Ashurbanipal the great

King of Assyria, King of Sumer and Akkad, King of the Lands, King of the Four Corners of the World and King of the Universe

Ashur-ben-Apal, known in modern times as Ashurbanipal, was the son of Ashur-ahu-iddin (Esarhaddon). He was the most powerful king of Assyria (669–631 BCE), and, according to legend, he built the cities of Anchiale and Tarsus in a single day.

He became proverbial for his indulgent and lascivious lifestyle. It is said that when he was on the brink of losing his kingdom, he withdrew to live in seclusion with all his riches in a grand palace in Nineveh. There, far from his subjects but surrounded by wives, concubines, and bodyguards, he abandoned himself to unrestrained pleasures until he grew weary of life and allowed himself to die.

Over time, his memory faded until two centuries after his death, when an inscription attributed to him ("L," lines 13–18) was brought to light in Nineveh:

I have learned what the sage Adapa brought [to men], the hidden meaning of all written knowledge. I am initiated into [the science of] omens of heaven and earth. I am able to participate in discussions among scholars, to debate the hepatoscopic series with the most expert diviners. I know how to solve 'reciprocals' and 'products' that have no given solution. I am skilled at interpreting scholarly texts, whose Sumerian is obscure and whose Akkadian is difficult to uncover. I penetrate the meaning of stone inscriptions from before the Flood, which are hermetic, enigmatic, and tangled.

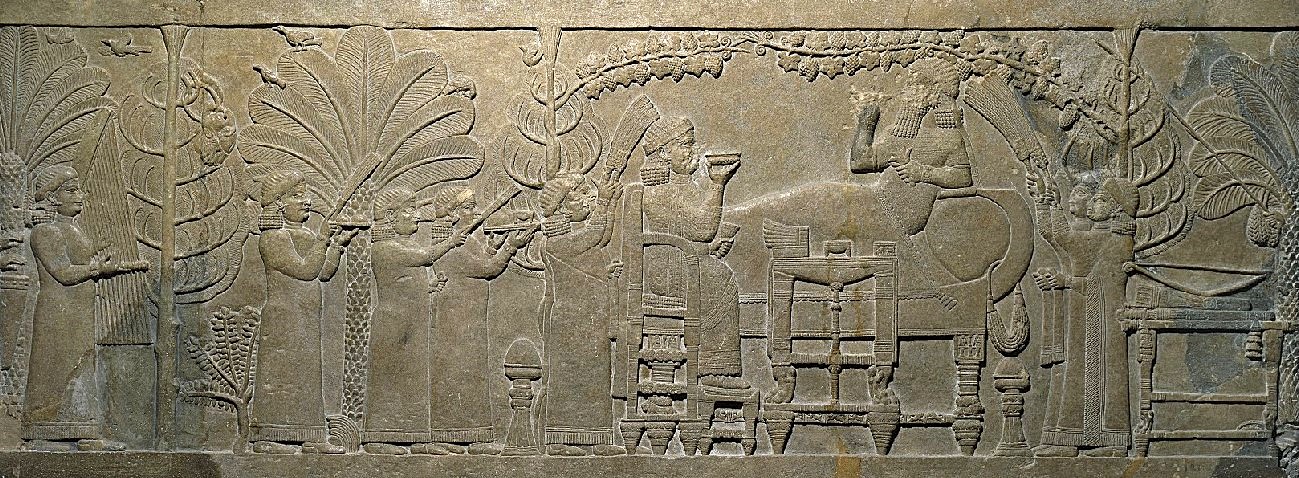

Assyrian Relief of the Banquet of Ashurbanipal From Nineveh Gypsum N Palace (645-640 BCE)- British Museum.

The "Garden Party" relief, depicting Ashurbanipal (right) and his queen Libbali-sharrat (left) . Gypsum wall panel relief fragment; carved in low relief; the topmost register is represented by the 'Garden Scene' with birds and a locust in the trees, showing (from left to right) two women holding napkins and fanning the queen with fly-whisks; two more each bring a dish, which they protect with a fly-whisk, towards the enthroned queen and reclining king, who feast in the arbour amid the vines, conifers and palms, hung with the grisly trophies of victory, consisting of the head and hand holding a wand of Teumman, king of Elam. The hands of a woman drummer and a woman harpist can be seen amid the palms and conifers. Behind the king stand two more ladies holding napkins and fanning him, and behind them is a table holding his sword, bow and quiver. The furniture is very elaborate.

From that point on, he became known to the Greeks, who, fascinated by the deeds of this king from a distant time and civilization, created their own tales. The first to recount his legends was Herodotus in the 5th century BCE, who Hellenized his name to Sardanapalus. In the following century, Ctesias of Cnidus wrote the first complete biography of Ashur-ben-Apal, filled with anecdotes and curiosities.

Diodorus Siculus, drawing on Ctesias’s account in his Persika, narrates that Sardanapalus was the last of a line of 30 Assyrian kings and the most depraved among them. He loved dressing as a woman, engaging in traditionally feminine tasks, exhibited an excessive love for food, indulged in unspeakable carnal passions, and encouraged his subjects to pursue similar pleasures. Ashur-ben-Apal suffered several defeats after previously triumphing over many rebels. Besieged in his capital, he supposedly allowed himself, his family, and his treasures to be consumed by flames. The Mede Arbaces would succeed him on the throne.

The name Sardanapalus became synonymous with “a person who lives in luxury, pleasure, and dissipation.” However, this perception of the king stems from a misinterpretation by the Greeks of an inscription Ashurbanipal himself had prepared for his funerary monument, where he instead invited all to eat, drink, and love.

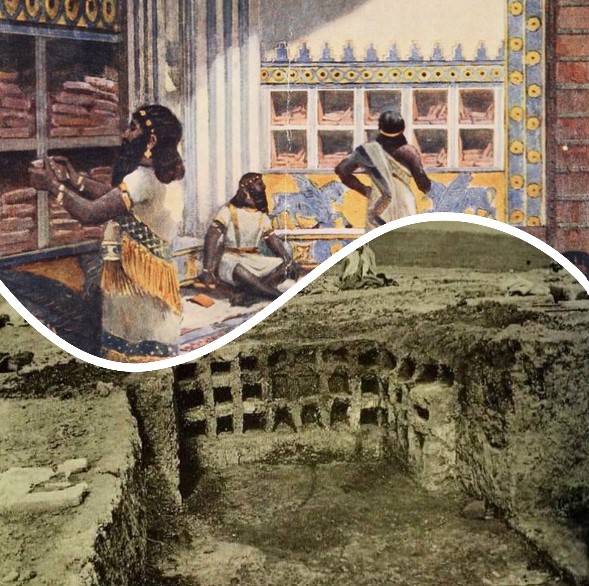

Reconstruction of the Library of Ashurbanipal from Hutchinson's History of the Nations' (1915) and its finding

Ashurbanipal was the last great king of Assyria: under him, the empire reached its zenith before a rapid decline. He was rich, powerful, and cultured, and, unlike other rulers of his time, he could read and write. A patron of art and literature, his reign saw the Assyrian kingdom achieve its greatest cultural flourishing. The monuments and the Royal Library of Nineveh bear testament to this.

Ashurbanipal used the vast resources at his disposal to build the Library, a collection of over 100,000 texts and documents of various genres. This library, for example, preserved the most complete texts of the Epic of Gilgamesh and was surpassed in fame only centuries later by the Library of Alexandria. He also promoted the artistic working of stone, excelling in both sculpture and architecture.

Relief depicting tongue removal and live flaying of Elamite chiefs after the Battle of Ulai (653 BCE).

In addition to these achievements, Ashurbanipal is remembered as one of the most brutal Assyrian kings. In Assyrian royal ideology, the king was the mortal representative of Ashur, chosen by divine will. The king was seen as having a moral, humane, and necessary obligation to expand Assyria, as lands outside of Assyria were considered uncivilized and a threat to the cosmic and divine order within the Assyrian empire. Expansionism was thus framed as a moral duty to transform chaos into civilization rather than as exploitative imperialism.

Because the Assyrian king represented Ashur, resistance or rebellion against Assyrian rule was viewed as opposition to divine will, warranting punishment. Assyrian royal ideology perceived rebels as criminals against the divine order of the world. While this ideology often justified brutal punishments against Assyria's enemies, the levels of brutality and aggression varied considerably among kings. Modern scholars do not consider ancient Assyria as a whole to have been an unusually brutal civilization.

For instance, Sargon II, the founder of Ashurbanipal’s dynasty, was known for pardoning and sparing defeated enemies on multiple occasions, and most kings directed their brutality against enemy soldiers or elites, not civilians. In contrast, Ashurbanipal boasted of bloody massacres of rebellious civilians, as exemplified in the extensive destruction of Elam, which some scholars describe as an ancient genocide.

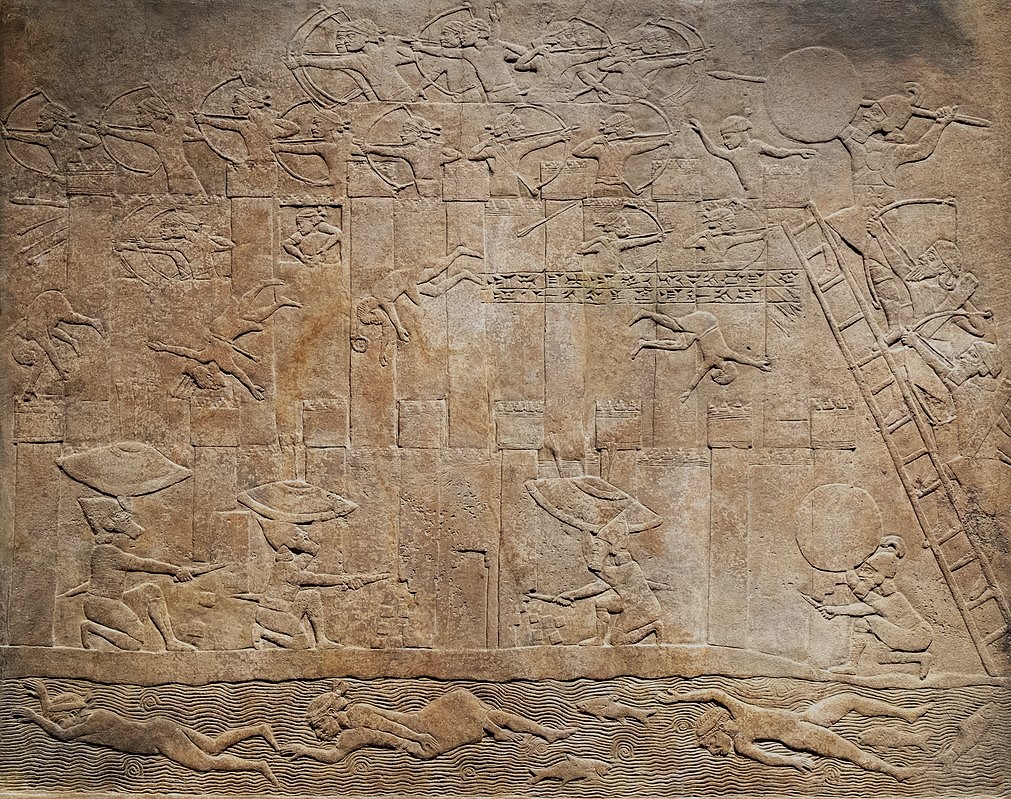

Relief depicting the Assyrians besieging the Elamite city of Hamanu in 646 BCE.

During his reign, early but irreversible signs of the Assyrian Empire's decline began to emerge. These included the loss of Egypt, the inability to resolve the enduring problems posed by Babylon and the Chaldean tribes, and the failure to prevent the rise of the Median kingdom. Many of Ashurbanipal's battles yielded little strategic advantage while draining time and resources. They weakened the empire’s strength and fueled anti-Assyrian sentiment in southern Mesopotamia, possibly contributing to the rise of the Neo-Babylonian Empire five years after his death.

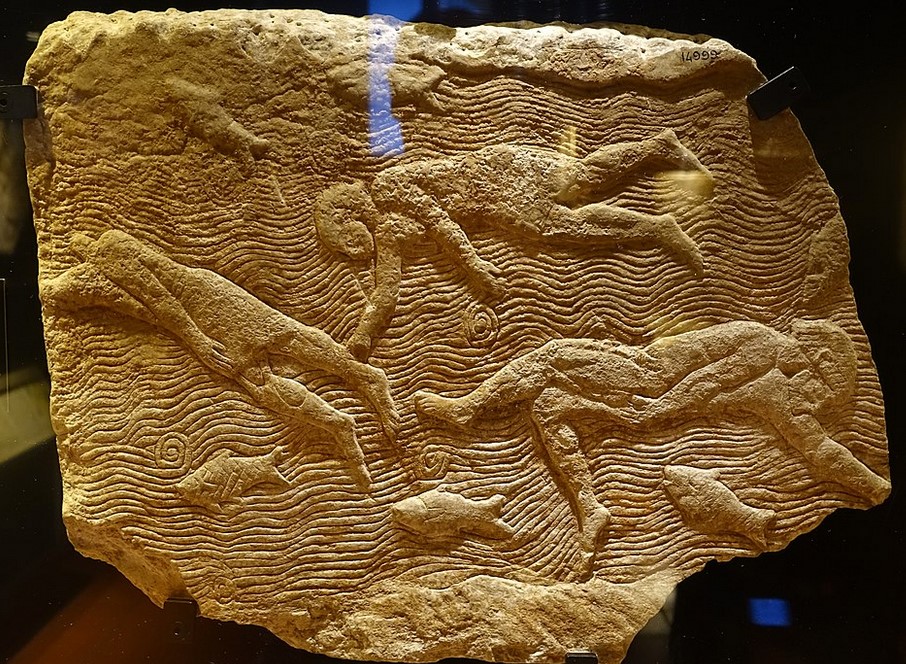

Relief from Ashurbanipal's palace depicting corpses floating down a river - The Egyptian Museum in Vatican Museums.

Last update: December 7, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: