Arianism and the Defense of Orthodoxy: The Battle Over the Nature of the Son of God

Arianism, named after its founder Arius, a Christian priest from Alexandria, was a theological doctrine that challenged one of the most central beliefs in early Christianity—the nature of the Son of God and his relationship to God the Father. Arius taught that the Son of God, although divine, was not equal to God the Father. He believed that the Son was a creation of the Father, implying that the Son of God was not eternal but had a beginning in time. Arius expressed this view succinctly with the phrase: “There was a time when he [the Son] was not.”

This belief directly contradicted the orthodox Christian teaching that both the Father and the Son are eternal and co-equal. Arius’s ideas sparked a significant theological controversy that eventually led to one of the most critical events in Christian history—the First Council of Nicaea.

Arius - detail of Byzantine icon depicting the First Council of Nicaea.

The Clash with Orthodox Christianity

The teachings of Arius quickly attracted opposition, especially from Alexander, the bishop of Alexandria, who vehemently disagreed with Arius's claim that the Son of God was a creation rather than eternal. This theological dispute grew to the point where Arius sought support from other influential figures, notably Eusebius, the bishop of Nicomedia, who had strong political connections, including the ear of Emperor Constantine the Great.

In an effort to quell the growing discord that threatened the unity of the Christian Church, Constantine called for a general council, the First Council of Nicaea, in 325 CE. At this council, 318 bishops gathered to debate the teachings of Arius. The outcome was a definitive rejection of Arianism, and the bishops formulated the Nicene Creed, which clearly stated that the Son of God was "God from God, Light from Light, True God from True God, begotten, not made, consubstantial (of the same substance) with the Father."

The term homoousios (meaning "of the same substance") became the defining concept that encapsulated the orthodox belief in the equality of the Son and the Father, countering Arius's claim of inequality. This doctrine of consubstantiality was established as the cornerstone of Christian orthodoxy, symbolizing the unity and divine nature of the Son in relation to the Father.

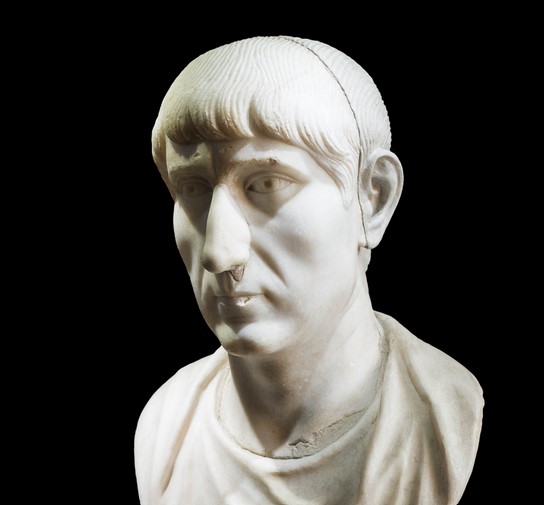

Late Roman bust of a man in Luna marble, Museo Nazionale Romano. Usually dated to the fourth or fifth century, though possibly a modern fake. Sometimes identified as a member of the Constantinian dynasty, especially the emperor Constantius II (317–361), son, co-emperor, and successor of Constantine the Great, but also identified as the emperor Valens (364–378).

Arianism’s Continued Influence and Imperial Support

Despite the council's clear condemnation of Arianism, the doctrine continued to thrive, partly due to the political and religious complexities of the time. Several emperors and high-ranking officials were sympathetic to Arian views, which allowed the doctrine to persist in various forms throughout the empire. Some emperors even attempted to enforce theological compromises to maintain political peace and unity, which only deepened the divisions within the Church.

One reason for Arianism's resilience was the theological disagreements over the use of the term homoousios. Some orthodox bishops rejected the term because they believed it lacked a basis in scripture, while others feared it was too closely associated with Sabellianism, another heretical doctrine that blurred the distinction between the Father and the Son by presenting them as mere modes of a single divine entity.

Athanasius and the Defense of Nicene Orthodoxy

The staunchest defender of the Nicene Creed and its doctrine of the Son’s equality with the Father was Athanasius of Alexandria, who succeeded Alexander as bishop. Athanasius argued passionately that the Son of God must be divine in the fullest sense to fulfill his role as the redeemer of humanity. According to Athanasius, only someone who was truly God could bring humanity back into communion with God through his sacrifice.

Athanasius's unwavering stance against all forms of Arianism led to repeated conflicts with both political and religious authorities. He was exiled from his position five times, demonstrating the volatile nature of the theological and political landscape of the period. Despite these setbacks, Athanasius continued his mission, organizing synods like the one held in Alexandria in 362 CE, which helped clarify misunderstandings and consolidate the orthodox position.

The Role of the Cappadocians and the Second Council of Constantinople

After Athanasius's death, his cause was championed by the Cappadocian Fathers—Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus. These theologians played a crucial role in refining and expanding upon the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity. Their theological contributions laid the groundwork for the Second Ecumenical Council, the Council of Constantinople in 381 CE, which reaffirmed the Nicene Creed and definitively condemned Arianism once more.

This council expanded the Nicene Creed to include more explicit statements about the Holy Spirit, further solidifying the orthodox understanding of the Trinity as three distinct but co-equal and co-eternal persons within one divine essence.

The Legacy of Arianism and its Decline

Although the influence of Arianism gradually waned after the Council of Constantinople, it did not disappear entirely. Variants of Arian beliefs continued to exist in some Christian communities, especially among the Germanic tribes, well into the medieval period. However, by the end of the 5th century, Nicene orthodoxy had firmly established itself as the dominant doctrine in both the Eastern and Western branches of the Christian Church.

Last update: October 16, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE