The Profound Teachings of Jainism

Jainism is one of the oldest and most influential religions to emerge from India, with a history that dates back thousands of years. Despite being lesser-known compared to other major world religions, it has profoundly shaped Indian culture, philosophy, and spirituality. With approximately two million followers primarily in India, Jainism stands as a testament to the power of nonviolence, self-discipline, and spiritual liberation. It is rooted in the teachings of its last great prophet, Mahāvīra, and has since evolved into a diverse and complex tradition with rich philosophical underpinnings.

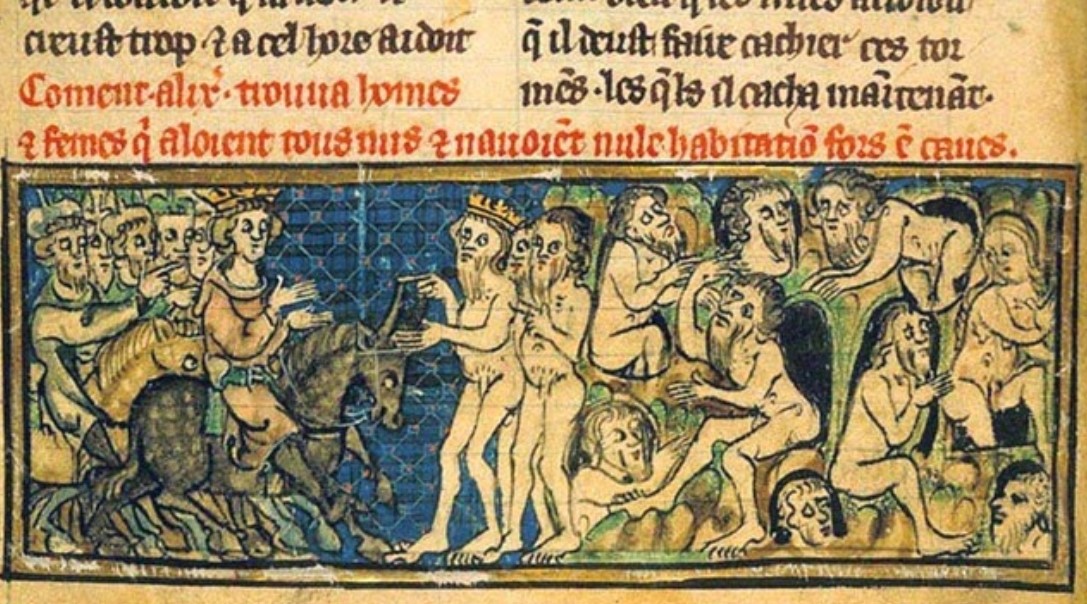

Gimnosophists were the naked and ascetic wise Indians who, answering a riddle-trap, managed to silence the powerful and cultured Alexander the Great and to proselytize even among his officers.

Origins and Foundational Teachings of Jainism

Mahāvīra and the Lineage of Tīrthankaras

Jainism traces its origins to the teachings of Mahāvīra, also known as Vardhamāna, who lived from 599 to 527 BCE. Mahāvīra is considered the 24th and final Tīrthankara, or spiritual teacher, in a long line of enlightened beings who have guided humanity toward liberation. The title "Tīrthankara" translates to "Ford-maker," indicating their role in helping souls cross the ocean of worldly existence toward spiritual liberation. While Mahāvīra is the most well-known, his teachings build upon those of his predecessors, who are believed to have existed over countless ages.

Enlightenment and the Path of Asceticism

Mahāvīra was born into a noble family but renounced his worldly life at the age of 30 to pursue a path of intense asceticism. After 12 years of rigorous practices, during which he faced physical and emotional hardships, he attained Kevala Jnana (absolute knowledge or enlightenment). This state of perfect knowledge is believed to free the soul from the bondage of karma, thus ending the cycle of birth and rebirth. Mahāvīra's enlightenment led him to become a Jina (Conqueror), signifying his victory over desires and material attachments.

Mahāvīra's teachings emphasize that the universe is composed of two fundamental substances: jīva (souls) and ajīva (matter). Souls are inherently pure and possess infinite knowledge, power, and bliss. However, they are trapped in the cycle of samsara (rebirth) due to karma, which binds them to physical existence. The ultimate goal in Jainism is to liberate the soul from this bondage, achieving a state of eternal bliss and omniscience.

The Principles of Jainism: Nonviolence and Ethical Living

The Doctrine of Ahimsa

The principle of Ahimsa (nonviolence) lies at the heart of Jain philosophy and extends beyond physical actions to include thoughts and speech. Jain monks and followers practice nonviolence toward all living beings, from humans to the smallest insects. This commitment to non-harming leads to various practices, such as sweeping the ground before walking to avoid stepping on tiny creatures and wearing masks to prevent inhaling microscopic life forms.

Ahimsa has influenced not only Jain society but also the broader Indian culture, inspiring figures like Mahatma Gandhi, whose philosophy of nonviolent resistance played a crucial role in India's struggle for independence.

Other Key Ethical Principles

In addition to Ahimsa, Jainism prescribes other ethical vows that its followers, especially monks and nuns, must adhere to:

- Satya (truthfulness): Avoiding falsehood in any form.

- Asteya (non-stealing): Refraining from taking anything that is not willingly offered.

- Brahmacharya (chastity): Practicing celibacy or strict sexual discipline.

- Aparigraha (non-possession): Renouncing material possessions to reduce attachment to worldly things.

These strict vows are particularly applicable to the ascetic monks, who lead lives of severe self-discipline. Lay Jains are encouraged to follow these principles to the best of their ability while still participating in society, often engaging in charitable activities and supporting the monastic community.

The Evolution of Jainism: Sects and Schisms

Schism into Shvetambara and Digambara Sects

Following Mahāvīra's death, Jainism eventually split into two major sects: the Shvetambaras (White-clad) and the Digambaras (Sky-clad or naked). This division arose due to disagreements over monastic practices and the interpretation of Jain scriptures.

- Shvetambaras believe that monks can wear simple white robes and that women can attain liberation.

- Digambaras, on the other hand, hold that true renunciation requires monks to remain unclothed to symbolize their detachment from all material possessions, and they traditionally assert that women must be reborn as men to achieve liberation.

Despite these differences in practice and doctrine, the core beliefs of both sects regarding the path to enlightenment and the principles of Jainism remain consistent.

Influence and Spread of Jainism

Jainism experienced significant growth during the reign of the Maurya Empire, especially under the patronage of Chandragupta Maurya (circa 317–293 BCE), who eventually became a Jain monk himself. This era saw Jainism spread across various regions in India, establishing a lasting presence, particularly in the southern and western parts of the country.

The Jain community also produced a vast body of literature, including philosophical texts, devotional hymns, and epic tales known as the Puranas, which narrate the lives of the Tīrthankaras. Jain scholars made significant contributions to fields such as mathematics, astronomy, and logic, influencing both religious and secular thought in medieval India.

Jainism’s Philosophical and Religious Landscape

Atheism and the Concept of Divinity

Unlike many other religions, Jainism does not believe in a creator god or an all-powerful deity governing the universe. Instead, it focuses on the divine potential within each individual soul. Jains revere the Tīrthankaras and other enlightened beings not as gods but as perfected souls who have transcended the cycle of birth and death. These liberated souls serve as role models, guiding others on the path to self-realization and ultimate liberation.

This atheistic yet deeply spiritual perspective distinguishes Jainism from other Indian religions like Hinduism, which centers around a pantheon of gods and goddesses, and Buddhism, which also denies a creator deity but in a different philosophical context.

Liberation and the Ultimate Goal

The ultimate aim in Jainism is to achieve moksha (liberation) from the cycle of samsara. This state is attained through self-purification, the reduction of karma, and the practice of intense meditation and ascetic discipline. When a soul achieves liberation, it is said to reside in a state of eternal bliss, knowledge, and peace in a realm known as Siddhashila, beyond the physical universe.

The rigorous path to liberation can culminate in Sallekhana, a ritual fast to death, which is seen as a final act of self-discipline and non-attachment. This practice is regarded with respect and reverence, symbolizing the soul's final triumph over the body’s needs and the material world.

Last update: October 13, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE