Segesta, the most important of the Elymian cities

Segesta (Akeste or Eghesta for all Greek authors except Ptolemy) was the most important city of the Elymians, whose ruins are located on the slopes of Mount Barbaro, about 20 km from the coast.

The Elymians (in Greek, Elymoi, and in Latin, Elymi) were an ancient population inhabiting the westernmost tip of Sicily. Segesta was their most significant city. We do not know the exact date of its foundation, but evidence shows it was already inhabited in the 9th century BCE.

One strand of tradition held that the Elymians originated from Italy, but ancient writers narrated a Trojan origin for them.

According to the Greek historian Thucydides (Thucyd., VI, 2), the Trojan refugees, crossing the Mediterranean Sea, reached Sicily and founded Segesta. These refugees then took the name Elymians.

Virgil recounts that Aeneas, fleeing from Troy with his people, stopped in Sicily during his journey to Rome and founded the colony of Segesta in this area, where his father remained with a significant portion of the traveling companions.

Another tradition claims that Segesta was founded by Acestes (or Egestes), son of the Trojan Segesta. Her father, Hippotes or Phinodamus, had entrusted her to merchants to save her from the monster sent by Poseidon as revenge for Laomedon's failure to pay him. Taken to Sicily, Segesta, exhausted from wandering, rested by a river in the area and was impregnated by the river god Crimisus. From this union, , the city's first king and founder, was born. According to legend, Acestes hosted Aeneas and buried Anchises (Aeneid, 1550, V 718).

The language of the Elymians, documented by inscriptions scratched onto vases, belongs to the Indo-European family. Scholars widely agree it aligns with the Italic group rather than the Anatolian group.

The Elymians were often in conflict with Greek colonies and allied with the Carthaginians.

Approximate locations of the Elymians and their neighbors, the Sicani and the Sicels, in Sicily around 11th century BCE (before the arrival of the Phoenicians and the Greeks).

The Segestan Wars

Segesta and Selinunte were at war over boundary disputes from their very foundation. Segesta, heavily Hellenized in appearance and culture, played a leading role among Sicilian centers and in the Mediterranean basin. Its ongoing hostility with Selinunte involved even Athens and Carthage.

The first clash is narrated by Diodorus Siculus. It tells of the legendary Greek commander Pentathlus of Cnidus leading an attempt to colonize Western Sicily between 580-576 BCE, with Segesta emerging victorious.

After this the Siceli put the leadership in each case in the hands of the ablest man, but the Sicani quarrelled over the lordship and warred against each other during a long period of time. But many years later than these events, when the islands again were becoming steadily more destitute of inhabitants, certain men of Cnidus and Rhodes, being aggrieved at the harsh treatment they were receiving at the hands of the kings of Asia, resolved to send out a colony. Consequently, having chosen for their leader Pentathlus of Cnidus who traced his ancestry back to Hippotes, who was a descendant of Heracles in the course of the Fiftieth Olympiad, that in which Epitelidas of Sparta won the "stadion," these settlers, then, of the company of Pentathlus sailed to Sicily to the regions about Lilybaion, where they found the inhabitants of Egesta and of Selinus at war with one another.

And being persuaded by the men of Selinus to take their side in the war, they suffered heavy losses in the battle, Pentathlus himself being among those who fell. Consequently the survivors, since the men of Selinus had been defeated in the war, decided to return to their homes; and choosing for leaders Gorgus and Thestor and Epithersides, who were relatives of Pentathlus, they sailed off through the Tyrrhenian sea. But when they put in at Lipara and received a kindly reception, they were prevailed upon to make common cause with the inhabitants of Lipara in forming a single community there, since of the colony of Aeolus there remained only about five hundred men. At a later time, because they were being harassed by the Tyrrheni who were carrying on piracy on the sea, they fitted out a fleet, and divided themselves into two bodies, one of which took over the cultivation of the islands which they had made the common property of the community, whereas the other was to fight the pirates; their possessions also they made common property, and living according to the public mess system, they passed their lives in this communistic fashion for some time. - (Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, IX, 1-3)

Around 454 BCE, Segesta allied with Athens (Diodorus Siculus, XI, 86), allowing it to seek Athens' help on several occasions:

- Before 433 BCE, when Segesta allied with Ionian cities like Leontini to oppose Doric Syracuse

- In 427 BCE, due to Selinuntines' repeated boundary violations during Athens' first Sicilian expedition amidst the Peloponnesian War.

- In 416 BCE, when it was again at war with Selinunte, supported by Syracuse. Segesta deceived Athenian ambassadors into believing it had immense wealth to finance the war. Concerned about Doric Sicilian cities gaining power and disrupting the Peloponnesian War's balance, Athens organized a major expedition to Sicily from 415-413 BCE (Thucyd., VI, 6; Diod., XII, 82). However, the siege of Syracuse ended in a disastrous defeat for Athens.

As Selinunte and its allies intensified their efforts, Segesta sought Carthaginian aid (Diod., XIII, 43). This war ended with Selinunte's destruction, bringing Segesta entirely under Carthaginian influence.

In 397 BCE, besieged by Dionysius of Syracuse (Diod., XIV, 48), Segesta remained one of the few Sicilian cities loyal to Carthage.

At the top is displayed the geographical position of Syracuse and Carthage (the journey of Agathocles from Sicily to Africa lasted 6 nights and 7 days); while at the bottom, a golden gold depicting the tyrant.

In 307 BC, many Segestans were killed or sold into exploitation by Syracuse's tyrant Agathocles for failing to provide requested financial support.

Diodorus Siculus narrates that in 307 BC, the "Massacre of Segesta" occurred. Agathocles, despite numerous victories in Libya, returned to Sicily as Carthaginians besieged Syracuse. After being defeated in Libya and losing his sons, Agathocles fled back to Sicily. Encamped near Segesta, he demanded funds from the city's wealthy residents. When they refused, he subjected the city to immense suffering:

... the poorest inhabitants were dragged from the city and slaughtered by the Scamander River; the wealthier were cruelly tortured to disclose their wealth.

(Diodorus Siculus, XX, 71[3]).

Guided tour at sunset in the Valley of the Temples. The tourists are accompanied by gods, heroes, heroines and various mythological figures, statues that come alive, between reenactments of archaic rituals, dancing races, mischievous, litanies and verses drawn from works of famous authors of antiquity, mixed to the story of expert guides and archaeologists.

Agathocles executed others using catapults as if they were projectiles. He devised a torture device resembling the brazen 'Bull of Phalaris', involving a bronze table heated until the condemned perished. Pregnant women were crushed with stones to force premature births, while others set their homes ablaze in despair. Segesta was decimated, its population devastated, and its name changed to Diceopolis, "City of Justice" or "Punishment" (Diod., XX, 71).

In 276 BCE, the city surrendered to Pyrrhus, who became Sicily's ruler after Agathocles' death, later reverting to Punic control after Pyrrhus' departure.

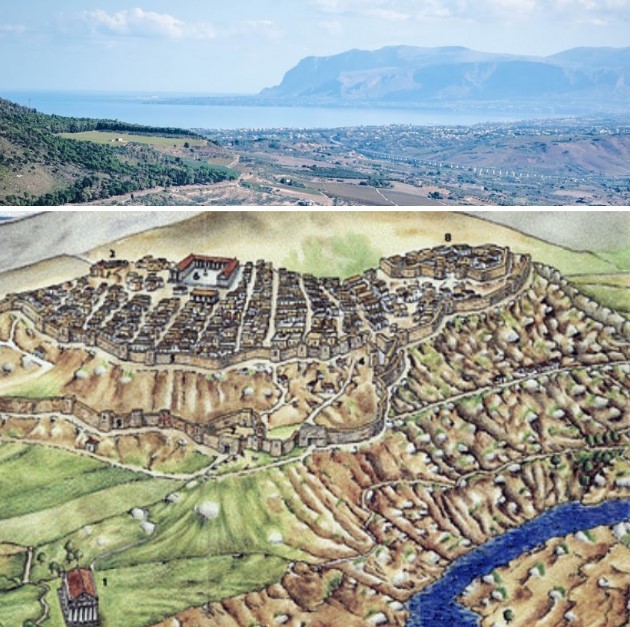

Graphical reconstruction of Segesta and current view of the sea from the ancient city.

Greco-Punic Wars

In 260 BCE, during the First Punic War (264-241 BCE), Segesta reclaimed its name and allied with Rome (Diod., XIII, 5). A strategic base for Roman forces, it endured a heavy Carthaginian siege.

Among the first Sicilian cities to side with Rome and due to its legendary Trojan ties, Rome declared it civitas libera et immunis (Cicero, Verr., III, 6, 13), exempting it from taxes, granting it vast territories (possibly including Eryx) and fostering prosperity.

Unfree laborers Revolts

Segesta played a significant role in the Sicilian unfree laborers revolts, led by Athenion (Diod., XXXIV, 5, 1). These revolts were brutally crushed by Rome in 99 BCE.

Segesta was destroyed by the Vandals in the 5th century and never rebuilt to its former grandeur.

The Archaeological Site of Segesta

Segesta occupied the summit of Mount Barbaro and featured two acropoleis separated by a saddle. The city was naturally defended by steep rock walls on the east and south sides, while the less protected side was fortified in the Classical era with a wall equipped with monumental gates. This was later replaced, during the early Imperial period, by a second line of walls built at a higher elevation.

Outside the double wall, along the ancient access roads to the city, two important sacred sites can be found: the Doric-style temple (late 5th century BCE) and the sanctuary in the Mango district (6th - 5th centuries BCE).

A Hellenistic necropolis has also been identified outside the walls.

Between the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, Segesta was completely redesigned following the model of the great cities of Asia Minor, adopting a highly scenic appearance.

The urban layout of Segesta is still under investigation. Based on aerial photographs and a few visible remains, it has been suggested that the city had an orthogonal grid of the Hippodamian type. Probable road layouts, the agora area, and some residential structures have been identified.

The unfinished temple of Segesta

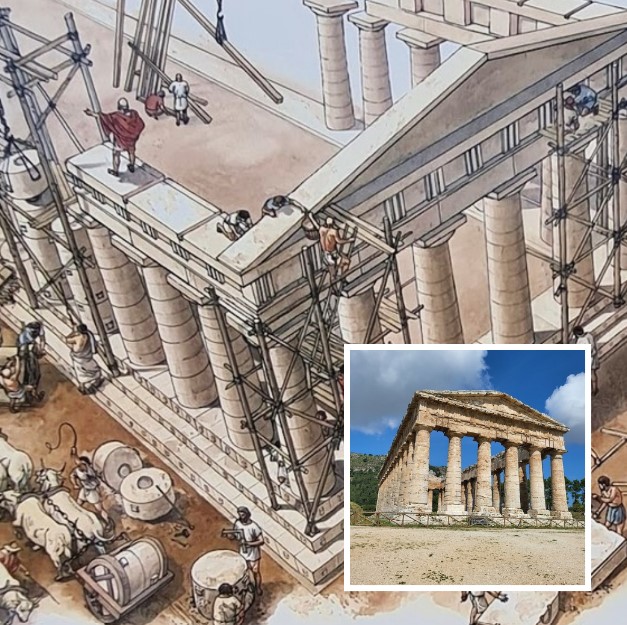

The temple is a Greek-Siceliot peripteral structure in Doric style, featuring a 6x14 column layout, and remains unfinished. After the colonnade was erected, construction (which began around 420 BC) was interrupted, most likely in 409 BCE, when Segesta fell under Carthaginian rule.

The cella, of which no visible surface traces remain today, had been planned and at least partially constructed, as evidenced by sections of the foundations uncovered during archaeological excavations.

The rough surfaces on the steps, which were typically smoothed only during the finishing phase, attest to the building's incomplete state. In its overall proportions and technical and stylistic features (capitals, cornices, corner contraction, curvature of horizontal lines), the temple closely follows the classical architectural models of Greek cities in Sicily, especially nearby Selinunte.

Certain distinctive features (palm decorations on the ceiling of corner cornices, mouldings of the pediment) and the proportions of the architectural elements also indicate a good understanding of contemporary Attic architecture.

No information is available about the cult or the altar associated with the temple. However, the modest remains of a simple sacred building discovered during excavations at the center of the temple suggest the existence of a pre-existing place of worship.

Agora

Starting from the second half of the 2nd century BC, numerous public monuments were built on the northern acropolis of Mount Barbaro, including the agora, the bouleuterion, the gymnasium, the theater, and almost certainly a temple.

The Theatre of Segesta

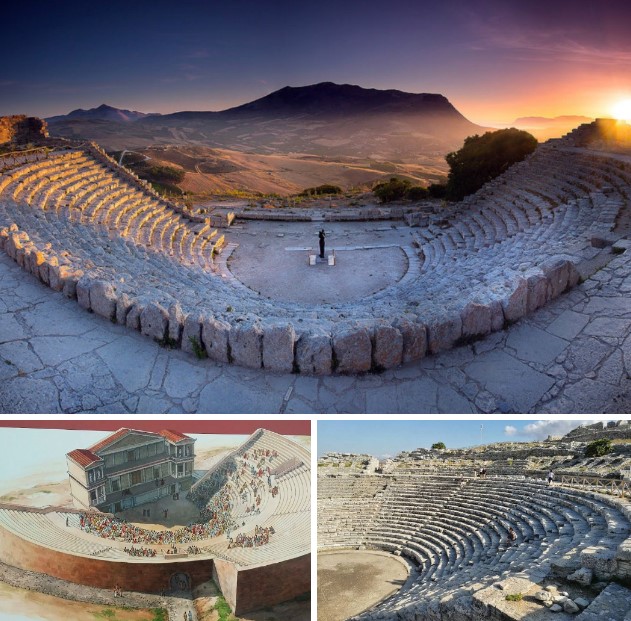

The theater, built in local limestone, was accessed via a wide paved road. It features the typical forms of Greek architecture, although, unlike these, the cavea, with seating for spectators, was entirely constructed and supported by a massive retaining wall (analemma).

The cavea, which could accommodate about 4,000 people, is divided horizontally by a wide corridor (diazoma) bordered by seats with backrests, and vertically by six staircases forming seven wedges (kerkides) of varying sizes.

A well and a water reservoir preserved in the western part of the analemma wall likely served the needs of both the audience and the actors.

The orchestra was accessed through lateral entrances (parodoi). A few rows of blocks allow the reconstruction of the plan of the skene, a two-story building in Doric and Ionic styles with two projecting wings (paraskenia) adorned with satyrs sculpted in high relief.

During the early Imperial Roman period, the theater underwent transformations: the orchestra space was expanded by removing a row of seats, and the stage front was enlarged.

Last update: November 29, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: