Evolution of Domestic Architecture: A Historical Journey Through Dwelling Types and Social Influences

The dwelling or home of humans varies and takes on different forms based on climatic conditions and the availability of building materials. It also reflects the social organization and culture of the group or society at that time.

Model of a mud brick house at Tell Hassuna, Mesopotamia (Iraq), 6000-5000 BCE. This model is based on a house that was excavated in Jericho, one of the world's first cities. The bricks were made of straw with a binder of fine mud, hardened in the hot sun.

The Mesopotamian dwelling presents a rather elaborate domestic typology: built first in compacted earth and later in sun-dried bricks, the Assyro-Babylonian house is typically single-story, with rectangular rooms arranged around a courtyard. This type of house was also common in ancient Persia, Phoenicia, and Palestine.

Pottery model of a house used in a burial from the First Intermediate Period.

Built with light materials (sun-dried bricks and wood), Egyptian civil architecture is poorly documented.

Plaques in faience representing facades of houses. Probably adorned a wooden box. They are finds from the palaces of Malia and Knossos and under a model house. Paleopalacial period (1900-1700 BCE) - Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete, Greece.

The faience consists of sand, quartz, soda ash and lime, and is covered with paint. The colors used are black, dark blue, green-blue or whitish. It was used for the realization of idols, jewelry and other small objects.

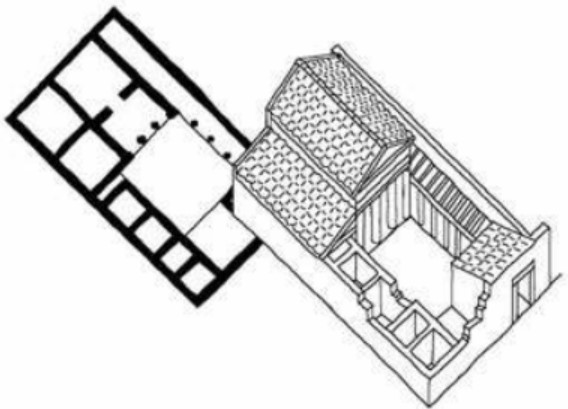

Split of a house in Priene (4th century BCE): around the inner courtyard are the rooms aligned north to south.

In the Greek world, up to the 5th century BCE, houses were very modest, often consisting of just a single room. Later, rooms were arranged around a central courtyard (peristyle), with women’s quarters at the back or on an upper floor. From the 4th century BCE, the peristyle house developed along with urban complexes organized in blocks between straight streets. This model, found in older Mediterranean urban settings, tended to be inward-looking (high enclosing walls with few, very small windows) and open inwardly (large windows or doors onto one or more courtyards).

Remains of a Hellenistic villa in Delos, Greece

Since Mycenaean times (Tiryns, Mycenae, Pylos, Thebes palaces), the home developed around the megaron, a single rectangular room with a hearth, preceded by a vestibule. The Mycenaean palace formed the fundamental structure of the city, contrasting with common dwellings, which typically consisted of a single room built with sun-dried bricks and flat wooden roofs.

In Greece, between the 8th and 4th centuries BCE, common houses maintained a simple structure since public buildings took on great importance in the polis, and little importance was given to private and family life. Nevertheless, the layout of the house acquired a specific character that would be preserved in its later development: the central element, the megaron, center of family and social life, featured simple or double columns, while the vestibule took the form of a portico (the same structure would also become the basis for temple design).

In the classical period, houses included a central courtyard providing access and light to various rooms; sometimes, there was an upper floor where women lived. In the Hellenistic period, homes were larger and had more rooms.

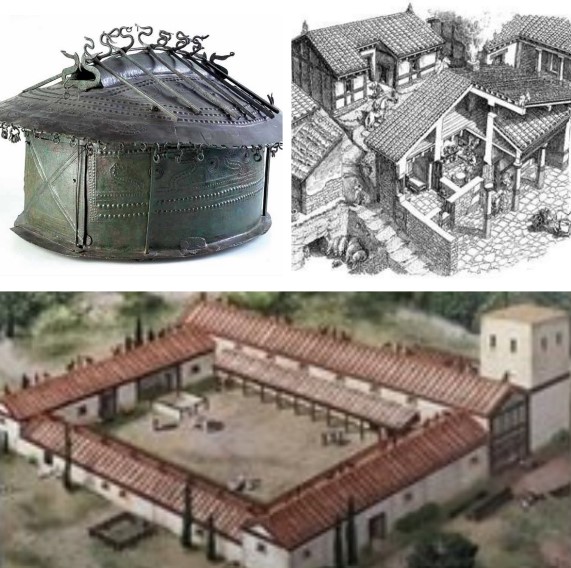

Evolution of the Etruscan dwelling: shaped like a hut (bronze urn from the 8th century BC, Etruscan Museum Etrusco Villa Giulia, Rome), civil and stately home (Murlo Museum, Siena)

Among the Italic peoples and Etruscans, houses were single-story and occupied a limited area. Rooms were arranged around a central courtyard, usually equipped with a basin and cistern; this open area was located closer to the entrance than in the traditional Mediterranean home.

In Etruria, only a few modest examples of houses have survived, but hypogeum chamber tombs often replicate the noble residence, with a typology established between the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, lasting until the 2nd century BCE: an atrium with a tablinum (a formal room, originally also used for sleeping) at the back, flanked by alae (smaller lateral rooms). The earliest Italic houses with an atrium, impluvium, and tablinum were found in Pompeii, where the later evolution of houses is documented.

Hellenistic style buildings: wall painting from the Villa Regina, Boscoreale, near Pompeii, Naples (1st century BCE).

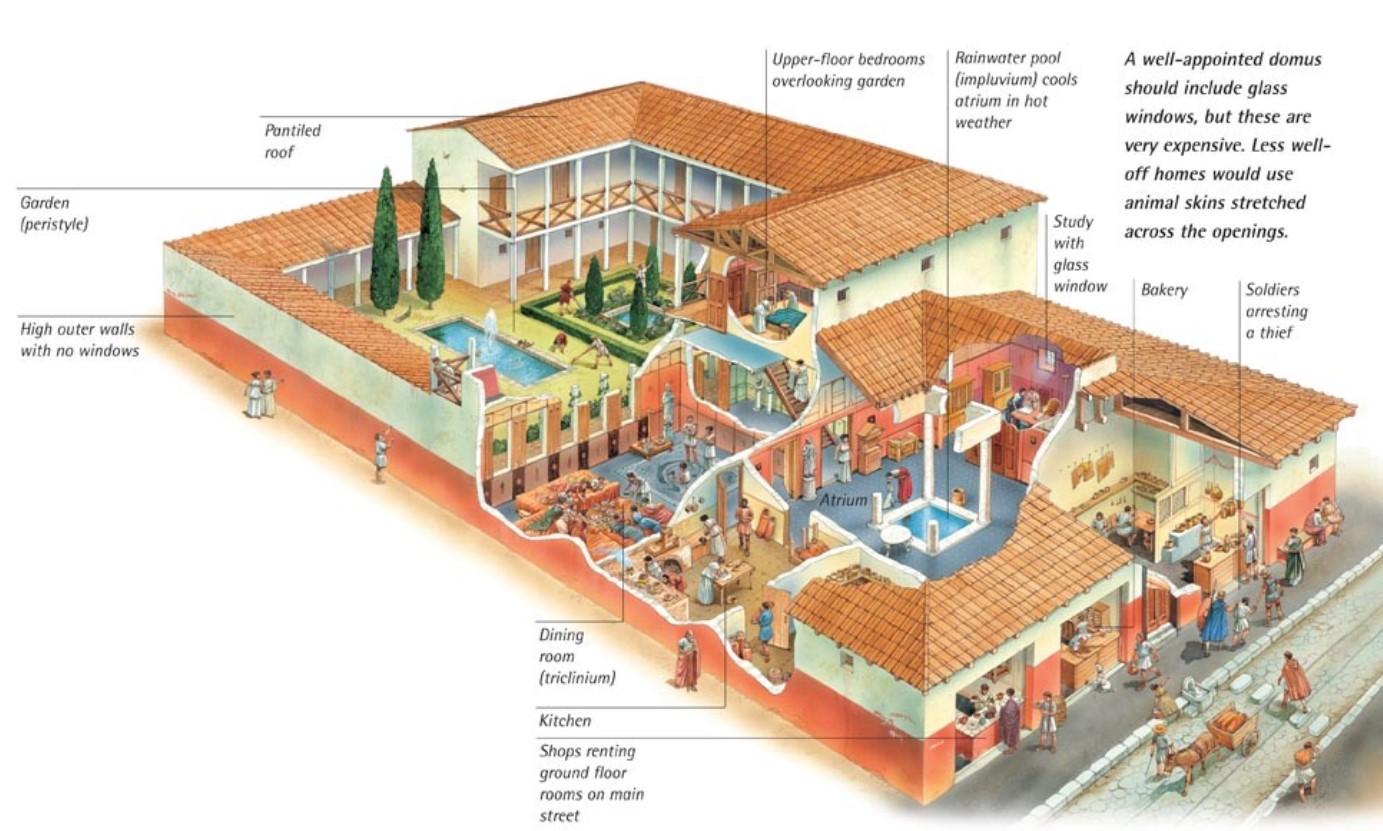

The Roman house was derived from these earlier models. Under the influence of Hellenistic architecture, the typical domus emerged, featuring rooms with canonical proportions and purposes: fauces (entrance corridor), atrium (courtyard), cubicula (bedrooms around the atrium), alae (areas for ancestor worship), triclinium (dining room), tablinum (reception room), and peristylium (courtyard garden).

House with balcony and tabernae in Ercolano, Naples

The lower classes often lived in tabernae, shops or workshops adjacent to or incorporated into noble houses, with living space either in a few rooms behind the shop or on a mezzanine (pergula).

The Silver Wedding House in Pompeii: atrium with an opening in the ceiling (impluvium) and a basin for rainwater (compluvium)

During the Republican period, the home concentrated representative functions in the large, central atrium and the tablinum, used as the main living room; small bedrooms (cubicula) and service rooms (alae) were on the sides, while the rest was occupied by the hortus, a kind of small garden. This type of house, well-documented by Pompeii excavations, often had a second floor with additional bedrooms.

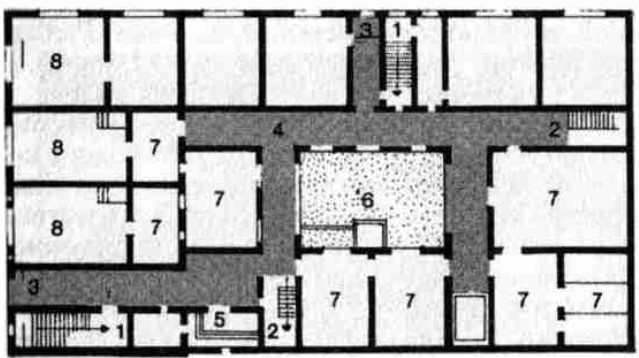

House of Obellio Firmo in Pompeii: Plan of the first floor, ground floor and perspective reconstruction of the exterior: the Tuscan atrium, 2 Corinthian atrium, 3 peristyle, 4 cubicles, 5 tablinium, 6 triclinium, 7 tabernae.

The importance given to private and family life, and the need for spacious, comfortable environments, led to a notable evolution in Roman houses, with differentiation based on social class. The domus, the single-family home of the wealthier classes, became larger and more complex, with a formal entrance (protyrum) opening onto the street and leading to the first open-air courtyard (atrium) or covered courtyard (cavaedium), surrounded by rooms for social activities, guest accommodations, slave quarters, storage rooms (horreum), and the kitchen. From the atrium, through one or two passageways (fauces), one entered the larger inner courtyard (peristylium), center of shared family life for both men and women, around which were bedrooms, dining rooms, party rooms, and shrines to household gods (Lars and Penates). The domus, often comparable in stature to large public buildings, usually developed on the ground floor.

Roman domus

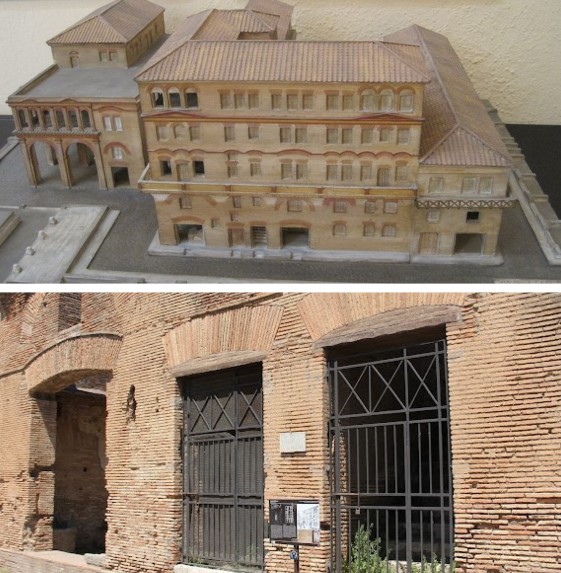

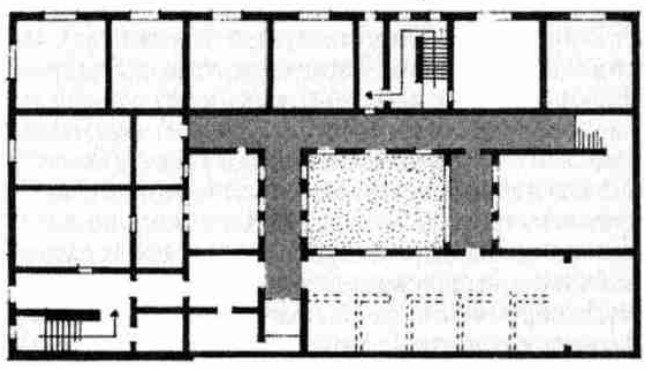

In the Imperial period, however, due to population growth and the cost of urban land, multi-story buildings became common. In Rome and major cities, the traditional single-family house with inward-facing spaces contrasted with multi-family houses growing vertically to meet the increasing population demands. This type of building, the insula, a multi-story structure (some said to reach 10 floors), included rental apartments (cenacula), large rooms from 50 to 200 square meters, subdivided by partitions or simple screens, with windows facing narrow streets; the lower floors usually housed shops (tabernae), and sometimes a complete domus.

Model of Insula (House of Diana, 1st century CE), Ancient Ostia, Rome

Ground floor plan and first floor of the House of Diana: 1) stairs to floors, 2) wooden stairs, 3) entrance corridor, 4) courtyard, 5) latrine (WC), 6) fountain, 7) rooms, 8) tabernae (shops).

In the later Empire, domus were enriched with apsidal halls and loggias.

Through a wide range of typologies, reflecting the growing separation between countryside and urban centers, urban homes began losing the introverted character of Eastern or Greco-Roman traditions, instead featuring extroverted, contiguous single-family homes with two or three floors, steep stairs, and attached shops. Parallel developments included tower-like dwellings, four or five stories high, contributing to the distinctive urban landscape of the post-classical period.

A thermopolium where it was possible to purchase ready-to-eat food, Ancient Ostia, Rome

From the 15th to the 18th centuries, homes largely retained multi-story layouts, with reception rooms on the first floor, bedrooms on the second, and servant quarters in the attic. Buildings designed to emphasize the high social status of the owner featured large courtyards, decorated with arches or colonnades. These became the so-called noble ‘palace.’

'Ideal City' by an anonymous painter (1470-1490), Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino, Italy

Alongside single-family or collective urban homes, suburban noble residences (villas) evolved, featuring diverse functional spaces and specific architectural solutions. Certain types of collective dwellings were also adapted for specific groups, like monasteries and barracks.

Starting in the 19th century, the growing urban population led to an increased number of multi-story apartment buildings, reducing single-family homes.

Technological advancements and varied construction systems allowed the creation of housing types suited to different needs: the modern home adapted the functional divisions of classical times (social life, private life, and services) to the day-and-night area separation that characterizes the middle and upper-middle-class homes of the 20th century. Economic, public, and worker housing reflect the coexistence of various typologies driven by economic and social urban congestion.

Last update: October 30, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE