Marcus Aurelius, The Stoic Philosopher-Emperor and His Legacy in Roman History

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, born in 121 CE and known as one of Rome's most revered emperors, left a lasting imprint on both the Roman Empire and the field of philosophy. His life and reign exemplify a blend of military prowess, philosophical reflection, and political acumen. Raised in an era of relative stability, his later rule was marked by continual warfare and the burden of leadership in turbulent times. His legacy is deeply intertwined with Stoic philosophy, which guided not only his personal life but also his approach to governance, leaving a profound influence on Roman culture and history.

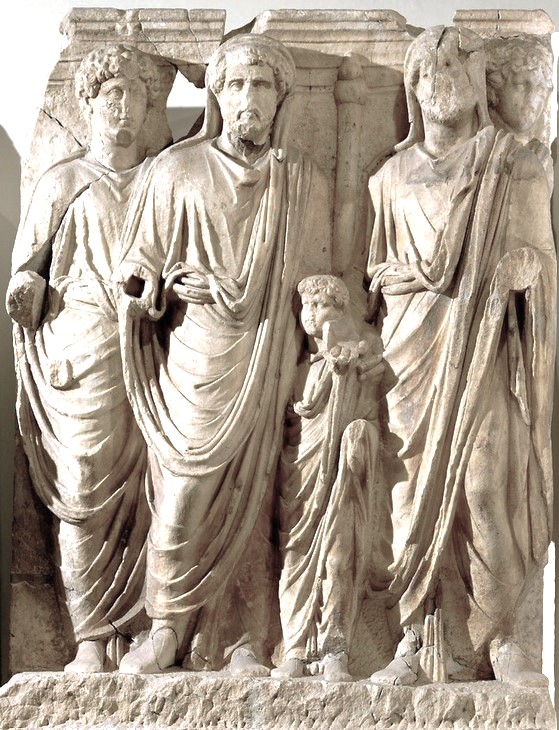

A bust of Marcus Aurelius as a boy, 140 CE. From Albani Collection - Capitoline Museum, Rome

Early Life and Education

Marcus Aurelius was born Marcus Annius Verus in Rome to an affluent and influential family: he was the son of the praetor Marcus Annius Verus and his wife, Domitia Lucilla Minor (also known as Domitia Calvilla).

Domitia Calvilla was the daughter of the Roman patrician P. Calvisius Tullus, but through her mother Domitia Lucilla Maior had inherited a great fortune (described at length in one of Pliny's letters), which included a tile and brick factory near Rome – a profitable enterprise in an era when the city was experiencing a construction boom –, close to the river Tiber. The factory provided bricks to some of Rome's most famous monuments including the Colosseum, Pantheon and the Market of Trajan, and exported bricks to France, Spain, North Africa and all over the Mediterraneany.

A fragment of a brick with stamp of Domitia Lucilla minor (first fourth of IInd century CE) found in Rome - Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome

The Annii Veri were a Roman family settled in the small colony of Ucubi (Colonia Claritas Iulia Ucubi) south-east of Córdoba in Iberian Baetica (modern Andalusia, Spain); they were of Italic origins, and had legendary claims of descendance from Numa Pompilius. This family rose to prominence in Rome in the late 1st century CE. Marcus's great-grandfather Marcus Annius Verus was a senator, while his grandmother Rupilia Faustina was the step-daughter of Salonia Matidia, who was the niece of the emperor Trajan. So, Marcus was related to the Nerva-Antonine dynasty.

Marcus was three when his father died, and was raised by his mother and paternal grandfather (the Roman senator Marcus Annius Verus, brother of Faustina the Elder, wife of Antoninus Pius, who married to Domitia Lucilla, the heiress of a wealthy family which owned a tile factory.) In his Meditations, Marcus Aurelius says of his father: "From what I heard of my father and my memory of him, modesty and manliness.".

His upbringing was shaped by his adoptive grandfather, who ensured he received a well-rounded education in various fields such as philosophy, rhetoric, law, and even painting. His philosophical leanings were particularly shaped by the Stoic doctrines, a path he pursued with a deep sense of dedication and discipline despite his fragile health. The teachings of Epictetus and the broader tenets of Stoicism resonated with Marcus, shaping his character into one of self-control, and a profound commitment to ethical conduct.

Scene of adoption from Ephesus (Monument of the Parthians, now at the Museum of Ephesus in Vienna): Antoninus Pius (centre) with the seven-year-old Lucius Verus (right) and the seventeen-year-old Marcus Aurelius (left) at the time of their adoption. Next to him could be Publius Elianus Trajan Hadrian (extreme right).

After Hadrian's adoptive son, Aelius Caesar, died in 138, Hadrian adopted Marcus's uncle Antoninus Pius as his new heir. The intellectual foundation of Marcus Aurelius distinguished him early in life, attracting the attention of Emperor Hadrian, who saw potential in him. Hadrian died that year, and Antoninus became emperor. Hadrian arranged for Marcus to be adopted by his successor, Antoninus Pius, along with Lucius Verus (the son of Aelius), setting the stage for his future role as emperor. This strategic adoption in 138 CE changed his destiny and name, marking the beginning of his formal preparation for leadership.

Upon his adoption by Antoninus as heir to the throne, he was known as Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus Caesar and, upon his ascension, he was Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus until his death.

Roman Empress Faustina the Younger. This motherly portrayal with wavy hairstyle and the large bun was made in 161 CE on the occasion of the twin birth of boys. The grand bust made of alabaster dates from the early 18th century CE. Marble. Acquired in Paris, France, in 1742 CE. Altes Museum in Berlin.

He married his cousin, Annia Galeria Faustina (130 - c.176 CE), known as Faustina the Younger to differentiate her from the eldest daughter of Emperor Antoninus Pius and Empress Faustina the Elder. Initially, Emperor Hadrian intended for Faustina to marry Lucius Verus, but she was eventually betrothed to Marcus Aurelius in 139 CE, with their marriage taking place in April or May of 145 CE. Since Marcus Aurelius was legally the adopted son of Antoninus Pius, Roman law technically considered Faustina his sister. For the marriage to proceed, Antoninus Pius would have needed to formally release one of them from his paternal authority (patria potestas).

Although little is documented about the ceremony itself, it was described as "noteworthy." Coins were minted featuring the portraits of the couple, and Antoninus Pius, serving as Pontifex Maximus, likely officiated the ceremony. Marcus Aurelius does not seem to mention the marriage in his existing letters and makes only occasional references to Faustina. After the birth of their first child, Domitia Faustina, on December 1, 147, Faustina was granted the title of Augusta.

Bust of Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla or Lucilla, daughter of Marcus Aurelius, wife of her father's co-ruler and adoptive brother Lucius Verus and an elder sister to later emperor Commodus. Commodus ordered Lucilla's execution after a failed assassination and coup attempt when she was about 33 years old. The bust came from the excavations for the Quirinale tunnel carried out in 1901 - Centrale Montemartini, Rome.

Marcus Aurelius always loved devoutly his wife and from whom he had 13 children (including two sets of twins). Faustina the Younger died in 176 in the East and was buried in the Mausoleum of Hadrian (today known as Castel Sant'Angelo, Castle of the Holy Angel). Lucius Aurelius Verus and her sons died prematurely were also buried in the tomb of the Roman emperor Hadrian (also called Hadrian's mole).

The Hadrian's mole

Ascension to Power and Early Reign

Upon the death of Antoninus Pius in 161 CE, Marcus Aurelius ascended to the throne. In a significant break from tradition, he chose to rule jointly with his adoptive brother Lucius Verus, a decision that demonstrated his preference for shared governance and collaboration. This dual rule was a historic first for Rome, with two emperors jointly holding the title of Augustus.

The initial years of Marcus Aurelius’s reign were filled with military conflicts and political instability. The empire faced numerous external threats, notably from the Parthians in the East and various Germanic tribes along the Danube. Lucius Verus led the campaign against the Parthians, successfully pushing them back and securing key territories. The success was short-lived, however, as the empire was soon engulfed in a series of crises on multiple fronts.

On left, portrait of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, Turkey

The Marcomannic Wars and Challenges to the Empire

The most severe threat to Marcus Aurelius's reign came from the Germanic tribes, particularly the Marcomanni and the Quadi, who invaded Roman territories along the Danube. This conflict, known as the Marcomannic Wars, spanned much of Marcus's later reign, proving to be a grueling test of his leadership and military strategy. The invaders breached the Alps, reached Northern Italy, and even threatened the important city of Aquileia, indicating the vulnerability of Rome's northern defenses.

Amidst these battles, the empire also faced a devastating outbreak of plague, which further weakened its armies and reduced manpower. This epidemic, likely brought back by troops returning from the Eastern campaigns, ravaged the population, creating additional hardships for Marcus Aurelius as he struggled to sustain the defense and stability of the empire.

To cope with these challenges, Marcus Aurelius displayed remarkable resilience and resourcefulness. He mobilized financial resources by auctioning off valuable imperial assets and initiated the formation of new legions to replenish his forces. His strategic military actions eventually led to the defeat of the Quadi, Marcomanni, and other tribes, securing a fragile peace along the empire's borders.

Marcus Aurelius celebrating his triumph over Rome's enemies in 176, riding in a quadriga chariot - Capital Museums, Rome

Internal Policies and Social Reforms

In domestic affairs, Marcus Aurelius’s governance was marked by a deep respect for the Roman Senate and a desire for their counsel in state matters. His administrative style was characterized by a blend of firmness and compassion, as he sought to address the empire's financial difficulties with careful fiscal management and reduced opulence in the imperial court.

One of his notable reforms was in the legal system, where he implemented measures to protect the rights of slaves and to ensure the fair treatment of minors. His legislative efforts aimed to curtail the abuses of power and enhance the overall welfare of the Roman citizenry, reflecting his Stoic principles of justice and equality.

However, Marcus Aurelius's otherwise tolerant stance did not extend to the burgeoning Christian community. The period of his reign witnessed several waves of persecution against Christians, driven largely by societal pressures and the empire’s traditionalist values rather than a personal vendetta from the emperor himself. His philosophical conservatism and commitment to Roman religious traditions played a significant role in this intolerance.

The Antonine Plague broke out in 165 or 166 and devastated the population of the Roman Empire, causing the deaths of five to ten million people. Lucius Verus may have died from the plague in 169. When Marcus himself died in 180 CE, likely in either Vindobona (modern-day Vienna) or the military camp at Sirmium (in Pannonia Inferior), he was succeeded by his son Commodus. Commodus's succession after Marcus has been a subject of debate among both contemporary and modern historians.

The Roman Empire during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. His annexation of lands of the Marcomanni and the Jazyges - perhaps to be provincially called Marcomannia and Sarmatia - was cut short in 175 by the revolt of Avidius Cassius and in 180 by his death. The light pink territory to the east is Roman dependencies - the Kingdoms of Armenia, Colchis, Iberia, and Albania.

Philosophical Influence and Writings

Marcus Aurelius's philosophical contributions, particularly his work known as "Meditations" or "Colloquies with Himself," remain one of the most profound testaments to his Stoic beliefs. Written during his military campaigns, these reflections offer a window into his mind, revealing his struggle to maintain virtue and rationality amidst the pressures of war and leadership. The text is divided into 12 books, each filled with thoughts on ethics, duty, and the nature of the universe, deeply influenced by the teachings of Epictetus and Heraclitus.

Central to his Stoic philosophy was the concept of adiaforia, or indifference to external events, focusing instead on maintaining inner peace and moral integrity. Unlike earlier Stoics who might have approached this ideal with unwavering certainty, Marcus's reflections often reveal a tone of melancholy and skepticism. His writings frequently explore themes of mortality, the impermanence of life, and the inevitable decay of all things, which reflects a subtle departure from traditional Stoic optimism toward a more personal and introspective view of existence.

His contemplation on death, a recurring theme in his writings, demonstrates a philosophical resignation to life's transitory nature. Marcus Aurelius grappled with the notion of the soul’s immortality, leaning more towards the idea of death as a release from pain rather than a transition to an afterlife. This perspective aligns closely with both Stoic and Epicurean ideals, emphasizing the acceptance of death as a natural part of life’s cycle.

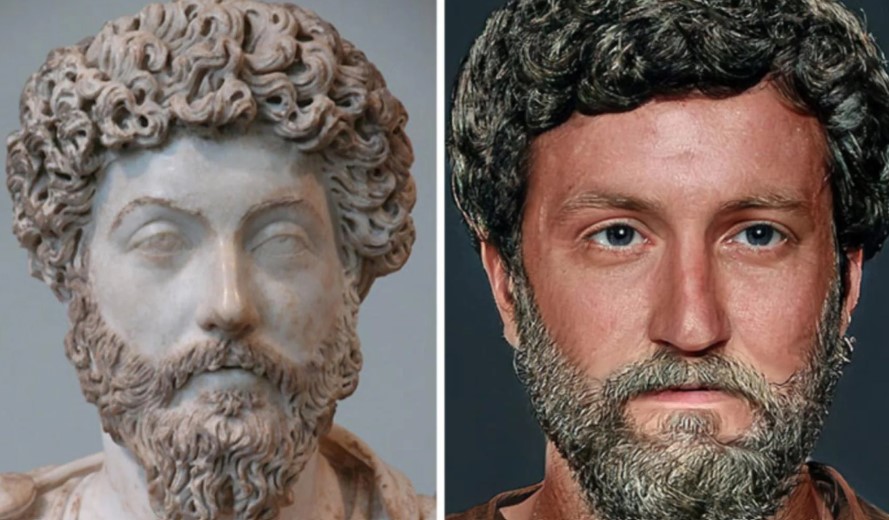

Iconography and Cultural Legacy

Marcus Aurelius's image and legacy have been preserved through a wealth of statues, busts, and monumental reliefs that highlight both his philosophical demeanor and his military achievements. Among the most iconic representations of the emperor is the equestrian statue in bronze that once stood in Rome's Piazza del Campidoglio, symbolizing his enduring influence and authority.

Ancient literary sources do not mention the equestrian statue dedicated to Emperor Marcus Aurelius, but it was most likely erected in either 176 CE, to celebrate his triumph over the Germanic tribes, or in 180 CE, shortly after his death. During that period, Rome was home to numerous equestrian statues; records from the late Imperial era cite 22 such statues, known as equi magni, or larger-than-life-size figures. The statue of Marcus Aurelius, however, stands out as the only one to have survived to this day. Its preservation has given it immense symbolic significance, representing the continuity of Imperial Rome to those aspiring to be its heirs. The statue's first documented location at the Lateran dates back to the tenth century, though it is believed to have been placed there as early as the late eighth century. This timing coincides with Charlemagne's efforts to replicate the layout of the Campus Lateranensis when he moved a similar equestrian statue from Ravenna to his palace in Aachen. In 1538, Pope Paul III directed the Farnese family to transfer the statue to the Capitoline Hill, which had served as the administrative center of Rome since 1143. Following its relocation, the Roman Senate commissioned Michelangelo in 1539 to refurbish the statue. Michelangelo's work went beyond merely providing a suitable setting; he made the statue a central feature of the grand architectural ensemble that became known as the Piazza del Campidoglio.

The architectural tributes to his victories include the Column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, adorned with intricate reliefs depicting his military campaigns against the Germanic tribes. This column, similar in style to Trajan’s Column, narrates the struggles and triumphs of his reign, blending artistic skill with a clear representation of imperial power.

His influence extended far beyond his lifetime, resonating through the centuries and into the late Roman Empire. Even during the era of Constantine, Marcus Aurelius's memory was revered, with his image often symbolizing a moral and philosophical ideal. His impact on later Stoic thought and Roman art contributed to a legacy that positioned him as a philosopher-king, a model of ethical leadership in the face of adversity.

The Column of Marcus Aurelius is a monument in Rome, erected between 176 and 192 to celebrate, perhaps after his death, the victories of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (161-180) obtained on Germans and Sarmatians located north of the middle course of the Danube during the Marcomannic Wars. The column, which was 29.617 meters high (equal to 100 Roman feet; 42 meters if you also consider the base), is still in its original location in front of Palazzo Chigi and gives its name to the square in which it stands, Piazza Colonna. The monument, covered with bas-reliefs, is inspired by the Trajan's Column. The sculptural frieze that spirally rolls around the stem, if it were unwinded, would exceed 110 meters in length.

Last update: October 20, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: