The Evolution of Ancient Athenian Government: From Monarchy to Democracy

Ancient Athens went through a significant transformation in its governance, transitioning from a monarchy to a democracy, which set the stage for the city-state's cultural and political dominance in the ancient world. This transformation, which took place over centuries, involved multiple political reforms, power struggles, and social changes, ultimately leading to the establishment of one of the earliest forms of democracy in history.

The Acropolis of Athens

The Monarchical Era

During the Archaic Period, which lasted from approximately 8000 to 1000 BCE, Athens was initially ruled by a king known as the basileus. The king wielded considerable power, overseeing the city-state's governance and military affairs. Athens’ advantageous geographic position, located near a harbor with fertile agricultural lands, helped it thrive economically and resist invasions. As trade expanded, so did the wealth and influence of the city, leading to a gradual decline in the power of the king.

As the wealth of Athens grew, it fostered the rise of a group of nobles who formed a council known as the Areopagus. The Areopagus derived its name from the hill upon which they met and slowly began to usurp the king’s authority. The members of this council were predominantly aristocrats who had accumulated wealth through their control over the lucrative olive oil and wine markets. With their economic power came political influence, which they used to limit the monarch’s control over Athens.

Transition to Oligarchy

Over time, Athens transitioned into a de facto oligarchy. The Areopagus assumed the central role in governance, and they appointed nine archons to manage the day-to-day affairs of the state. While the archons were responsible for decision-making, they were still answerable to the Areopagus, ensuring that the council retained the ultimate authority over political matters. After serving their term, these archons would join the Areopagus, further cementing the council's power.

This oligarchic rule led to a concentration of power among the wealthy elites, who were mainly involved in the production of olive oil and wine. As a result, common Athenian citizens, particularly wheat farmers, were marginalized. When Athens started trading for cheaper wheat from other regions, local farmers found themselves in economic distress, often resulting in debt and even partial slavery. This situation highlighted the inefficiencies of the oligarchic system, particularly its failure to address the needs of the broader population

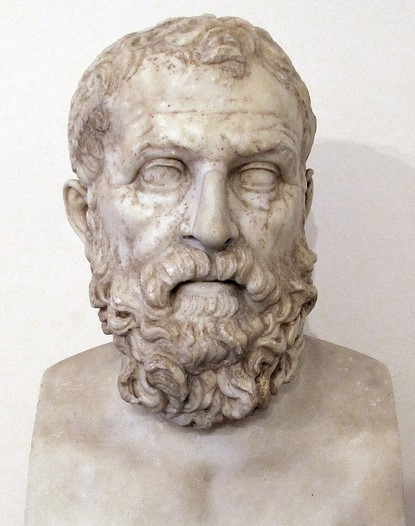

Ancient bust of Solon. Roman copy (c. 90 CE) of a Greek original (c. 110 BCE) from the Farnese Collection. Today, it is kept at the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Solon's Reforms

Recognizing the need for change, the Athenian elites decided to appoint a reformer who could restructure the government and address the economic inequalities. Solon, a respected lawmaker, poet, and former archon, was chosen for this task. Solon implemented a series of radical reforms aimed at easing the economic burdens of the common people. He annulled existing debts, freed many citizens from enslavement, and prohibited the practice of using human beings as collateral for loans. Additionally, Solon encouraged small farmers to engage in the cultivation of wine and olive crops to diversify their economic opportunities.

Solon also introduced a new constitution that restructured the political hierarchy into four classes based on wealth. This arrangement allowed the wealthiest two classes to continue serving on the Areopagus, while the third class gained the ability to participate in a newly formed council of 400 citizens. This council served as a counterbalance to the power of the Areopagus. The lowest class was permitted to take part in the assembly, giving them a voice in electing some local leaders. Solon’s reforms laid the groundwork for a more inclusive political structure by instituting trial by jury and reorganizing the judicial system. However, after completing his reforms, Solon stepped down, returning control to the Areopagus.

Cleisthenes and Peisistratus

The Rule of Peisistratos and the Rise of Cleisthenes

Despite Solon's reforms, the economic situation in Athens did not improve significantly, leading to the rise of Peisistratos, a military general who seized power. Peisistratos, while supporting Solon's constitutional framework, implemented his own reforms in both the economy and cultural practices, strengthening Athens internally. Upon his death, his son, Hippias, proved less capable of holding power, leading to Athens being briefly controlled by Sparta and its allies.

This period of instability set the stage for Cleisthenes, a noble who eventually took control after Isagoras, the Spartan-supported ruler, was overthrown. Cleisthenes initiated sweeping reforms that laid the foundation for Athenian democracy. He extended political rights to all free men in Athens, allowing them to participate in the decision-making process. Cleisthenes reorganized the government, creating a council composed of elected male citizens over the age of 30, who were responsible for guiding the city-state’s governance.

To prevent any individual from amassing too much power, Cleisthenes introduced the practice of ostracism, where citizens could vote to exile a potentially dangerous figure from Athens for a period of at least 10 years. This reform ensured that the democracy remained stable and safeguarded against the rise of tyrants.

The Decline of the Areopagus

The Areopagus, which once held supreme power in Athens, gradually lost its influence as democracy took root. Initially, the council had served as the guardian of laws, public morality, and religious practices, composed predominantly of aristocrats with conservative leanings. However, as democratic reforms progressed, starting with Cleisthenes and furthered by leaders like Ephialtes and Pericles in the 5th century BCE, the powers of the Areopagus were significantly diminished.

These leaders transferred most of the council’s political and judicial authority to newly established democratic institutions. The Areopagus's role was reduced to handling cases related to religious violations and homicide. While the council experienced a brief revival during periods of political instability and the rise of the Hellenistic civilization, it never regained its former dominance.

Last update: October 17, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: