The Ancient City of Akko: From Phoenicians to Crusaders

Known in biblical times as Akko (Akkon in Western medieval chronicles), it was an ancient maritime center during the second and first millennia BCE, significant not only regionally but also internationally.

Until 1954, the only evidence of its existence was its coins. Pre-Hellenistic coins depicted local motifs (a galley, images of deities, portraits of rulers); Hellenistic coins featured Tyche (the Greek goddess personifying fortune) alongside Hellenistic cities, while Roman coins portrayed emperors and temples.

About 20 years later, archaeological excavations unearthed the ancient city 16 km northeast of Haifa, between Tyre to the north and Dor, Jaffa, Ashkelon, and Gaza to the south.

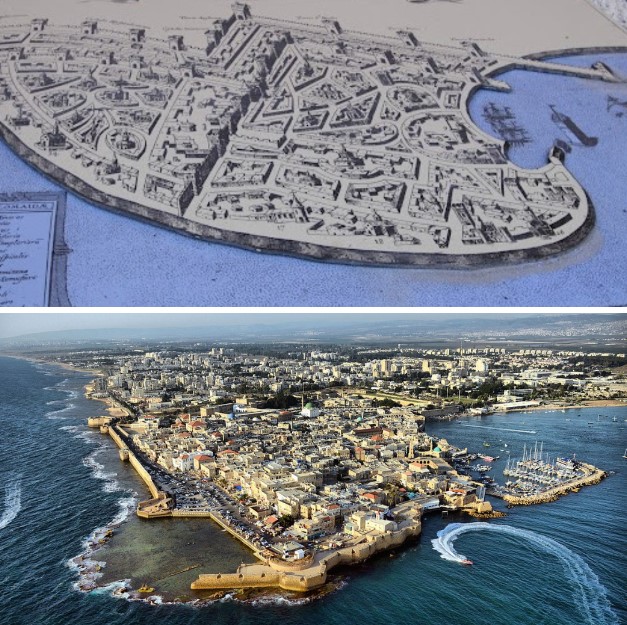

Akko, view of the old city (peninsula)

Although today the archaeological site lies about 700 meters inland from the sea, Akko was originally a peninsula flanked by the Mediterranean Sea to the west and the estuary of the Na’aman River (Belus) to the south. It was one of the few natural harbors along the southern Levantine coast suitable for anchoring.

Akko was the principal port city of the region for much of its 5,000-year history. It was consistently valuable to the fleets of kingdoms and empires competing for it, serving as the main harbor for the entire southern Levant. It held special importance for maritime trade between Egypt and Syria, as ships required anchorages and intermediary ports between the two kingdoms.

Until modern times, its history was more complex and tumultuous than other cities due to its strategic location. Few urban centers have experienced a history as dynamic as Akko's, marked by wars, sieges, and destructions; various rulers, each introducing new knowledge and ideas.

Akko

The earliest settlement discovered dates to around 3000 BCE but appears to have been abandoned after a few centuries, possibly due to flooding of surrounding farmland by the Mediterranean.

The area was repopulated between 2000 and 1550 BCE by the Phoenicians, who founded Akko. Since then, it has been continuously inhabited.

Some testimonies confirm its existence:

- Egyptian execration texts record a ruler in the 18th century BCE named Tūra-ʿAmmu.

- In the Late Bronze Age, the city was listed as Aak among the conquests of Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III.

- During c.1350 BCE, the Amarna Period (named after Tell el-Amarna, the site of Akhetaten, the Egyptian city founded by Pharaoh Amenhotep III), there were uprisings in Egypt's Levantine provinces. The Amarna Archive contains letters about the ruler of Akko. In one, King Biridiya of Megiddo complains to Akhenaten about the king of city, accusing him of treason for releasing Hapiru king Labaya of Shechem instead of handing him over to Egypt.

- Archaeological excavations show that:

- during Late Bronze Age, the city had pottery, metal, and other commercial industries;

- during Iron Age

- the settlement continued its traditions and maintained contact with Cyprus and the Shardana - a group of "Sea Peoples" mentioned in the Egyptian Onomasticon of Amenope (dating from the late 20th to the 22nd Dynasty).

- Industrial production dominated Tel Akko at the end of the second and the first millennium BCE. A bronze-working and pottery production area from the 13th-12th century BCE was discovered and continued operating into the Persian period (6th-4th centuries BCE) under Achaemenid patronage.

- Assyrian records indicate Akko was a Phoenician city—though Josephus claimed it was part of Solomon's Kingdom of Israel. Around 725 BCE, it joined Sidon and Tyre in a revolt against Neo-Assyrian Emperor Shalmaneser V. An evident destruction layer in the ruins, likely dating to the 7th century BCE, supports this.

Thus, Akko was an important port city on the Canaanite coast in the ancient region of Phoenicia. But, who were the Phoenicians?

The Phoenicians were a Semitic-speaking people from the Syrian and Palestinian coasts. They were pirates, artisans, and merchants, but above all, the greatest navigators of the ancient world. Many important nautical inventions are credited to them. They built the best ships of the time from cedarwood grown in their forests.

From the 13th century BCE, due to upheavals caused by the Sea Peoples, the Phoenicians concentrated on maritime activities. They did not conquer territories but established trade bases along their routes. These served as ports where they unloaded goods, loaded others, and acquired raw materials they lacked. Their craftsmanship was high-quality and highly sought after.

By studying Mediterranean currents and wind patterns, they established two major routes: one east-west for outbound journeys and another for return trips. From Tyre to the Strait of Gibraltar it took about 80 days: you started from the nearby islands of Cyprus and Rhodes, crossed the Ionian Sea to reach Sicily, then reached southern Sardinia, the Balearic Islands, the Spanish coast and finally the strait. The return was made by going along the coast of Africa.

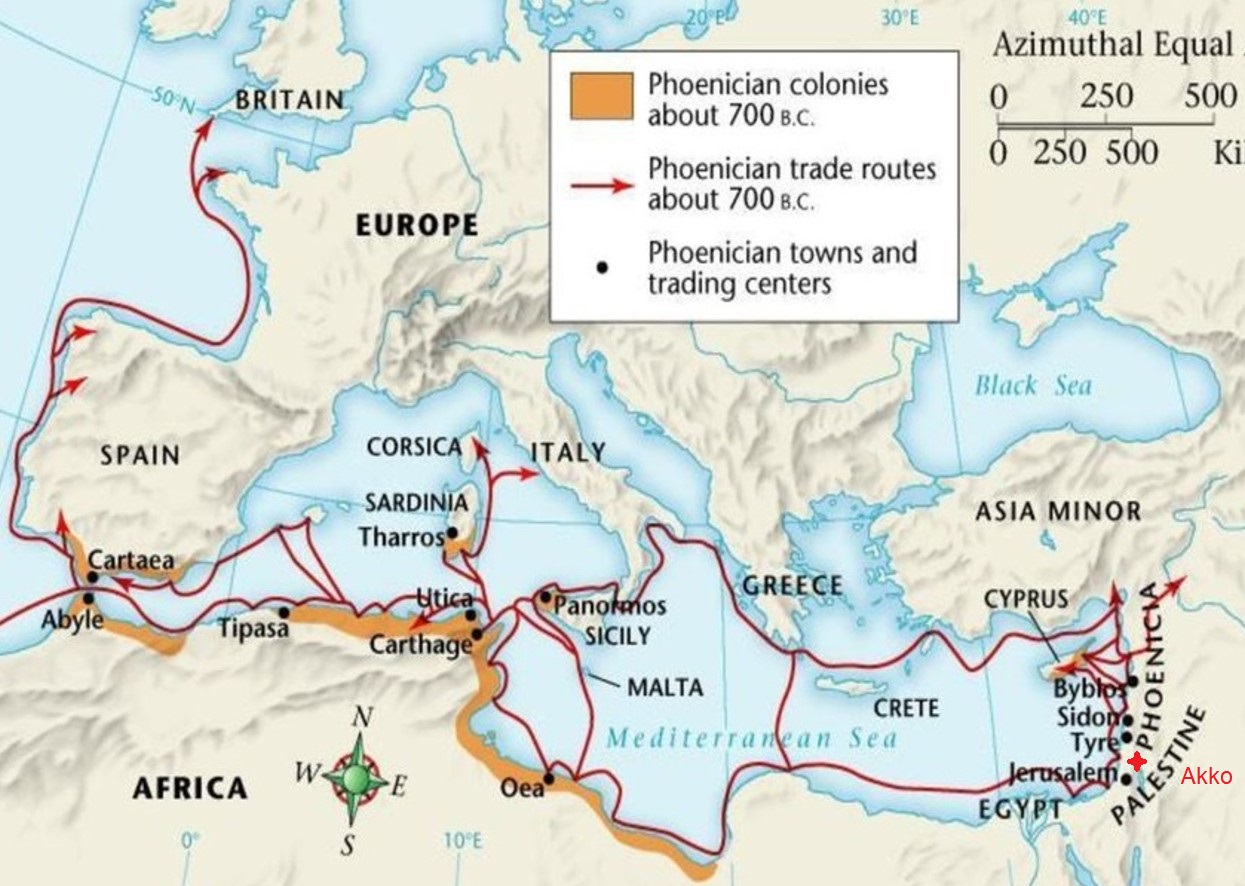

Map of Phoenician cities

During the 9th-8th centuries BCE, Phoenician trading posts on Mediterranean coasts became colonies. By 600 BCE, following the end of their colonization phase, they explored beyond the Mediterranean to find new routes and raw materials.

Cities like Akko, often situated on promontories, enabled the creation of two ports, one to the north and another to the south, used depending on winds and seasons. Politically autonomous, they shared traditions and gods.

The Phoenicians built an extensive commercial empire by the 1st millennium BCE, extending across the Mediterranean.

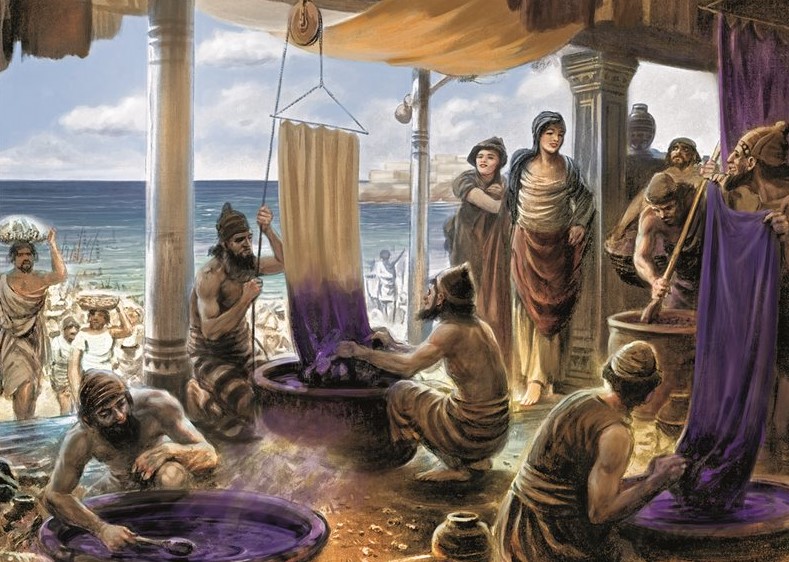

Production of the famous tincture in a Phoenician centre located near the sea

The Greeks called them Phoinixes, which means '(those) red purple', because of the excellent linen and wool fabrics colored with purple. Their wealth came largely from purple dye, extracted from mollusks and valued like gold. Akko became a major center for processing this dye.

Purple dyed fabric with their corresponding sea snail - Exhibit of the Museum of Natural History in Vienna.

During the Persian era, Akko was part of Tyre’s territory and became one of the Persian Empire's key ports. Strabo noted its significance in campaigns against Egypt. Cambyses II used the region as a staging area for his invasion of Egypt. The Persians expanded the city to the west and probably improved its port and defenses. Archaeologists unearthed the remains of a Persian military outpost that may have played a role in the successful Achaemenid invasion of Egypt in 525 BCE. The industrial production of the city continued until the late Persian era, with iron factories particularly expanded.

Greek historians refer to the city as Ake, meaning "cure." According to the Greek myth, Heracles found curative herbs here to heal his wounds. Josephus calls it Akre.

In the 4th century BCE, after probably settling an Athenian merchant colony, Alexander the Great granted it independence and the right to mint coins. During his campaign to drive the Achaemenids from the Levant, the fortifications of the Persian period were heavily damaged. The name of Akko was changed to Antiochia Ptolemais.

After the death of Alexander, his main generals divided his empire, Akko was ruled by the Egyptian Ptolemies. Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246 BCE) granted it a full town constitution and renamed it shortly Ptolemais, in honor of his father in 260 BCE.

The name was kept until the Byzantine era and on the last town coins minted in 256 CE. The city became the capital of the region and its importance increased.

A tetradrachm of Ptolemy III minted in Akko

Ptolemy minted silver coins in the city from 253 BCE. The head of Ptolemy I appears on the obverse while the reverse carries the Greek inscription "of king Ptolemy" and an Egyptian eagle standing on a thunderbolt providing the coin with validity and authority. The mint was run directly by the Ptolemaic administration. It is important to point out that the Ptolemaic kings instituted a closed monetary area in all the places they governed, an area that had a different standard and weight than elsewhere. Ptolemaic minting in Akko continued until the days of Ptolemy V.

After the battle of Paneion (Paneas) in 200 BCE, Antiochus III conquered the city for the Syrian Seleucids. At the end of 170 or the beginning of 160 BC, Antiochus IV (Epiphanes) founded a Greek colony in the city, which he named Antioch in his honor. During his reign the Hasmonean revolt broke out.

About 165 BCE Judas Maccabeus defeated the Seleucids in several battles in Galilee and drove them to Antioch.

A bronze of Antiochus IV

In that period royal Seleucid coins from Antioch were the currency in Akko but small bronzes were minted too. Seleucus IV continued minting in Akko, while his successor, Antiochus IV (Epiphanes) minted large amounts of small bronze coins in Akko as well as silver coins. In fact, this was a quasi-autonomous issue.

In addition to minting Seleucid coins in Antioch, in the middle of the second century BCE the Seleucids allowed the minting of almost autonomous coins of bronze and silver with the King's portrait at the rest of the port cities in the Land of Israel, in Jaffa, Ashkelon and Gaza. The coins from Akko coins bear the inscription "Of the Antiochenes in Ptolemais". For silver, the Seleucids used the Phoenician weight standard in the mint of Akko, continuing the Ptolemaic weight system.

Around 153 BCE, Alexander Bala, son of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, contending for the Seleucid crown with Demetrius, took possession of the city, which opened its doors to him. Demetrius offered many bribes to the Maccabees in order to gain Jewish support against his rival, including the income of Ptolemais for the benefit of the Temple of Jerusalem, but in vain. Jonathan Apphus joined Alexander; Alexander and Demetrius met in battle, and the latter was killed. In 150 BCE, Alexander received Jonathan with great honors at Ptolemais. But some years later, Tryphon, an officer of the Seleucid empire who had begun to suspect the Maccabees, lured Jonathan to Ptolemais and there made him a prisoner by treachery.

The city was conquered by Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BCE), Tigranes the Great (95-55 BCE) and Cleopatra (51-30 BCE). Here Herod the Great (r. 37-4 BCE) built a gymnasium.

An Attic weight tetradrachm of Antiochus VIII

There were two monetary zones in the Seleucid Kingdom; one according to the Attic standard and the other according to the Phoenician. Attic weight silver was minted Akko, but the coin finds show that these were minted for the northern Seleucid regions and not for local use.

Most of the Seleucid coins in Akko were minted by Antiochus IV, Demetrius II, Antiochus VIII and Antiochus XII. Towards the end of the Seleucid period, when the kingdom started to crumble and the central administration weakened, different areas of the kingdom made independent moves. Autonomous minting in Akko increased from about132 BCE, taking advantage of the political situation of the kingdom.

The Seleucid kingdom gradually withdrew from the political arena and the Romans, during whose reign Antioch was a large port city with autonomous authority, became the dominant power. In Roman times, the importance of its port was equivalent to that of Caesarea. The maritime connection between Judea and Rome was through it, whose inhabitants were still Phoenicians and Greeks.

The city was renamed Ptolemais in 48 BCE and the following year Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) visited it.

Under Augustus (63 BCE-14 CE) a gymnasium was built.

In 4 BCE, the Roman proconsul Publius Quintilio Varo assembled his army there to suppress the revolts that had broken out in the region following the death of Herod the Great.

Around 37 BCE, the Romans conquered the Hellenized Phoenician port city called Akko. With the emperor Claudius, it became a colony in southern Roman Phoenicia, called in short Claudia Ptolemais (Colonia Claudia Felix Ptolemais Garmanica Stabilis). He rebuilt the city and renovated its port; its residents became Roman citizens and were exempt from taxes. The veterans of the Roman army also settled in the colony, which was one of four with Berytus, Aelia Capitolina and Caesarea Marittima, created in the ancient Levant by the Roman emperors for the veterans.

According to Josephus, at the outbreak of the Jewish revolt against the Romans, the Greek residents of the city murdered about 2,000 Jews. The city served as a base for the Roman legions that were brought there to suppress the Jewish revolt.

During the Great Jewish Revolt (66-73 CE), Claudia Ptolemais served also as a starting point for the campaigns of Cestius and Vespasian to suppress the revolt in Judea.

A coin commemorating the establishment of the colonia Ptolemais minted under Nero

Roman colonies used Latin as the official language, so now coins with Latin inscriptions were minted in the city. Inscriptions on coins of other cities were in Greek. For example, one of the coins minted under Nero (about 53 CE) shows the emperor ploughing the city borders with a plow harnessed to a pair of oxen in a ceremony called pomerium, a symbol for the establishment of a new colony. The coin bears the inscription Colonia Ptolemais. The plaques on the standards bear the numbers of the four Roman legions based in Judaea: III, VI, X, XII. Some of these legions are mentioned in the writings of Flavius Josephus as taking active part in the Jewish war Galilee between the years 66–68 CE.

Hadrian (76-138 CE) rebuilt the colony of Akko-Ptolemais and the city grew to over 20,000 inhabitants. It was a centre of Romanization in the region, but most of the population was made up of local Phoenicians and Jews: therefore, after the time of Hadrian, the descendants of the first Roman settlers no longer spoke Latin and had fully assimilated in less than two centuries (however, the customs of local society were Roman).

A coin from the reign of Trajan with the name of the colony.

After suppressing the revolt in Galilee (66–67 CE), the Greeks celebrated their victory in Akko. During the revolt there was an increase in minting in Greece and in other cities. It is possible that the reason was the arrival of a number of Roman legions and the need for large sums of money to finance their upkeep. The Romans utilized the local currency of city coins.

The Acts of the Christian Apostles describe the evangelist Luke, the apostle Paul and their companions spending a day in Ptolemais with their Christian brothers.

Akko became an important Roman colony. Roman settlers were transferred there from Italy thus greatly increasing the control of the region by the Romans in the following century.

A tetradrachm of Caracalla. The Akko's mintmark is the caps of the Dioscuri.

Hadrian rebuilt the colony of Akko-Ptolemais and minted a similar, undated "founder coin". The change is in the standards of the Roman legions that were active in Judaea at that time. This indicates the expansion of the colony's boundary or its shift to another part of town, such as expanding the area of the port, or expansion of the public areas. The coin was minted at the time of the Bar-Kokhba revolt (132–135 CE). Simultaneously Hadrian minted a large issue of a similar coin in Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem) that depicts the founding of the colony Aelia Capitolina on the ruins of Jerusalem. At the same time Hadrian issued a coin that marked the founding of Caesarea.

Numerous coins were minted during the Roman period in Akko, amongst which were coins with special types. Three exceptionally interesting coins were minted under Elagabal (218–222 CE): one shows the acropolis, the city's fortress, and another unique coin that shows the port with a ship in it as seen from the sea. The third coin is features the zodiac. Most of the coins minted under the Romans in Akko were bronze but for a short period silver provincial tetradrachms were minted under Caracalla, showing the relative importance of Akko. The obverse shows the emperor, while the reverse an eagle.

It is unclear whether municipal coin minting was under Roman supervision or done entirely by the city authorities. It is noteworthy that minting of silver was limited by the amount of silver metal in the hands of the issuer, whereas with bronze coins large issues could have diminished their value and their purchasing power.

In the middle of the third century, under Gallienus (in 256 CE to be precise), minting ceased in Akko which was the last city to mint municipal coins. The inferior imperial silver antoniniani entered into circulation. In the Byzantine era no coins were minted in Akko.

Under Byzantium, its importance waned, and by the 7th century CE, it had shrunk to a small settlement. Ptolemais remained Roman for almost seven centuries until it was conquered by the Arabs in 638 CE. Akka fell to the Rashidun Caliphate, marking the beginning of Arabs rule. The city was revitalized as a major port under the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates. Umayyad caliph Muawiyah I fortified Akko and utilized its shipyards for naval campaigns against the Byzantine Empire.

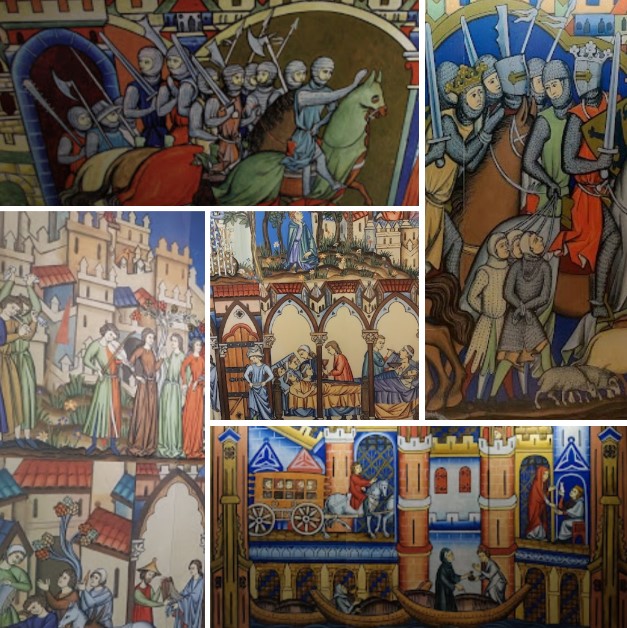

Akko during Crusades period

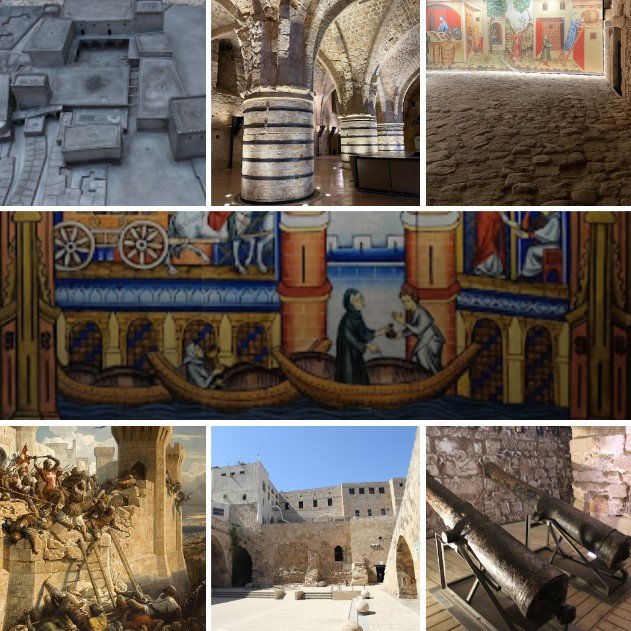

The Crusades brought a new era of transformation. In 1104, Akko was conquered by Crusaders, becoming their primary port and a key stronghold in the Holy Land. The city prospered as a hub of trade and cultural exchange, particularly in the lucrative spice trade. Divided into quarters based on origins and military orders, its population peaked at 50,000. Crusader-era structures, such as the Knights’ Halls and the Templar Tunnel, remain well-preserved, providing glimpses into this period of history.

The city’s strategic importance made it a focal point during the Third Crusade. In 1191, Richard the Lionheart and Philip II of France recaptured Akko, which became the capital of the Crusader kingdom. However, internal conflicts among the Crusaders and external threats from Muslim forces eventually led to its decline.

After the fall of Jerusalem, it was the Crusaders' last bastion until it fell to Sultan al-Ashraf in 1291.

Crusader imitation of a Fatimid dinar

Shortly after the third Crusade (1191), large quantities of bronze coins were minted in ‘Akko with the inscription Accon. ‘Akko minted mainly two kinds of coins during the Crusader period. There were imitations of Muslim coins, including gold bezants, as well as western European denier types made of billon. The bronze pougeoise minted in ‘Akko shows a fleur de lys, the emblem of the French royal house of Borbon.

The gold bezants imitated the dinars of caliph El-Amir from the twelfth century and were used in trade for big transcations. These imitative issues facilitated trade and economic activity between the two populations of Franks and Muslims and were minted in Jerusalem too in the twelfth century. Initially they carried an original Islamic formula, but after the Pope's representative visited ‘Akko and expressed the pope’s concern, the legend was changed to an inscription in Arabic mentioning ‘the father, son and Holy spirit’ and a cross was added too.

The local merchants in ‘Akko who originated in Venice, Pisa, Genoa also minted small value lead tokens of lead in order to pay the local population for goods and services. With the capture of ‘Akko by the Mamluk sultan al-Ashraf Khalil on May 18, 1291, coin minting in ‘Akko ceased. Moreover, the city ceased to exist for the next 450 years.

In 1291, Akko fell to the Mamluks after a protracted siege. The Mamluks systematically destroyed the city to prevent its future use by Crusaders. Akko remained in ruins for centuries, its former glory immortalized in regional folklore.

The bloody siege of Acre in 1291, led by the Mamluks of Sultan al-Malik al-Ashraf Khalīl

Akko’s fortunes revived under Ottoman rule in the 16th century. By the late 18th century, leaders like Zahir al-Umar and Jazzar Pasha transformed it into a thriving port and regional capital. They reconstructed fortifications and established Akko as a center of commerce and governance.

During Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign in the Levant, Akko withstood a siege in 1799, marking a pivotal moment in its history. The city’s resilience under Jazzar Pasha earned it renown as a symbol of defiance.

Today, Akko is a picturesque Israeli town, location for steel and glass industries as at the Phoenician era. Imposing walls from the early 19th century separate the old city dating back to the Ottoman period, today inhabited mainly by the Arab population, from the new one, where lives instead mostly the Jewish population.

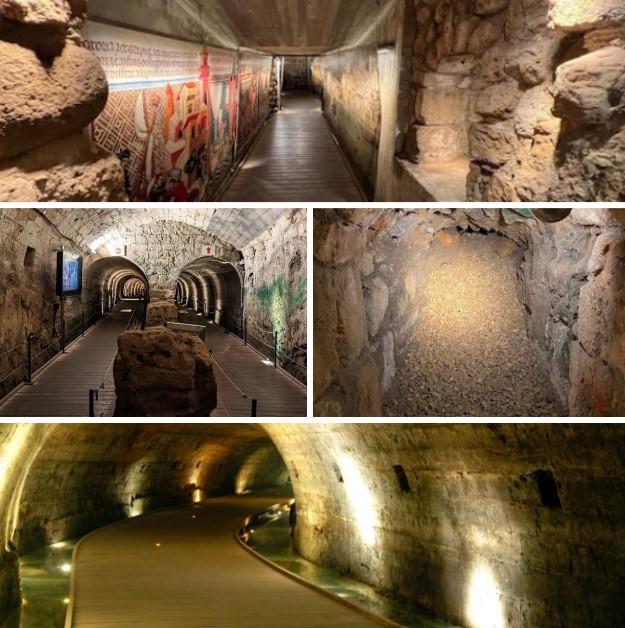

Below is the underground city dating back to the time of the crusades.

The Hospitaller Fortress

The latter offers more than a few traces of the buildings built by the 'Knights Hospitaller' and the 'Templars', the two military monastic orders that were responsible respectively for caring for the sick and protecting pilgrims in the Holy Land.

You can still admire the so-called 'Halls of the Knights' dating from the second crusade, that is to say the time when the Christians lost Jerusalem and had to transfer their kingdom elsewhere on the coast. It was then that the knights moved their headquarters to Akko, where they also had possessions from the time of the first crusade. They expanded what was already there, expanding in all directions, and thus building what is now called "the city below". It is very well preserved.

The 350-metre long Templar Tunnel, discovered in 1994 and built to connect the Templars' fortress to the port, is remarkable.

Akko, Israel. This tunnel 350m long, was was discovered in 1994 and constructed by the Knights Templar to serve as a strategic underground passageway linking the fortress with the port.

Last update: November 19, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: