Akkad was located

Sargon's conquests and the foundation of Akkad

Around 2350 BCE, Sargon, a semitic official in the city of Kish, overthrew the ruling Sumerian dynasty and laid the foundations for what would become the Akkadian Empire. The exact location of Kish remains unidentified but is thought to be near modern-day Baghdad. Unlike the fragmented territorial nature of the Sumerian states, Sargon envisioned a unified empire extending over known Mesopotamia and beyond, from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean and from the Iranian mountains to the Arabian desert.

Sargon’s rule was marked by relentless military campaigns rather than a unified administration. He conquered the Sumerian cities in the south and launched expeditions to bring regions like Kurdistan, Syria, and Elam under his influence, primarily for commercial dominance. His empire was held together by a network of loyalty-based tribal alliances rather than a centralized bureaucratic system.

Sargon, originally from the Akkadian people—nomadic shepherds who spoke a Semitic language—eventually integrated into the Mesopotamian cities, leading to a bilingual society. He defeated Lugalzagesi, the powerful Sumerian king of Uruk, and expanded his empire by subjugating or destroying other Sumerian and Syrian cities. Sargon's empire extended from the Lebanese mountains to the Taurus mountains in Anatolia ("to the Cedar Forest and the Silver Mountains," as the sources say), marking the first centralized empire in Mesopotamian history.

The Akkadian Empire under successors and its decline

After Sargon's death, the Akkadian Empire lasted less than a century. His sons Rimush (2278-2270 BCE) and Manishtushu (2269-2255 BCE) successfully maintained the empire by suppressing revolts and leading campaigns from northern Syria to western Iran.

Naram-Sin (2254-2218 BCE), Sargon’s grandson, brought the empire to its peak, controlling territories from eastern Turkey to western Iran, reaching as far as Ebla in Syria and Elam in present-day Iran. Naram-Sin’s ambitions led to an empire that stretched "from sea to sea," covering lands from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf, solidifying the concept of a political and commercial empire on a grand scale.

Unlike Sargon, who was deified posthumously, Naram-Sin declared himself a god during his lifetime. He introduced the practice of royal divinization, proclaiming himself a god during his lifetime. This move was a significant shift in Mesopotamian political ideology, which emphasized the divine right of kings and the ruler’s role as a mediator between the gods and humanity.

The reign of Shar-kali-sharri (2217-2193 BCE) was marked by prosperity, but by the end of his rule, the empire had shrunk significantly. After his death, the Akkadian Empire experienced political instability until Dudu (2189-2169 BCE) and Shu-Durul (2168-2154 BCE) restored some order, though they ruled more as city-state leaders than as emperors.

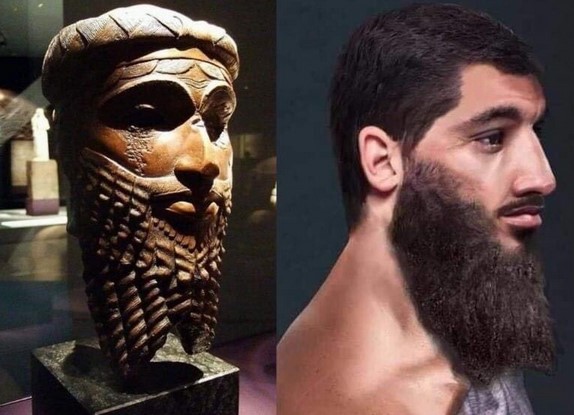

Bronze head of a king of the Old Akkadian dynasty, most likely representing either Naram-Sin or Sargon of Akkad. Unearthed in Nineveh (now in Iraq). In the National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad. Height 30.5 cm.

The fall of the Akkadian Empire

The empire ultimately collapsed due to internal rebellions, rivalry for the throne, and external pressures from groups like the Gutians, who were depicted as barbaric invaders in Sumerian literature. In "The Curse of Akkad," which laments the empire's destruction by the Gutians, this people is portrayed as inhuman and bestial: "The Gutians, a people who know no restraints; with human instincts but the intelligence of a dog and the face of a monkey. The god Enlil made them come out of the mountains, like swarms of locusts overrunning the land."

In the legend "The Marriage of Martu," the name used by the Sumerians for the god Amurru and his people, the Amorites, the friends of the princess who is about to marry the god warn her against the barbarism of his people: "The Martu who know no grain... The Martu who know no houses or cities, the primitives of the mountains... one who dwells in a tent, in wind and rain, does not pray, lives in the mountains, knows not the houses of the gods... the Martu who digs up tubers, who does not bend the knee to cultivate, who eats raw meat, who has no house in life and is not buried after death." Yet, except for the Gutians, all these other nomadic peoples who immigrated into Mesopotamia eventually assimilated into urban civilization, becoming its defenders against subsequent waves of nomadic invasions.

Other invading groups, including the Elamites, Lullubi, Hurrians, and Amorites, also contributed to the empire's downfall. This period led to a resurgence of Sumerian city-states and initiated the Neo-Sumerian period, during which cities like Ur regained prominence.

The Akkadian legacy and Royal ideology

The Akkadian Empire set a precedent for future Mesopotamian kings over the next two millennia. Akkadian rulers were seen as divinely favored, serving as earthly representatives of the gods. Sargon claimed titles such as "representative of Ishtar," "anointed of Anu," and "great ensi of Enlil," linking his rule to divine favor. The image of the conquering king, ruthless toward enemies, became central to Mesopotamian ideology.

Kings boasted of the piles of corpses they left in their wake and the cruelty with which they treated defeated enemies. Sargon the Great, after defeating and capturing Lugalzagesi, king of Uruk, bragged of leading him to the temple of the god Enlil "with a dog collar around his neck."

Women and Royal power

Women, especially in royal families, had significant roles in Akkadian society. Royal women could participate in administration, manage provincial affairs, and serve as priestesses in major temples. Sargon's daughter, Enheduanna (23rd century BCE), a priestess, wrote religious hymns that have survived to this day, where she speaks to the gods in the first person, making her considered the earliest known poet in history.

Economic organization and State control

The Akkadian economy was largely state-controlled, with most land owned by the king or temples. Slaves, artisans, soldiers, and officials were maintained through public rations, while private ownership of land was limited. The empire’s economic system required meticulous planning, leading to the development of advanced administrative and accounting practices.

Under the "kings of Sumer and Akkad," private economic activity existed, and individuals were allowed to own land and make it productive. However, private property was generally limited: much of the land belonged to the king or the temples, and much of the produce flowed into the palace. Slaves and deported individuals forced into labor and sustained through state-provided barley, oil, and wool rations made up a significant part of the population, but artisans, soldiers, and officials also received public rations according to their rank. Sargon of Akkad boasted in an inscription that "5,400 men ate daily in his presence." Officials and soldiers also received land grants in usufruct, which they could not sell and were cultivated through forced labor.

The role of the king was not only to exploit collective labor, gather taxes and tributes, and lead successful wars of conquest by annihilating or enslaving enemies. The poems praising Sumerian and Akkadian kings also highlight their achievements as builders: the temples, palaces, and walls they constructed, and especially the canals they ordered to be dug, used for both irrigation and communication. They transformed uncultivated lands into fertile fields, drained swamps to make them arable, and established new farming settlements. As a result, Mesopotamia developed a highly regimented society with a centrally controlled economy, which today we would call a state-run or planned economy.

To manage this planned economy, highly sophisticated accounting methods were developed. The royal scribes worked to predict the growth rates of herds and flocks, estimate the number of women needed to grind the grains stored in the granaries or spin yarn in the weaving workshops, and calculate the number of rations required to support them. They also determined how many bricks were needed for each construction site and the labor required to make them, as well as the amount of grain and livestock that each province was obligated to pay in taxes. Royal merchants had to account for all their transactions, ensuring that their books were balanced.

These extensive controls required a large number of specialized personnel. Therefore, the kings, like the temples before them, established schools to train scribes. These scribes were not just individuals who could read and write; they formed the backbone of both the state and religious bureaucracies.

Cultural and literary contributions

The Akkadian Empire's influence extended beyond its political and military achievements, inspiring a rich tradition of literature. Stories like the "Curse of Akkad" and legends surrounding Sargon and Naram-Sin reflect the complex relationship between rulers and the divine. These narratives portrayed Sargon as a hero while often depicting Naram-Sin as disrespectful toward the gods, leading to his downfall.

The legacy of the Akkadian Empire continued to shape Mesopotamian civilization, setting standards for governance, culture, and royal ideology for centuries to come. Gradually, Akkadian (an East Semitic language) replaced Sumerian (a non-Semitic language) in administrative documents.

Dating by year names, that is naming each year after a particular event such as “the year Sargon destroyed Mari,” became the system used in Babylonia.

Last update: October 15, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: