The Rise and Fall of Early Babylon

Babylon, also known as Babel (in Babylonian, Bab-ilu or Bab-ilani), was one of the most influential cities in ancient Mesopotamia and a key hub of early civilization in Asia. Located on the Arakhtu channel of the Euphrates River, near modern-day Baghdad in Iraq, it began as a small settlement that would grow into one of the most powerful and legendary cities of the ancient world. Its rise to prominence is attributed to Sargon of Akkad (circa 2350-2294 BCE), who expanded a pre-existing village into a significant city, marking the start of Babylon's transformation into a political and cultural center.

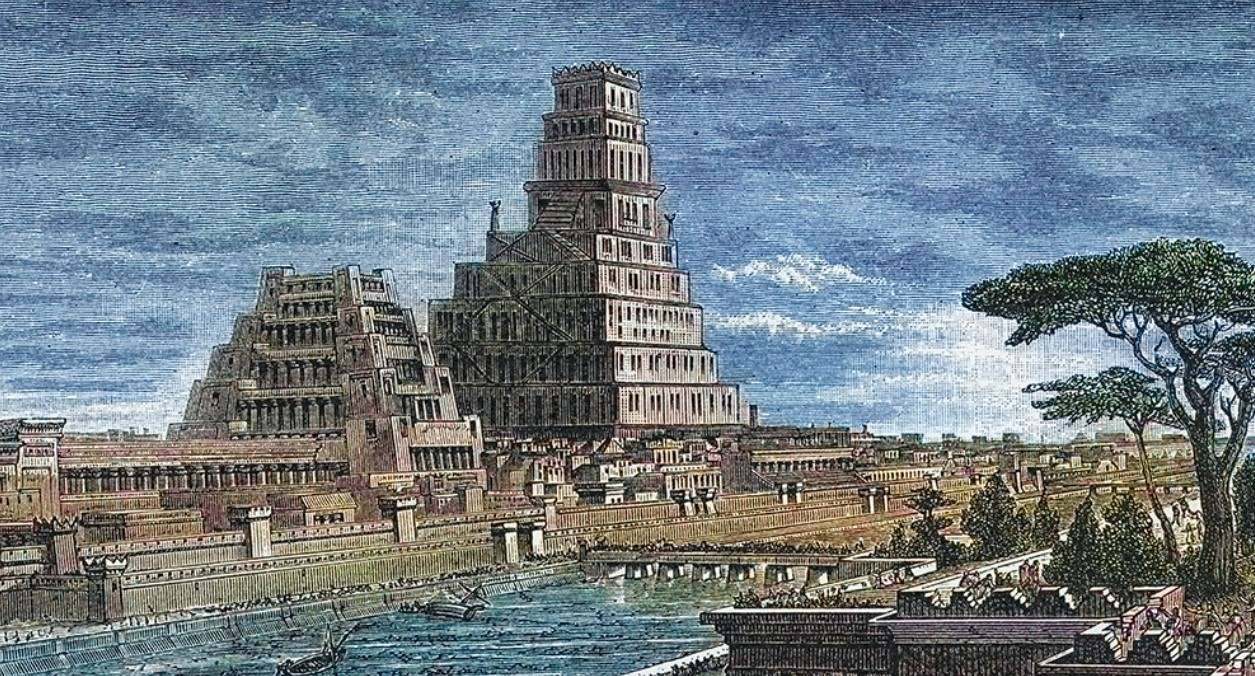

Old engraved illustration of conquest of Babylon

Expansion Under Early Kings: Sargon, Hammurabi, and Samsuiluna

Sargon's efforts to develop Babylon laid the groundwork for future rulers. Following his initial expansions, Babylon saw significant growth during the reign of Hammurabi (1728-1686 BCE), one of the most famous kings in Mesopotamian history. Hammurabi not only strengthened Babylon's defenses and infrastructure but also expanded its reach by founding the twin city of Borsippa. His successor, Samsuiluna (1685-1649 BCE), continued these developments, ensuring that Babylon remained at the heart of Mesopotamian politics and culture.

Early Mentions and Growth: The Emergence of Babylon in the Historical Record

The earliest written records of Babylon date back to the reign of Shar-kali-sharri (2217–2193 BCE), a king of the Akkadian Empire, who is known to have built temples in the city. During the Ur III period (2112–2004 BCE), Babylon gained more significance, with various officials holding the title "governor of Babylon." It was around this time that Mesopotamia experienced an influx of West Semitic nomads, called the Amorites, who began to settle in the region. This migration and settlement played a crucial role in the city's evolution, as the Amorites became key figures in Babylon's political landscape.

The Amorite Dynasty and Expansion of Babylon

In 1894 BCE, Sumu-abum, an Amorite chieftain, founded a new dynasty in Babylon, establishing it as a political entity in its own right. His successor, Sumu-la-el, expanded Babylon's influence by conquering nearby city-states like Sippar, Kish, and Dilbat, asserting Babylon's dominance in the region. However, Babylon was not the only city expanding its territory during this period; other rulers, such as Shamshi-Adad I in Upper Mesopotamia and Rim-Sin of Larsa in the south, were also consolidating their power, leading to a complex network of rivalries and alliances among Mesopotamian city-states.

The Old Babylonian Period and Hammurabi's Rise to Power

The Old Babylonian period, beginning in 1792 BCE with Hammurabi's ascent to the throne, marked a new era for Babylon. Hammurabi's reign is best known for his comprehensive Law Code, one of the earliest and most complete legal codes in history, which influenced legal systems for centuries. Initially, Hammurabi focused on strengthening Babylon’s internal stability by developing its infrastructure, fortifying its defenses, and enhancing its economy. Diplomatically, he maintained alliances with neighboring rulers, including Rim-Sin of Larsa and Zimri-Lim of Mari, to secure Babylon’s position in the region.

Expansion and Unification of Mesopotamia

From 1764 BCE onward, Hammurabi adopted a more aggressive expansionist policy. He successfully defeated a coalition of Elamite, Assyrian, and Eshnunna forces, turning the tide of power in favor of Babylon. The next year, he turned against his former ally, Rim-Sin, and annexed Larsa, bringing most of southern Mesopotamia under Babylonian control. For the first time since the third millennium BCE, both Sumer and Akkad were united under a single kingdom. To symbolize his new status as the ruler of a vast territory, Hammurabi adopted the title "King of the Four Quarters of the World," linking his legacy to the great Akkadian emperor Naram-Sin.

The Conquest of Upper Mesopotamia

Hammurabi’s ambition didn't stop at southern Mesopotamia; he set his sights on the north as well. In 1761 BCE, he betrayed his ally Zimri-Lim of Mari and seized the city. By the end of his campaigns, cities like Ashur, Nineveh, and Tuttul in the north were also brought under Babylon's control. Babylon had become a formidable empire, wielding influence over most of Mesopotamia and asserting its dominance in both political and cultural realms.

Decline and the Fall of the Old Babylonian Dynasty

Despite Hammurabi's achievements, Babylon's dominance was not long-lived. After his death, his son Samsu-iluna faced significant challenges, including invasions by the Kassites, a group from the Zagros Mountains, and the rise of the Sealand dynasty in the southern territories. These threats weakened Babylon's control, and the kingdom began to fragment. The final blow came in 1595 BCE when Murshili I, king of the Hittites, led a campaign against Babylon, sacking the city and ending the Old Babylonian dynasty.

Last update: October 9, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: