Arameans, a cultural and political legacy in the Ancient Near East

The Arameans were significant not just for their political presence in ancient Syria, Mesopotamia, and Babylon, but also for their role in spreading the Aramaic language and their adaptation to the cultural environment of their time. While they left a substantial linguistic legacy, their artistic and cultural contributions were more of a synthesis of influences from surrounding civilizations rather than entirely original creations. Their legacy is better understood as part of the larger cultural and historical fabric of the ancient Near East, particularly the North Syrian and Mesopotamian regions.

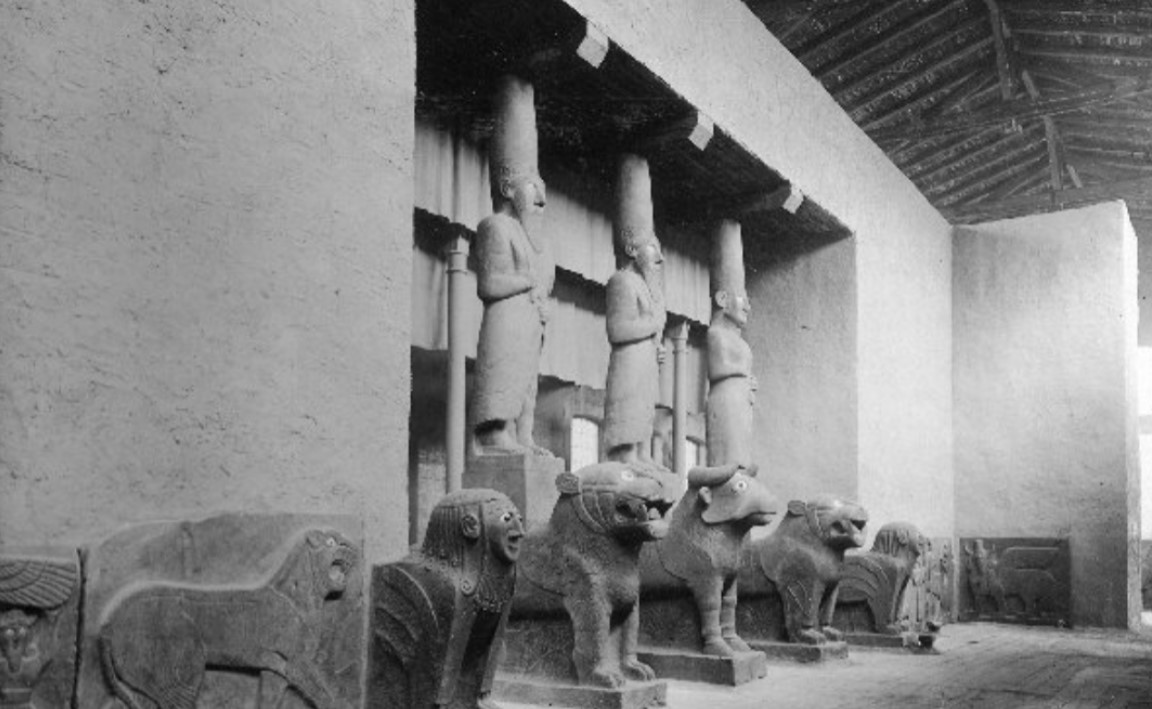

Some finds in the archaeological site of Tell Halaf

The Arameans were one of the ethnic and linguistic groups of the Semitic peoples. They were traditionally believed to be descendants of two individuals named Aram: the fifth son of Shem (son of Noah) and a son of Kemuel, the nephew of Nahor, Abraham’s brother. These figures were considered the eponymous ancestors of the Arameans.

Early History

The first references to the Arameans date back to the early 2nd millennium BCE. Their presence became more noticeable around the 12th century BCE when they began migrating from the steppes of Mesopotamia, located between the upper courses of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, into northern Mesopotamia. The Old Testament also suggests that the Arameans were nomads in the eastern regions of Syria and Palestine during this time, eventually spreading westward into Syria and Palestine, and eastward into Assyria and Babylon, where they left a lasting influence on local languages and culture.

Political Expansion

In Syria, the Arameans established several small states, with Damascus being the most significant. In Babylon, the Neo-Babylonian or Chaldean dynasty was of Aramean origin. Archaeological evidence from sites like Tell Halaf (ancient Guzana) and Zincirli (ancient Sam'al) reveals that their palaces followed architectural models similar to those used by Assyrian kings. These structures, known as "bīt hīlani," often featured a throne room preceded by a large portico topped with an upper floor. Their buildings were richly decorated with bas-relief sculptures, frequently depicting lions and mythical creatures, influenced by Hittite artistry.

Language and Cultural Influence

The Aramaic language became a widespread lingua franca across the ancient Near East, heavily influencing other Semitic languages such as Hebrew. It eventually lost its dominance with the rise of Arabic. Aramaic dialects diversified into regional variations, such as:

- Palestinian Aramaic (including Judean, Galilean—the language of Jesus—and Samaritan Aramaic)

- Syrian Aramaic (Nabataean and Palmyrene dialects)

- Mesopotamian Aramaic (Syriac, which became the literary language of Christian Arameans)

- Southern Mesopotamian Aramaic (Babylonian Talmudic Aramaic and Mandaic)

Aramaic script, derived from ancient Phoenician, influenced the development of other writing systems, including Arabic, Hebrew square script, and scripts of other Semitic and non-Semitic peoples.

Decline and Cultural Adaptation

The Arameans reached their peak politically during the decline of the Assyrian Empire after the death of Tiglath-Pileser I in 1074 BCE. During this period, they managed to establish independent political entities in Upper Syria, northern Mesopotamia, and Babylon. However, as Assyria regained power under rulers like Ashshur-dan II and later Shalmaneser III, the Aramean states faced increased pressure and eventually succumbed to Assyrian dominance.

Despite their political decline in regions like Mesopotamia and Syria, the Arameans managed to establish significant influence in Babylon, where they formed the last Neo-Babylonian dynasty of Chaldean origin.

Artistic Contributions

The artistic contributions of the Arameans have been challenging to define precisely due to the complex interplay of influences from surrounding cultures. The artistic styles found in sites like Tell Halaf, Zincirli, Hama, and Damascus indicate that Aramean art was a blend of various elements, including Hittite, Hurrian, Assyrian, Phoenician, and Egyptian motifs. This mix created an art form that lacked a distinctive, original style, often perceived as imitative of the surrounding cultures.

One notable convention attributed to the Arameans is their depiction of male figures with clean-shaven lips, though this feature was not consistently applied. In architecture, efforts to identify a purely Aramean element have been largely unsuccessful. For example, theories suggesting that the Arameans introduced South Arabian architectural models to Upper Syria and Urartu have been contested due to a lack of historical continuity.

The Neo-Hittite or Syro-Hittite Artistic Tradition

The rise of artistic expression in Upper Syria at the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE coincided with the political ascendancy of the Arameans. This artistic style, known as Neo-Hittite or more accurately "Syro-Hittite," was characterized by its raw, yet highly original elements, despite clear influences from Hittite and Assyrian traditions. It is argued that this art style should not be attributed to any single ethnic group, such as the Hittites, Hurrians, or Arameans, but rather to a broader North Syrian cultural environment.

Although the Arameans are thought to have had limited artistic traditions of their own due to their Bedouin origins, it is likely they still contributed to the artistic landscape of the region. Future studies focusing on detailed stylistic analysis, particularly of the bas-reliefs found in Tell Halaf, might shed more light on their influence on this North Syrian artistic movement.

Last update: October 9, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: