Uruk the first city

Between the 4th and 1st millennia BCE, the first great civilizations of the Mediterranean area flourished in Mesopotamia. During this same period and in the same region, the use of bronze weapons and tools spread, a technological advancement so significant that this era is known as the Bronze Age.

It is believed that the name "Iraq" may originate from Uruk (modern-day Warka). It was the oldest settlement and the cradle of Sumerian civilization. Around 4000 BCE, it grew from a simple village into a true city. Its geographical location was crucial for its development, as it was situated in southern Mesopotamia near the delta of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, which emptied into the Persian Gulf. The gradual domestication of native cereals from the foothills of the Zagros Mountains, combined with extensive irrigation techniques, allowed the region to support a wide variety of edible vegetation. This domestication and the proximity to rivers enabled Uruk to become the largest Sumerian settlement relatively easily.

The agricultural surplus of Uruk facilitated processes such as trade, job specialization, and the evolution of writing. At its peak, the city reached a population of 75,000 inhabitants, with a walled area of 6 square kilometers. For comparison, medieval Florence, one of Europe's largest cities during Dante's time, had a walled area of only 4.3 square kilometers. Ancient Near Eastern cities were relatively large compared to the overall population of the ancient world, which was much less dense than today; it is estimated that the earliest Sumerian cities already had over 10,000 inhabitants each.

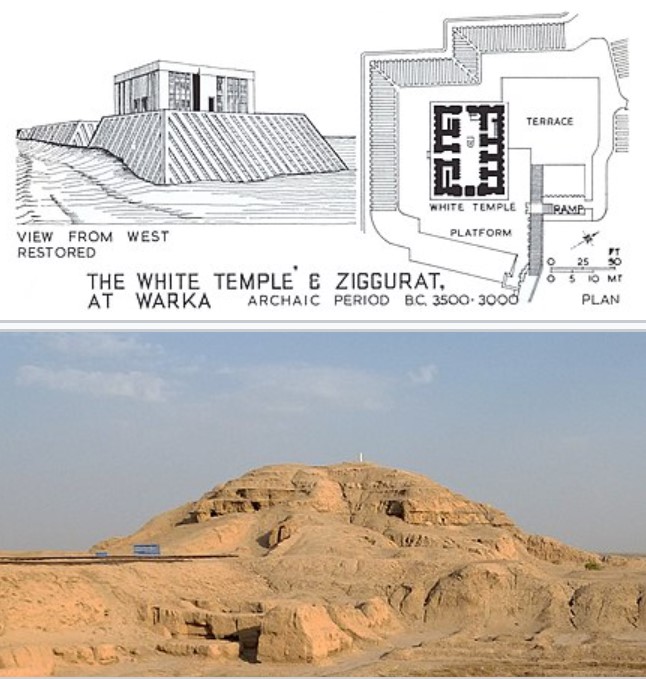

Anu / White Temple ziggurat at Uruk. The original pyramidal structure, the "Anu Ziggurat" dates to around 4000 BC, and the White Temple was built on top of it circa 3500–3000 BCE.

Uruk's development centered around monumental buildings, including temple complexes, the palace, and administrative buildings. The architecture was grand: the vast and harmonious spaces of the temples, courts, and palaces were adorned with refined decorations that broke up the high walls with projections and niches. Beautiful mosaics made of baked clay and stone decorated the walls, creating vibrant geometric patterns.

It's important to note that raw brick architecture has a millennia-long tradition and is not exclusive to Mesopotamia. It is found in all regions of the world with similar environmental conditions, such as Syria, Anatolia, Egypt, Palestine, Morocco, Yemen, and others. This construction technique has several advantages:

- The raw materials (earth and water) are widely available and very low-cost.

- It does not require specialized labor to work with it.

- Clay is an excellent insulator, keeping interiors cool in summer and warm in winter.

The only drawback is that it requires constant maintenance, as wind and rain gradually erode the clay. Uruk was also home to the god Anu, who had a grand temple there, the remains of which have been uncovered.

In those times, gods were often depicted in human form. An example of this is the so-called "Lady of Uruk," also known as the Warka Mask, a carved marble female face dating to 3200-3300 BCE, likely representing the goddess Inanna, and one of the oldest known depictions of the human face.

According to the Sumerians, civilization was created by the god Enki, the god of freshwater, who enabled the irrigation of the land. Enki, who was worshiped in a rural temple, passed on his gifts to the protective goddess of Uruk, Inanna. This myth symbolizes both the invention of agriculture and the birth of cities, asserting their dominance over the Sumerian landscape.

The myths of Mesopotamian gods often reflect, in a transformed way, the events of early history, particularly what we call the "Neolithic Revolution," as discussed in the introductory section on prehistory. Historical events following the invention of writing are also mirrored in these divine myths.

From the earliest historical period of Uruk, significant tablets with early forms of writing, almost pictographic in nature, have been discovered. Writing was invented independently in Mesopotamia and Egypt. According to a Sumerian poem, the goddess Inanna received the gift of writing from Enki, the creator god of civilization, and bestowed it upon the city of Uruk. Another poem attributes the invention of writing to a mythical king of Uruk, who wanted to send a message so long and complex that he couldn’t trust it to the memory of a messenger.

In reality, among the Sumerians, the idea of written records emerged alongside the growth of cities, primarily for the service of kings and temple priests, who collected taxes, stored provisions, owned vast herds of livestock, and eventually found it essential to keep accounts. Initially, small clay objects of various shapes were used, marked with notches and symbols, which were kept by threading them on a cord or placing them in clay jars. Later, in the mid-4th millennium BCE, impressions of these objects were made on wet clay tablets, which were then baked and solidified into terracotta for archiving. This process led to the development of seals, and from there, it was a short step to start inscribing symbols directly onto clay tablets using a pointed stylus, which began around 3300 BCE.

Houses in Uruk

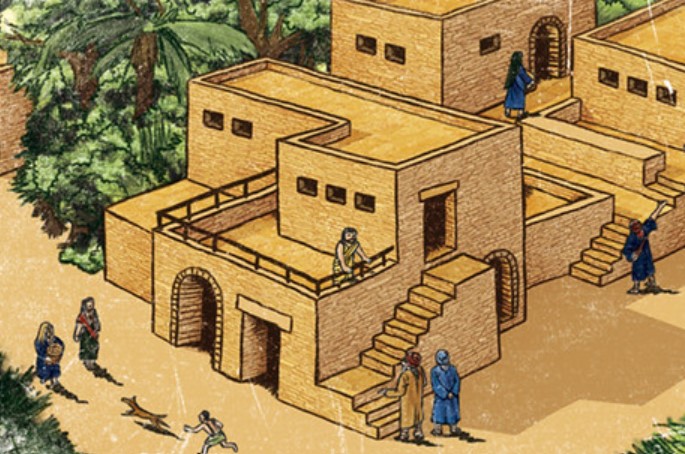

Houses in Uruk were typically one or two stories high and built around an inner courtyard. Different craftspeople formed separate neighborhoods, and the entire city was crisscrossed by a network of canals that connected it to the Euphrates' river traffic. These houses were mainly constructed with raw bricks made of clay, mud, and sand, mixed with straw and left to dry in the sun. Since Mesopotamia lacked timber and stone, other building materials were imported from Syria and Persia.

According to legend, Uruk's walls were built by King Gilgamesh: a circuit of 9 kilometers with 900 towers. Initially, the city was not fortified, but as rivalries among kings grew, every city began to defend itself with walls and towers. Many rural villages, impossible to defend, were abandoned, and most farmers likely lived within the city's protection.

Gilgamesh was a mythical figure, unlike the very real and powerful King Lugalzagesi. Gilgamesh was the hero of the oldest cycle of epic poems in human history, which recounts his battles with various monsters and his quest for immortality.

Uruk also held another distinction: the oldest code of laws in human history survived to the present day. It was written by Ur-Nammu, king of Uruk, around 2100 BCE, and included 57 chapters. In its prologue, the king claimed to have published it

to establish equity in the land, banish curses, violence, and disputes, and he also boasted of protecting the weak: the orphan was not delivered to the rich; the widow was not delivered to the powerful; the man of one shekel [11 grams of silver] was not delivered to the man of a mina [equal to 60 shekels].

The publication of codes by kings served to display their authority, show the people that they cared for their needs, and combat social disintegration.

Archaeological excavations have revealed another city to the north, Hamoukar, on the upper Tigris. The city was conquered by its rivals, the people of Uruk, around 3500 BCE, which is considered to be the first battle in history.

Around 2000 BCE, Uruk lost its dominant position in the conflict between Babylon and Elam. During Hammurabi's reign (1792-1750 BCE), drought continued to ravage southern Mesopotamia, and the region that once housed Ur and Uruk gradually became depopulated. The city was abandoned shortly before or after the Islamic conquest of 633-638 CE.

Last update: October 8, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: