Sabratha, a mix of ancient Mediterranean culture

Ancient Sabratha

Sabratha, an ancient city located in the Tripolitania region of Libya along the Mediterranean coast, is a fascinating site that reveals the layers of history and civilization in North Africa. Originally known in Greek as Abrotonon, this city sits on the Gulf of Gabès, also called the Little Syrtis, approximately 1.5 km northwest of modern-day Sabratha.

The ruins of Sabratha, part of a UNESCO World Heritage site, reflect a blend of Phoenician, Punic, and Roman influences, presenting a unique insight into the ancient Mediterranean world.

Ancient Sabratha

Sabratha's origins trace back to a Phoenician trading outpost established during the first half of the first millennium BCE. This settlement served as a strategic port and trading center, connecting trade routes from the interior of the African continent to the Mediterranean, particularly through Cydamus (modern-day Ghadames). Alongside the neighboring cities of Oea (now Tripoli) and Leptis Magna, Sabratha formed the heart of the maritime region of Emporia within the Carthaginian Empire, known for its prosperity and cultural exchange.

During the Punic Wars, Sabratha came under the rule of Massinissa, king of Numidia, as he expanded his territory between the Second and Third Punic Wars. It is uncertain whether Sabratha, like Leptis, sided with Rome during the Jugurthine War. However, after Julius Caesar annexed the Numidian Kingdom in 46 BCE, Sabratha became part of the Roman province of Africa. The city enjoyed semi-autonomous status as a civitas foederata (a federated city) and later as a municipium, a Roman town with certain privileges, which fostered its growth and prosperity.

Sabratha thrived during the Roman period, especially under Emperor Augustus, as evidenced by coins minted in this period and the construction of the first structures in the forum.

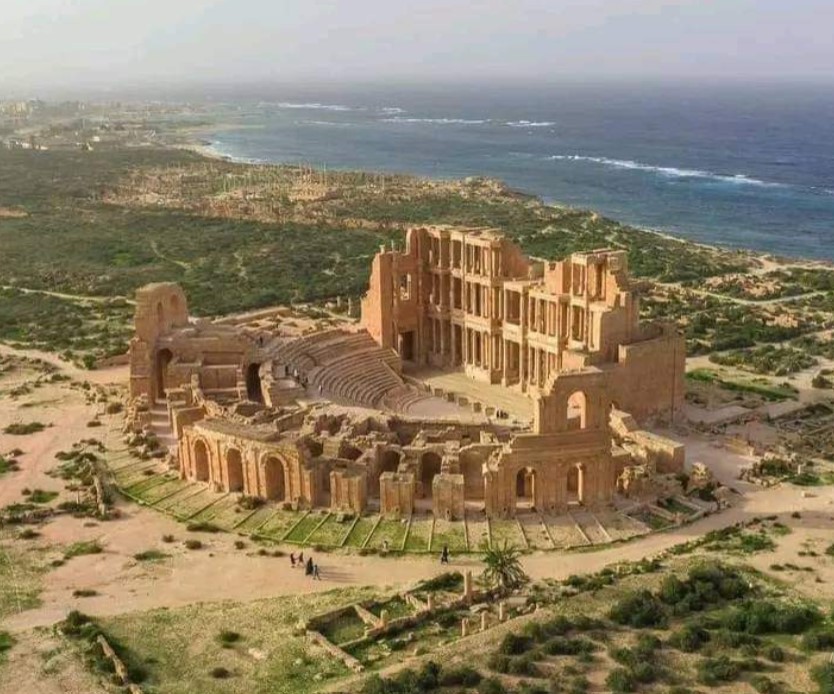

Panoramic image of the theater of the archaeological site, Ancient Sabratha

However, the city's zenith occurred during the second half of the 2nd century CE, with the construction of the magnificent theater, and various religious and civic buildings. During this time, Sabratha was likely granted the status of a Roman colony by Emperor Antoninus Pius, further encouraging its development. Under the Antonine and Severan dynasties, the city reached the height of its prosperity.

This period of growth allowed for a remarkable cultural synthesis, blending Roman influences with Sabratha's enduring Phoenician and Punic traditions. The city also displayed a diverse religious life, incorporating Near Eastern deities such as Egyptian gods like Jupiter Ammon, Serapis, and Isis. The presence of these deities in local sanctuaries speaks to the cosmopolitan nature of Sabratha, where diverse cultures and beliefs flourished under the Roman Empire.

Around 158 CE, Sabratha played host to an event that would be immortalized in classical literature: the trial of the philosopher and author Apuleius. Before the tribunal of the proconsul Claudius Maximus, Apuleius was accused of practicing magic but defended himself with his Apologia. This work not only provides a defense of his actions but also offers a unique glimpse into the daily life and legal practices of the region during the 2nd century. It remains an essential piece of literature for understanding the cultural context of Sabratha at the time.

Sabratha continued to thrive into the 3rd century, maintaining trade connections with Rome, as indicated by the Statio Sabratensium in Ostia, the port of ancient Rome. However, the city faced significant challenges in the mid-4th century CE. Around 360 CE, it was attacked by the Austurians, a tribal group from the interior, marking the beginning of a period of decline. Further incursions from 363 to 366 dealt a severe blow to Sabratha, disrupting trade with the interior regions. Though the local inhabitants, aided by the Roman imperial government, undertook efforts to repair damaged structures, these attempts could not prevent the city’s gradual decline.

Religious conflicts between Catholic and Donatist Christians also exacerbated the city’s troubles. Although Sabratha experienced a brief resurgence during the Byzantine period, especially following the Vandal occupation, it never regained its former glory. The Byzantines, under Emperor Justinian, undertook several construction projects, including a basilica with a splendid mosaic floor. Despite these efforts, the city was largely abandoned between the 7th and 9th centuries during the early Arab conquests, with most inhabitants migrating to Oea (Tripoli), which became the principal urban center in the region.

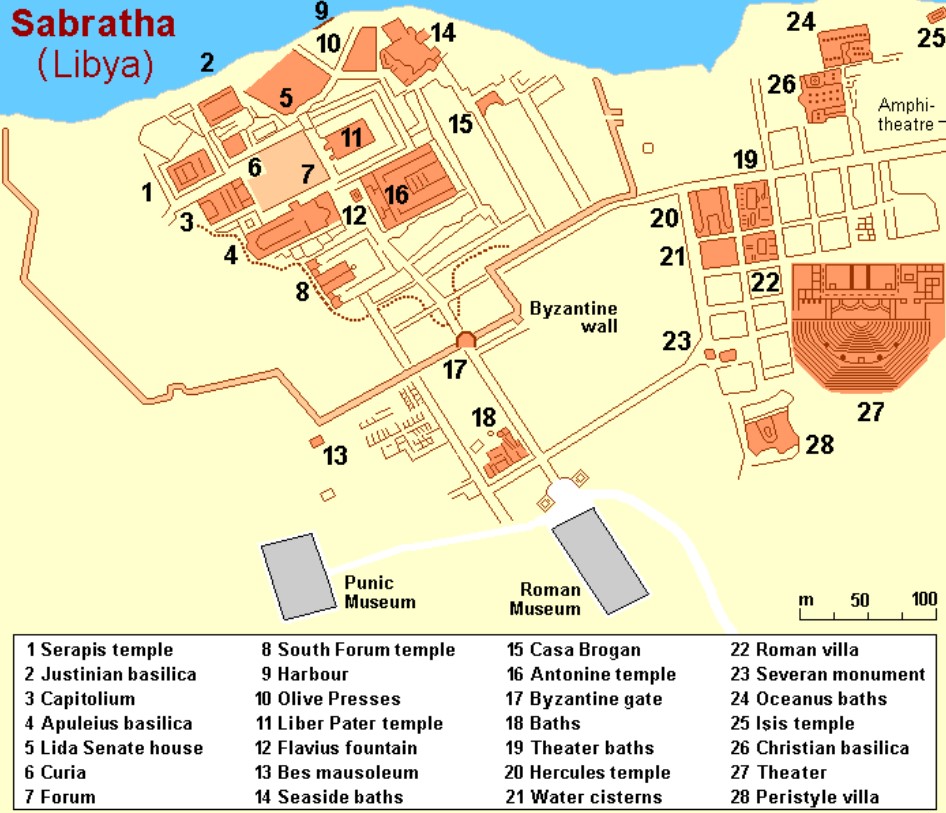

Map of Ancient Sabratha

Archaeological Discoveries and Monuments

Excavations in Sabratha have uncovered a wealth of monuments and residential quarters, shedding light on its rich architectural and cultural heritage.

The earliest Phoenician and Punic settlements were likely concentrated around the area later occupied by the forum and nearby structures. Evidence of these early layers includes ancient pottery fragments and pre-Roman structures made of stone and raw brick, uncovered through deep excavation in this area.

The irregular layout of Sabratha’s oldest neighborhoods persisted even during the Roman period, only partially adjusted by the construction of the forum and other civic buildings. Remnants of a Punic wall, dating back to the Carthaginian era, were identified along the northern boundary of the forum. These findings suggest that the settlement extended significantly during the Punic period, with a necropolis located approximately 300 meters south of the theater. The cemetery included various burial types, including chamber tombs with vertical access shafts, a style common in Punic and Punico-Roman contexts. Artifacts from these tombs, such as pottery and glassware, date to the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, underscoring the city’s long history.

Under Roman rule, Sabratha saw the construction of many grand structures, including the forum, basilica, temples, bathhouses (thermae), private homes (domus), an amphitheater, and a magnificent theater from the 2nd century CE. The city's layout and architecture display both traditional Roman elements and adaptations suited to the local environment.

One of the most significant monuments in Sabratha is the Roman theater, located in the eastern section of the city. Constructed sometime between the 2nd and 3rd centuries, this theater is one of the largest in Roman Africa and is noted for its architectural beauty. Its design includes a semicircular seating area, carefully positioned to face northward and shield spectators from the desert winds — a technique recommended by the Roman architect Vitruvius. The stage building features a stunning three-story façade adorned with marble columns, and the seating area is well-preserved, with space for approximately 5,000 spectators.

The Temple of Antoninus Pius in Ancient Sabratha

To the west, the forum area hosts several temples and monuments, including the Temple of Antoninus Pius and a Christian basilica built under Justinian. The nearby baths, located along the coastline, showcase mosaics with vibrant colors, which are well-preserved and visible today.

Mausoleum of Bes in Ancient Sabratha

In addition to the theater, several temples were dedicated to prominent deities, such as Liber Pater, Serapis, Hercules, and Isis. These temples, located in the eastern part of the city near the coast, reflect the religious diversity of Sabratha’s population. To the west, inside the Byzantine walls, lies the Mausoleum of Bes, a Punic-Hellenistic structure dating back to the 2nd century BCE. This mausoleum, similar in style to the Mausoleum of Massinissa in Thugga, Tunisia, was largely reconstructed by Libyan archaeologists after 1920.

A short distance from the site, about a kilometer west of the city center, stands the Roman amphitheater, built in the 2nd century CE. With seating for roughly 10,000 spectators, the amphitheater is relatively well-preserved, and the underground galleries used to release animals into the arena are still visible today.

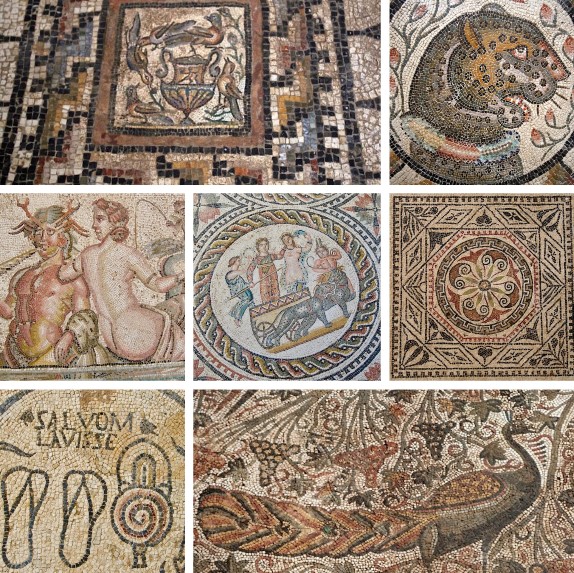

Some mosaics in Ancient Sabratha

Mosaics, Paintings, and Building Materials

Several neighborhoods in Sabratha have revealed Roman baths with intricate mosaics, some dating back to the reign of Justinian. Among the most famous is a Justinian-era basilica mosaic featuring large acanthus scrolls populated with birds. Other notable artworks include frescoes in residential homes, such as the 2nd-century paintings in the 'House of Leda' and the 'House of Ariadne', characterized by vibrant colors that contrast with the more subdued shading typical of Hellenistic art.

The Sabratans primarily used local sandstone, a soft and porous material that has suffered from significant erosion over the centuries. This sandstone, covered in a thick layer of plaster, formed the basis for many architectural elements, including columns and capitals. Although marble from other regions began to appear in the 2nd century, sandstone remained the dominant building material. This reliance on less durable materials has contributed to the rapid deterioration of Sabratha's monuments, necessitating continuous preservation efforts.

Last update: November 1, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE